From the late reproductive stage to the final menstrual period, the female body goes through a great deal of change. The spikes in estrogen during menopause cause an unpredictability that makes the transition particularly difficult. Unlike the pattern of stocking up on tampons and Advil every 28 days, women are thrown for a loop when their hormones become erratic. Dr. Jan Shifren and Dr. Nancy Woods go in-depth about memory function, feeling unstable, and what women need to be aware of during menopause.

Show notes + Transcript

Emily: I’m Emily Kumler and this is Empowered health. This week on Empowered Health we’re going to have our third part series on menopause and this week we’re really focusing on menopause as a physical and sort of emotional transition into the second phase of life or some might say the third phase of life. This is significant because women are living longer and I think after you’ve had your kids or your reproductive period ends, there is this idea that you can sort of rethink about who you are and what you want to do. We’re going to talk to some experts, some of whom we’ve talked to in previous episodes. One is on hormone replacement therapy and what the controversy was around that and what the research indicates and the first episode was all about perimenopause and the late reproductive phase and then those sort of set us up to have a better understanding and a better conversation about what menopause actually is because now we know that there is this sort of differentiation.

Jan Shifren: My name is Dr. Jan Shifren and I am the Vincent Trustees professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive biology at Harvard medical school. I’m also the director of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Midlife Women’s health center.

Emily: And then this is sort of an oversimplified question, but in terms of calling this a transition, one of the things that I think is commonly confusing is this idea of why is this so disruptive? If you come through the other side and you, you’re okay, right? Or in some cases people say, like Gloria Steinem famously talks about how, you know, she’s better than ever having gone through menopause that like she feels a stability that she hadn’t felt, you know, since she was 11. And I think there’s something really interesting about the idea that like your body is going through this hormonal transition that will then end with, you know, less estrogen, which is what is causing the disruption. And yet when you get through it, you’re okay. Is it, is there a way of describing that that like your body has to learn again how to respond to life without estrogen or what is that?

Jan Shifren: You know, I think it’s important to realize that the transition, the reason it’s chaotic is that it’s not just low estrogen. It’s low estrogen one month or two and then high estrogen or normal estrogen the next month or two. So it’s really the unpredictability that makes the menopause transition, I think, so complex for many women. Once you’re menopausal, there are women who are going to continue to have hot flashes if they don’t take treatment for seven to ten years. So I’m thrilled that Gloria Steinem felt great, but there are a lot of menopausal women out there who are really symptomatic. And so it is important that even after the menopause transition, if you are menopausal and symptomatic with hot flashes and night sweats and sleep disruption and fatigue, they speak with their healthcare provider. And if you’re healthy and you’re within ten years of menopause or under age 60 the greatest likelihood is that hormone therapy may be a really good option for you. So just making it to menopause does not mean that all of a sudden all the symptoms go away. For some women, they can be really symptomatic even after they haven’t had a period for ten years. I mean for one year, which is the definition.

Emily: Right. But like let’s talk about somebody who’s 70 right, who’s gone through menopause on the other side of it, their body is now functioning in a way that is, you know, sort of regulated again and it’s this period of transition that’s the dysfunction or the dysregularity or the inconsistency as you’ve said, that it’s causing the distress. My question is more of like that distress is just because they’re such swings and so there’s not a homeostasis within the body that can sort of tolerate the changes. Is that correct?

Jan Shifren: I think that’s a fair way of saying it, Emily. I mean basically most of us do well, well we know what to expect from our bodies. And so the menopause transition, it can be really rough cause you don’t know what to expect and it’s hard to make a treatment decision because you feel really well and then all of a sudden you don’t and you make an appointment with your healthcare provider and then you’re feeling better again. So I think that’s what makes a transition so difficult. But to be fair, there are a lot of women who are menopausal, haven’t had a period for a year who are really miserable. They’re having hot flashes and night sweats and from most women they resolve relatively… They can resolve within months to a few years. But there are women who are still symptomatic seven to 10 years after menopause. So really it’s very individual and each woman really needs to work with their healthcare provider to make that best decision about what options will work for her.

Emily: The sort of perimenopause period is also something that’s hitting women at a younger age than it was 50 years ago. Is that accurate or is it just being studied more carefully now?

Jan Shifren: The age of menopause is typically 51 and that can be plus or minus five years easily. And that really has not changed in over 150 years since we’ve been monitoring it in the developed world, which is fascinating. What it really means is that menopause is kind of genetically programmed, whereas age of the first period, what we call menarche, I think everyone knows has become much earlier. We see that’s probably due to better nutrition or unfortunately on the other end, obesity, the age of menopause has stayed remarkably constant, and so it really is probably just genetically programmed.

Emily: because I feel like you hear a lot in women’s magazines and whatnot, that people are experiencing this at a younger age.

Jan Shifren: Emily, I think you’re right. It’s not that women are experiencing it younger. I see that there’s more awareness that perimenopausal symptoms start as early as 40 for many women and it could go on for 10 years and so that it is, it’s nice that there’s more out there in the public domain that as women start to experience a lot of changes even in their early forties that could be the beginning of the menopause transition, so I think there’s more awareness rather than that the age is earlier.

Emily: So listening to Dr. Shifren, I feel like is eye-opening because you think of this as sort of like a teetering off of estrogen and it’s not, right? It’s like this really volatile spikes in estrogen, and if you take that into account, then it totally explains why women feel so moody and unstable during this phase and why they feel like their body isn’t really their own. It turns out there’s a lot happening with the brain, so we know post-menopausal women face serious risks when it comes to bone health and also heart health, which we talked about in the previous episode with the mouse model. And next we’re going to talk a little bit about what is happening in the brain of a menopausal woman.

Nancy Woods: My name is Nancy Woods. I have been involved in studying women’s health since the early 1970s my initial preparation was in nursing. I earned a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in nursing. Then went on to earn a PhD in epidemiology. I was really stimulated to study women’s health in a period of time that was just pass the early stages of the second women’s movement in the US and during a very active period in the history of the popular health movement in this country. So those two things came together to really stimulate me to think about what women wanted to know about their health, what women needed to know about their health and how to help women find the information they needed.

Emily: I think that perspective is so interesting too because so many things are changing for women in the 70s and it kind of makes perfect sense that there all of a sudden was this realization or opportunity even for people to go a little bit deeper and dive into, from a medical perspective, like how are we different and what, where is the equality and all that kind of really important work. I’m sure that must have been a really exciting time.

Nancy Woods: I remember, in that period of time people asking me what I meant by women’s health and, wasn’t that the same as gynecology or obstetrics? And my response was, no, women are more than their reproductive organs and functions. We need to understand much better the consequences of being a woman for our health, both living in a gendered body in society, but also living with two x chromosomes and how that sets in motion a whole series of processes in the human body that differentiate us and some very important ways that affect our health.

Emily: I love to hear that. I feel like that’s exactly why we wanted to do this whole project because it feels like there are, you know, to assume that we’re the same in any way feels oversimplified, I guess to say the least.

Nancy Woods: Right.

Emily: So I think the next thing that’s really interesting is the idea of cognition, right? Because we know that there’s a connection between estrogen and brain function and we know that women often have sort of like both mood, you know, disruption when they go through perimenopause as well as depression. And that SSRIs are sometimes helpful for that. But we also know that women suffer a memory loss, right? And that women are much more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than men. Two-thirds of all Alzheimer’s cases in the United States are women. And so I sort of feel like you can talk a little bit about that work too. That would be great to sort of kick us into the perimenopause phase of life.

Nancy Woods: The early work that we did on memory was not actually giving women functional tests of can you remember 10 words and can you repeat them later on? If we ask you a second time, we actually ask women for their perspectives. Were they noticing that they were having difficulty with memory functioning? What we learned from that was the women described their symptoms as including fuzzy thinking and difficulty concentrating. Those were symptoms that they also found interfered with their ability to do their work, so in their employment and to sustain or be in relationships. And I think that was important because we would not necessarily have garnered that information had we just used functional measures because the changes, women perceived were very small. So when we look at women in midlife, going through the menopausal transition, we see the where now did I put my keys?

Nancy Woods: I thought I left them in the kitchen, but they’re not where I usually leave them as opposed to I can’t remember how to put my clothes on. And that’s a drastic difference in functioning. That types of problems that we saw women experiencing in the menopausal transition have been much more mild, I would say. So disruptive in that they interfere with one’s ability to work or to sustain a relationship, but they are not severe impairments. Some of the best work that has been done on this recently has been done with the participants in this one study, the study of women across the nation, which is a very large study, nearly 3000 women from six different sites in the US some of whom actually participated in what I’m calling the functional memory testing, where women would go through a battery of neuropsychological tests that are designed specifically to look at certain types of memory. And in those tests, it’s difficult to see change because one of the things that investigators have to pay attention to is that when we take a test, we learn from it. So if I take a test this year and I take the same test next year, which is a necessary thing, if I’m going to track progress over time, I will do better on that test next year because I will have learned from taking the test the first time around in these studies, there has needed to be attention to how women’s scores were changing over time. The changes during the menopausal transition are very modest. In addition, the changes are not declined, the changes are on average. Women do not improve as rapidly as they would have prior to their experiencing the menopausal transition. And the woman who’s really done probably some of the best work in that is Dr. Gold from UCLA. And I can send you some information from her work.

Emily: Well and so can you just explain like what does that mean to you? Like what’s the takeaway that like they’re, they’re not learning as quickly, but they probably haven’t had, like they didn’t have a baseline when they were 30 or something like that, right?

Nancy Woods: No. But probably now what we would expect is if they were tested at 30, 35, 40, 45 50, they would keep getting better scores over time. So the, the real change was that the scores didn’t improve quite so rapidly,

Emily: Which implies decline.

Nancy Woods: Not decline in terms of getting worse, but not getting better scores as quickly as one might expect. So it isn’t, “oh my gosh, this is the onset of dementia,” not at all. Instead, it was, there is a change going on in cognitive functioning that indicates that learning is not occurring as rapidly as it had earlier in the menopausal transition.

Emily: And so is that an estrogen drop link?

Nancy Woods: I think that we’re seeing some evidence of that now. There are some, there are some studies that are ongoing. One of the investigators whose work is really important in this area is a woman by the name of Miriam Weber, who has also worked with a woman by the name of Pauline Macki. Dr. Weber has done really important work with dementia, but she’s now back at younger women, women in mid-life and studying what is happening with women’s hormonal changes during mid-life, during the menopausal transition and early post-menopause and the consequence or the association really not the consequence because the study designs are such that we’re just describing what we see and not making.

Emily: associations.

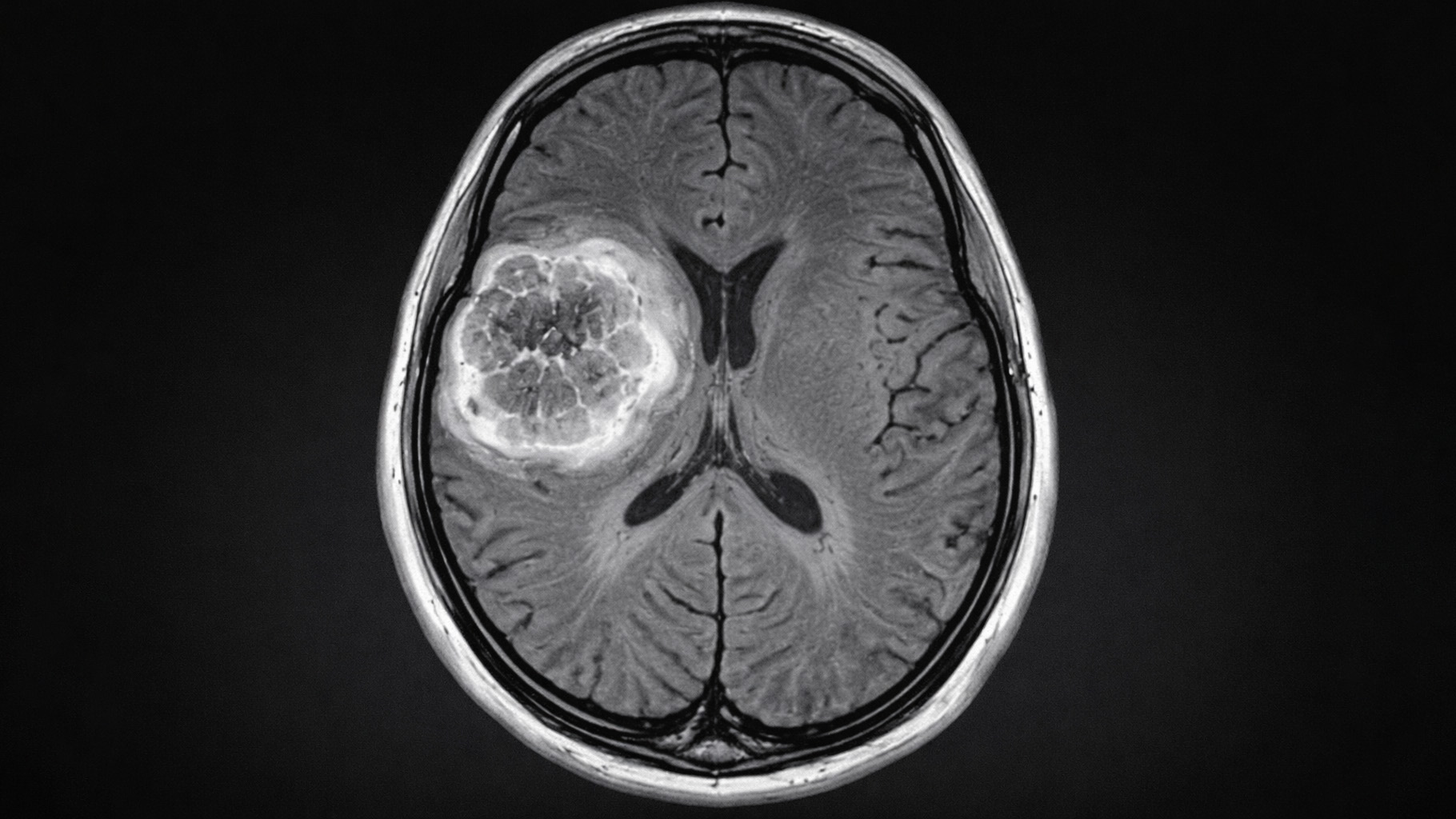

Nancy Woods: -inferences from them, which is a very important distinction. So what she is finding is that cognitive functioning in women changes over the course of the, of the mid-life. So there’s a particular area in women that seems to be related to hormonal change and that’s a verbal learning. So usually that’s tested by asking questions about naming things or memorizing words and verbal memory, how long you can hold those words in memory of somebody asks you 10 or 15 minutes later, “now, what were those four words I gave you to remember?” And then there’s also some changes that she’s seen in motor function. So that’s usually fine motor, like finger tapping is an exercise that is done. The other thing that she is seeing is that that the real change is not so much in the transition but post-menopause. So the women who are measured after menopause tend to do less well than women who are in the transition or even in the late reproductive stage. So those are the sorts of things that we’re learning. These are just very early kinds of investigations and I think the way that these studies are being done now are going to be able to engage women in doing tasks while they’re being studied with fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging. So brain imaging studies that actually measure areas of the brain that are stimulated, that are actually operational when women are asked to do certain tasks. I think that what I’m excited about is thinking about the changes that may be occurring that are so subtle that we don’t see a huge drop off in scores on these cognitive functioning tests. Because the changes are very subtle and they’re very gradual, so when you have a little bit of change, it’s hard to see the effect of changing hormones, but when you can look at now brain functioning in ways that allow you to say, oh, that is the Amygdala that stimulate it, or that is the hippocampus, it’s being stimulated.

Nancy Woods: You can begin to think more about, well, what are the mechanisms that are affected and how does estrogen really work? We have some ideas about that, but we don’t have the functional studies that would allow us to say, oh, when estrogen levels are changing, this happens. We have correlational evidence and some of the most interesting for women who are in this late reproductive stage, so where they not started having major changes in their menstrual cycles, but they’re having a sense that things are different. Sometimes they’re having sleep disturbances, they’re maybe having periods of anxiety. They may be having hot flashes, beginning to have hot flashes. These are periods before your cycles differ in length by a week or more, which is one of the markers that researchers now use for saying this is the early menopausal transition. So when you begin looking at these periods in a woman’s life where there’s not dramatic changes in menstrual cycles, but women will say, “you know, my cycles getting, my periods are getting closer together or I have less menstrual flow.”

Nancy Woods: They begin to notice some of these subtle changes and for some but not all women, there may also be changes in the symptoms they experience, so they may identify, “Oh, I’m waking up during the night and I can’t get back to sleep. I feel anxious, I feel hot.” They may not even have a vocabulary for talking about what they’re experiencing. What they may have happen is if they seek health care for this, the health professionals are likely to, and appropriately, think about, “well, how do I know if this is a menopausal transition?” Because measuring hormones doesn’t always answer that question. Estrogen levels during the menopausal transition are all over the place and follicle-stimulating hormone or FSH, which, which stimulates production of estrogen. Those levels are all over the place. These are pulsatile hormones. They don’t just sit still. They pulse. You don’t know whether you’ve the high level, the low level or somewhere in the middle of a woman’s average levels, so when this is going on, there’s a change beginning. Women may be sensitive to some of the changing endocrine levels. We do not yet have the kind of data to say, oh, that’s an estrogen-related change. We can suspect that. The closest work I’ve seen in this area has been some work that Ellen Freeman has done with Penn Ovarian aging study and what she found was that during what is called the late reproductive stage before women start the menopausal transition, the variation in estrogen levels is associated with symptoms women experience. In particular, she had looked at hot flashes and symptoms of depressed mood. Those symptoms tended to appear or to be more severe when women had a lot of variability, so meaning their hormone levels were up and down over time.

Emily: Well, and I think one of the things that’s so fascinating is this idea of sort of like symptoms clustering together. Right? And so somebody might think like, oh, I’m just depressed, or oh I’m just, I’m too hot. Like for some, you know, at the summer is particularly terrible. I’m hot all the time. You know, you don’t necessarily make the connection between all of these things. But I do think doing an fMRI will probably be revealing on so many levels because some of these basic questions could finally be answered, not just the memory stuff or the cognitive stuff, but also like where is the estrogen going first, right? Like how is it interacting with everything else and how is that changing over the stages of perimenopause or menopause? And I guess giving some credibility to the things that women have been saying for a long time as physiologically based rather than environmentally based. Right?

Nancy Woods: Yes. And I would say probably we always need to look at the combination of those things. So a woman’s symptom experiences are definitely related to what is happening in her body. We have not had much awareness aside from measurements of hormone levels about what is happening in the body. But we know that the reproductive hormones first of all, are very tightly controlled by the brain. So your estrogen levels are controlled in the hypothalamus of the brain, which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete FSH that stimulates the production of estrogen in ovarian follicles. So the brain is involved from the start. This isn’t just about ovarian function. So the brain has the ability to modulate ovarian function that opens the gate for having the influence of environment on ovarian function. Very important concept. So when we looked at women, for example, who were exposed to extreme stress and starvation in particular during times of war or conflict, those women stop their menstrual cycles.

Nancy Woods: And that is because the brain is capable of transducing information about the body being in a situation of very high stress to shut down reproduction because it would not be adaptive to reproduce during a period of starvation would not be adaptive for you know, for our species. So there’s some basic hard-waring that finally tunes the menstrual cycle and I think we’re just scratching the surface of some of that. And then when we look at menopause, that is a period of what a physiologist would call perturbation. You have a stimulus which is changing production of estrogen in the ovarian follicles that is setting in motion now changes in metabolism changes and sometimes mood changes in thermoregulation. So women as they go through the menopausal transition have much narrower what is called the thermoneutral zone. So that’s a zone of body temperature range between sweating, being really hot and shivering, being really cold, that range becomes much more narrow as a woman completes the menopausal transition.And that’s why women have hot flashes and then cold sweats sometimes within seconds of one another.

Emily: Delightful.

Nancy Woods: Yeah. Well, I mean there’s what we’re learning from neuroscience and the new methods of neuroscience is extremely important.

Emily: Is there any kind of like mirrored experience that happens during adolescence?

Nancy Woods: It’s interesting you mentioned that because there is a bit of a mirrored experience here. If you looked at some of the older studies done by a gentleman by the name of Treloar who had a women’s students at the University of Minnesota in a statistics class start keeping track of their menstrual cycles and then their daughter’s keeping track of theirs. What we learned from the Treloar data is that menopause is the mirror image of menarche in that monarchial girls start cycling but they’re not cycling regularly. Often they start out having periods that are two weeks long or six weeks long and then that rhythm matures and becomes refined and you know, varies right around an average of 28 days per cycle. And that persists throughout the reproductive years. But at the other end of the reproductive years, as women are entering the menopausal transition, that cyclic rhythm is less regular and eventually the cycles stop. So yes, there is a sort of a mirror.

Emily: but you know, you also think about adolescent girls being super distracted, right? Like I mean like ditzy, right? Is like what we always were called and it was, you know, kind of flighty or like you can’t remember where you were supposed to be or what you were supposed to do. And you know, people would say like, “oh, so-and-so has a crush on somebody.” Like they can’t think straight. But it’s like this kind of actually sounds in some ways like some of these symptoms,

Nancy Woods: You know, it would be very interesting to look at that. I don’t know that anybody’s looked at memory function in adolescents, but I can tell you having, you know, having raised an adolescent daughter, it is indeed a time of not being able to focus well.

Emily: Yeah. And anxiety, depression. I mean, I feel like a lot of these things seem very similar. Well there you go. Some new research cause you don’t have enough on your plate.

Nancy Woods: Well, I think probably I will leave that to somebody who will have the expertise on adolescence. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve found midlife and then even older age has consumed most of my energy these days.

Emily: Will you talk a little bit about the work that you’ve done as far as staging and why that’s so significant in terms of sort of an understanding of the, I guess, progression of menopause and then post-menopause?

Nancy Woods: Actually, one of my collaborators, Ellen Mitchell was a nurse practitioner and had started a very unusual practice back in the 1970’s that had a special focus on women and she became a magnet for women in the community who needed help related to the menstrual cycle, PMS, menopause, menopause-related symptoms. In the early days of our menopause research was needing to know more about the progression of changes that women were going through. And one of the things that we did with the Seattle Midlife Study was to engage, we invited women to come to advisory committee meetings where those who are participating in the study came in and we told them a bit about what we were finding. And then we gave them time to talk with us. And in our interviews we always ask, is there something that I should have asked you that I didn’t, you know, or is there anything else you’d like to come in on? When we asked women, what do you really hope to learn about menopause as a result of participating in this study? The majority of them said, we want to know when we’ll be done with us. Meaning when they would have their last period, usually for women who were having symptoms, when will I be done having these symptoms that are bothering me right now?

Emily: When will I feel better, essentially.

Nancy Woods: Yes, right! We really took our lead from the women and doing the work on staging. We were attempting to use menstrual calendars, so we had women keep a menstrual calendar, which is like an index card that had everyday of the year on it. And if you know you were having a bleed, if you were bleeding, you put a B in a little box for that day. Or if you were spotting, you put an “S” or you know, you were not having any menstrual flow, you left it blank and then on the back you could write little notes about things that you thought might’ve been influenced your cycle that month. We started out with 500 women in this study. You can imagine all the cards that we had because some of these women were enrolled in our study for 26 years.

Emily: Wow.

Nancy Woods: Early on though, we really got into thinking about staging and Ellen was really the driver of this and after just studying these cards and looking at changes that happened in cycle length and other characteristics and then looking at interview questions we had asked, she originally led the work, in our study to propose that women experience some changes in a stage-wide progression. She had identified originally that women noted shortening of their cycles and less menstrual flow. Then there came another stage where the women’s cycles varied a much as a week from one and then another stage where women just started skipping periods. So they might go for two or three months with no menses and then have another menstrual period. We wrote about that. Ellen led that paper back in the year 2000. One of her colleagues at University of Washington was a physician who studied infertility. He was also very concerned about staging, but what he was doing, because he was doing in vitro fertilization in his, he was actually visualizing the ovary and counting follicles. So we got together to talk about how we were thinking about staging the menopausal transition and the result of that was that Michael Soules really worked with us. He was the person who convinced the National Institute on Aging that we should have the first STRAW conference.

Emily: Can you talk a little bit about what he saw in terms of the follicle growth?

Nancy Woods: What he was looking at was follicle counts, so how many of follicles were remaining in the ovary, how many developed. You know with each wave ovarian follicles tend to develop in groups over time so that there’s an almost constant group that is developing, but towards the end of the menstrual cycle years you can notice or you can visualize that fewer follicles are, they call it recruited for this particular cycle.

Emily: Which means there’s a lesser chance of getting pregnant?

Nancy Woods: Yes, that is definitely related to fertility and very important for a woman who’s undergoing in vitro fertilization, who wants to use her own ova for in vitro fertilization to know that the chances are either very good or very limited that she might be able to become pregnant using in vitro fertilization.

Emily: Will you talk a little bit about the STRAW recommendations and like why that’s sort of become a standard?

Nancy Woods: The real important problem for STRAW to solve was that the literature, so the scientific publications about women and menopause use two time periods- pre-menopause and post-menopause. So pre-menopause was theoretically any time between an adolescence monarchial onset and the final menstrual period and post-menopause was anytime after the final menstrual period. And yet we knew that there were changes in fertility occurring across that pre-menopause period of time in a woman’s life, but no one had really tracked over the reproductive years what was happening and no one had really put together, well, here’s what happens in adolescence- cycles that mirror image, you were talking about cycles, become more regular during the menopausal transition cycles become less regular. That had not been seen as a lifespan process. We had looked at chunks of the life span rather than saying, Whoa, this is pretty interesting. This is a lifespan process and we really need to understand, you know, not only what’s getting it started, but you know what happens at the other end of the reproductive lifespan.

Nancy Woods: Oh, definitely. After, yeah. You know, doing studies that look at what’s called early post-menopause versus later post-menopause and realizing that, well, we don’t really know very much about what happens during the first five years after the final menstrual period. So that work is coming to be now with um, data from studies like Swan.

Emily: Are there any results from that that you feel like are

Nancy Woods: One of the assumptions has been that women stop their menses and then immediately go to a new what’s called the steady state. When you think about endocrine production as a result of paying attention now to the early post-menopause, there is increasing understanding of the role of conversion of androgens to estrogens and also the realization of the importance of the balance of Androgens to estrogens in the post-menopause. One area where this is very important is heart disease, cardiovascular disease in women. Studies that are looking at the post-menopause are beginning to tell us that there is consequence of antigen levels during this period of the early post-menopause.

Emily: And can you just give us a little background on what androgen levels, why they’re important, what do androgens do?

Nancy Woods: An androgenic profile in women is important because of its relationship with some of the heart disease risk factors, cardiovascular disease, risk factors. Women who have a more androgenic profile, meaning a higher ratio of Androgens to Estrogens, they may have lipid patterns that are more likely to place them at risk for heart disease. So higher levels of low density lipoproteins is one example.

Emily: And how does that change after menopause? Does the androgen actually go up or is the ratio change? Because the estrogen

Nancy Woods: That is a very perceptive question. The androgen levels do not tend to increase. They tend to remain rather static. And we’ve seen this on our own research, but what changes is the ratio of estrogen to androgen or androgen to estrogen, if you want to put it that way. Because as estrogen levels are decreasing, that change happens predominantly, we know now, in the last year before a woman’s last menses and then within a year to two after the last menstrual period, estrogen levels tend to stabilize. At a lower level as the amount of androgen or the ratio of androgen to estrogen becomes higher. That is a result of the drop in estrogen levels.

Emily: I’m so excited that we got to share those three episodes with you all looking at the late reproductive phase and perimenopause, which is clearly not well understood enough. Although I think we did get a good handle on the fact that your hormones start changing before your periods start changing and then that can already sort of set the stage to make you feel a little bit nuts. Things are changing, but everybody’s asking you if your periods are regular and you’re saying yes, which is probably where I am. I feel like this is just to be personal for a second, like it is a big deal when you start to feel like things are changing in your body and you can’t identify why or what. These episodes have been really informative for me personally because I feel like they kind of give you a framework for like, okay, this is going to happen first. Then this. Then this. Focusing specifically on the menopause transition and what that does. I think the brain stuff is so important because we know as we covered Alzheimer’s in that great episode sort of around the time that we launched last spring, we know that Alzheimer’s affects women much more than it does men– two thirds of all Alzheimer’s patients are women– but we also know that women are more likely to be the caretakers of Alzheimer’s. And I think with dementia very much on the female brain as it should be. It’s also really important to separate the fact that these hormonal changes that are affecting you that are enormous, will also have an impact on your cognitive abilities that you don’t feel like this is some sort of really dangerous thing. I think the more information we have, the more we can sort of acknowledge what’s normal and what’s not. Next week, I’m really excited to talk to the famous anthropologist Kristen Hawkes who is well known for coming up with the grandmother hypothesis, which is really looking at what point of women’s lives or why post-menopausal women are essential in societies. This is also really important because I think a lot of the value that we place on women has to do with our reproductive abilities. Certainly we see this in a lot of religious tradition, right? That like the point of being a woman or the value in a woman is your reproductive value and I think there’s so much more to our ability to contribute than just having kids and this grandmother hypothesis certainly features a sort of maternal matriarchal side, but it also looks at how women really are key to functioning societies. I’m excited to share that with you and I feel like that’s a really positive way to wrap up. This menopause stuff is hard and there’s a lot of stuff that is grueling and uncomfortable and knowing that it’s normal should help a little, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that there’s a lot of discomfort involved. I think when we get through to the other side, we become more key members of society for a number of different reasons, which we’ll get into next week. That also should help us all feel like, okay, this is great. We’re going to get to a point where we’re going to be stable. We’re not going to feel at the whim of our hormonal hot flashes and insomnia and skin problems and all the other things that we’ve heard about on these episodes as normal parts of this transition, which again, like I know this isn’t researched well, but it feels very much akin to puberty. So like you see somebody go through puberty and their skin is awful and they’re crying and hyper and you know, ditzy and all of these things. It seems like that’s sort of similar to menopause in a lot of ways. Knowing that helps me. I hope it helps you too. I hope you join me next week. Don’t forget to share these things with all of the women in your lives. We’re so thrilled that the audience is growing and we just can’t wait to help more women feel like they’ve got some power over their own health.I’m Emily Kumler and that was Empowered Health. Thanks for joining us. Don’t forget to check out our website at empoweredhealthshow.com for all the show notes, links to everything that was mentioned in the episode, as well as a chance to sign up for our newsletter and get some extra fun tidbits. See you next week.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

How a Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Naturally Activates the Same Pathways

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life