By Greg Glassman

This article, by BSI’s co-founder, was originally published in The CrossFit Journal. While Greg Glassman no longer owns CrossFit Inc., his writings and ideas revolutionized the world of fitness, and are reproduced here.

Coach Glassman named his training methodology ‘CrossFit,’ which became a trademarked term owned by CrossFit Inc. In order to preserve his writings in their original form, references to ‘CrossFit’ remain in this article.

Download a pdf of the original article HERE.

The King of All Exercises

Were it not for the snatch, the clean would have but laughable challenges to the title “King of All Exercises.” Oddly, we start our examination of the clean with mention of the snatch, as many of the superlatives attributed to the clean apply equally to the snatch. Clearing the air early with admission of the snatch’s peer status, we can speak more freely of the clean’s unrivaled qualities and need not repeatedly suggest the snatch’s possible exception to the clean’s peerless qualities.

Mechanics

The clean is a pure bit of functionality. The clean is simply pulling a load from the ground to the shoulders where frequently the object is being readied for lifting overhead. With the clean we take ourselves from standing over an object pulling it, to under it and supporting. (Compare this to the muscle-up where we take ourselves from under an object to supporting ourselves over it.)

In its finest expression the clean is a process by which the hips and legs launch a weight upward from the ground to about bellybutton height and then retreat under the weight with blinding speed to catch it before it has had the time to become a runaway train. The movement finishes with the hips and legs again working by squatting the weight up to full extension.

The speed and force with which the clean (and, yes, the snatch) drives loads give it developmental properties that other weight training movements cannot match. Deadlifts, squats, and bench presses will never approximate the speed and force and consequently the power required of a clean at larger loads. For this simple reason, while these are important movements, they are not the clean’s peers. Power is that important.

Developmental Qualities

The clean builds immense strength and power but this is only the more obvious part of the clean’s story. (This complex movement actually contains within itself two princely exercises – the deadlift and squat.) The clean is unique among weight training exercises in that it demands extraordinary athleticism beyond strength and power.

Experience coaching the clean will show that a lack of sufficient speed and flexibility are common impediments to learning the clean and that refinements in coordination, accuracy, and balance are the biggest obstacles of all.

The clean requires and develops enormous strength, flexibility, power, speed, accuracy, agility, coordination, and balance. The movement is as complex and nuanced as any movement in sport and can only be improved, never fully mastered.

At high reps, especially when fused with the push-jerk, the clean becomes a powerful tool for developing vitally important functional cardiorespiratory endurance and stamina.

There’s no part of your physical development that can’t be positively impacted by developing and improving your clean. The benefits to strength, flexibility, power, speed, accuracy, agility, coordination, and balance are directly proportionate to the load you can clean, and the benefits to your cardiorespiratory endurance and stamina are directly proportionate to the reps and load you can clean.

Application

The clean is as complete as an exercise can be, trains for super useful core to extremity motor recruitment patterns, and trains and conditions the body to apply large and sudden forces. It is “golf swing” or “baseball pitch” complex yet accessible to all who want to learn it.

Fortunately, you need not develop marked technical proficiency at the clean to benefit from its broad and potent athletic offering. In fact, errors in the clean’s execution may actually increase many of the demands of the movement at any given load, so that the more trouble you have developing a good clean the more benefit practicing and training it deliver.

Finally, the clean is a gateway exercise to the clean and jerk – one of the two Olympic lifts. The clean and jerk continues the clean’s journey from ground to shoulders with a second, powerful, whole body movement, the jerk, which sends the load overhead.

It is the combined movements, the clean and jerk, that at high-rep protocols simultaneously improve all ten general physical skills associated with physical training. Learning and working toward mastery of the clean is well justified by this application alone.

Setup and Preparation

Ideally you’d like to acquire a training bar and plates to learn the clean. The rig in the photo above is a fifteen pound “Alumalite” bar and five-pound training plates from Bigger Faster Stronger. The entire setup comes in at only twenty-five pounds.

It is all too common for beginners to practice with too much weight. Typically, when learning the clean the lighter weight seems to fly around erratically. In an attempt to control the movement, the athlete often wants to pile weight on the bar. All this accomplishes is to mute the effect of some of the errant movement, which serves only to mask errors in technique.

If you cannot perform the movement consistently and properly empty-handed or with a broomstick, your progress will come to an early screeching halt with weight. When that happens, your faults can only be diagnosed and corrected back at training loads, which is tantamount to starting over. Don’t waste your time by being in a hurry to lift large loads.

If the training bar and plates are out of your budget, you can make a training rig from PVC pipe and plywood. World Class Coaching’s videotape on the clean, “The World’s Most Powerful Lift,” features homemade lightweight training bars and plates.

Taping and Chalking

Taping the wrists can help with the discomfort in the racked position. The thumb also can be taped to keep the skin on it while using the hook grip. Use cloth athletic tape.

Chalk up with gymnastics and weightlifting chalk (magnesium carbonate) available from most sporting goods stores.

Hook Grip

The hook grip will greatly add to your lifting capacity. Though initially uncomfortable, if not painful, with practice the hook grip will feel perfectly natural.

Push your hands down hard on the bar and then reach around the thumb, with the index, middle, and ring finger trapping it against the bar. The pinkie finger, unable to reach over the thumb stays wrapped around the bar.

Depending on the size of your hand, you may or may not be able to get your ring finger around the thumb.

With a load, the bar does not stay in the hand but hangs from the fingers. The hook grip may eventually increase your clean by 50 percent or more!

Stance and Hand Placement

The starting stance for the clean places the legs and feet directly under the hips. This stance is slightly narrower than a squatting stance.

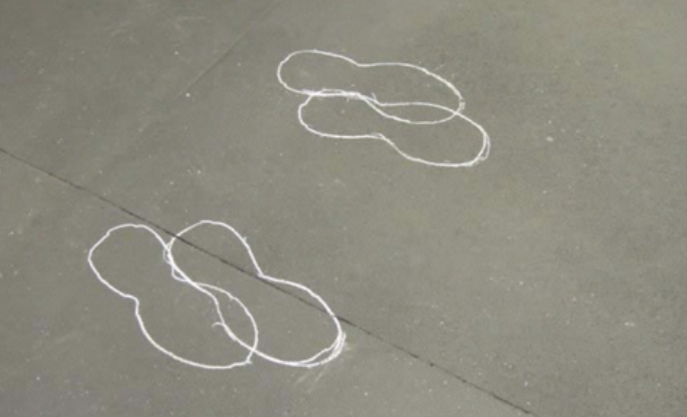

The chalk outlines in the photo at right show foot outlines of positions for both the starting stance and the “catching” or squatting stance. The starting stance is forward and narrower than the catching stance.

The hand position is just wide enough to keep the arms from interfering with the legs while pulling from the ground.

Ultimately your hand position will be determined by adjusting the grip so that the bar hits the explosion point where you’ve maximum capacity for hip and leg extension. More on this later.

Dave Leys, right, is in the starting stance. His feet are in the inside chalk outlines seen above right. When he drops under, he’ll land in the outer, rearward outlines.

The Rack

Notice in the picture to the right that the weight is sitting squarely on Dave’s chest and shoulders with his elbows pointing forward. This posture, called “racked,” is critical to weightlifting and demands and improves wrist and shoulder flexibility.

Practice the rack position with a moderate load on a squat rack. Reach out for the bar, pushing the shoulders and chest up and out, and then step under the bar and rest it in the channel formed by the chest and shoulders. The grip is loose, with several fingers possibly coming off the bar; that’s O.K. The hands are only babysitting the bar.

With the bar racked on the shoulders, stand up to lift it from the squat rack several inches, exposing the shoulders, chest, and wrists to the posture.

With regular practice anyone can learn to “rack” the bar and even arrive at acceptable levels of comfort with the position. Without this technique your clean’s development will be unnecessarily and dramatically limited.

Dumping

When a lift goes bad, and it happens regularly, you need to be able to dump the bar. Convince yourself by demonstrating that you can bail out from both the bottom and at the top.

From the bottom, spread the knees and push the bar forward letting it fall to the floor. Keep your hands close to the bar to control its descent.

Technique: The Liftoff

The liftoff begins essentially as a deadlift. The bar sits directly above the foot. The shoulders are slightly in front of the bar.

There’s nothing relaxed about the starting position. The chest is up and inflated; the lats and triceps are dug tightly into one another.

The arms are locked with the inside of the elbows facing one another. The hands, in the hook grip, may be turned a bit inward, just slightly flexing the wrists.

Try to keep the plane of the chest as upright as possible and your shoulders pinned back.

As the bar rises, the general direction of the bar is up and slightly back. By the time the bar reaches the knees, the shins have come to vertical, and the athlete’s weight has shifted from mid foot to the heels.

The arms are not pulling at all. Think of them as straps. The torso’s angle of inclination remains constant until the bar crosses the knee.

Technique: The Explosion Point

About two-thirds up the thigh, from the knee, is the explosion point. There are two important features of the explosion point. First, the explosion point is where the bar brushes the thigh on its upward path.

Second, the explosion point determines the grip’s width so that the bar hits the explosion point where you’ve maximum capacity for hip and leg extension.

The explosion point is brought to the bar and then the hip and legs extend suddenly, driving the bar up.

Technique: The Max Extension Point

As the bar brushes the thighs, the chest is thrown upward, the shoulders shrug violently, and the athlete makes a short, flat-footed jump. This is the point of maximum extension. The arms have still not done any of the work.

The shrug and torso’s hyperextension pull the bar up and back while the bang of the thigh at the explosion tends to drive the bar out and up. The net force sends the bar up powerfully and slightly back.

Technique: The Pull Under

At the exact instant of reaching the maximum extension point, the hip violently retreats downward into a squat. Simultaneously, the arms pull the athlete down under the bar. This is the first time the arms contribute to the movement.

Technique: The Front Squat

As the elbows whip forward, the bar is caught on the chest and shoulders. Compared to the starting stance the squat is about four inches back and slightly wider to accommodate a deep squat.

Immediately on receiving the bar the athlete completes the movement by squatting to full extension.

Medicine-Ball Clean

The clean is without a doubt an advanced movement. A technically correct front squat and deadlift would seem to be obvious prerequisites to the clean, but we often introduce the medicine ball clean well before the deadlift and front squat are firmly established.

This reinforces the deadlift and squat and introduces the exciting dynamics, functionality, and metabolic potential of the clean.

The medicine ball is somewhat less intimidating than a bar, weighs less (we start with an 8-pound Dynamax and progress to the 20-pound ball), and seems to be more suggestive of the practical functionality of the clean than is the clean with the bar.

The medicine ball clean efficiently demonstrates to the developing athlete the critical sequence of the hip accelerating the object to maximum extension, the hip retreating towards the squat, and finally, the hip squatting the object to full extension.

Notice in the pictures the same fundamental features as the barbell clean – liftoff, explosion point, maximum extension point, pull under, and front squat. High-rep medicine ball cleans are a wonderful sneak peak at one of CrossFit’s more advanced training protocols – the high rep clean and jerk.

High-Rep Barbell Clean and Jerks

We have only scratched the surface of the clean. There are components like the “scoop” between the liftoff and explosion point that we are glossing over. Our hope here is threefold: first, to express the importance and potency of the clean, second, to offer fundamentals sufficient to help you effectively explore the movement, and third, to encourage additional research, discussion, exploration and coaching of the “world’s most powerful lift.”

We’ve not discussed lifting platforms, shoes, or the snatch. We leave it to you to learn as much about the clean and Olympic lifting as you can.

Strength and the Clean

It has long been our observation that an athlete’s max clean will in large part be dependent on their max deadlift and front squat.

For a load to come up from the ground confidently and then accelerated dramatically it better be an easy deadlift. Any load you attempt to clean should be an easy load for a deadlift.

To confidently dive under a load and catch it in a front squat it will need to be an easy front squat. Any load you attempt to clean should be an easy load for a front squat.

As a rule of thumb we encourage our athletes to push their combined max front squat and deadlift to four times their max clean. This suggests that if you want a 500-pound clean you’ll want to develop a 1,000- pound deadlift and a 1,000-pound front squat. In a less otherworldly example don’t expect to clean 200 pounds when your max front squat is 200 pounds and your max deadlift is 300.

Improving your front squat and deadlift is a surefire way to improve your clean.

Our favorite resources for exploring and developing the clean

- World Class Coaching, LLC’s Coach Steve Miller has produced what we consider the most advanced and authoritative instructional material on the clean available anywhere in the videotape “The World’s Most Powerful Lift”.

- Bob White is a protégé of Coach Miller’s and is Texas State age group weightlifting champion. Bob is an engineer and his careful analysis of the kinematics of the clean at the end of both World Class Coaching tapes is truly revolutionary in its startling conclusion.

- IronMind produces MILO, the best strength journal anywhere, fantastic equipment, videotapes, and posters related to weightlifting and serious strength training.

- David Webster’s “Development of the Clean and Jerk.” David Webster is a legendary weightlifting coach and his “Development of the Clean and Jerk” is a 46-page gem. Available only from IronMind this little book is in limited supply – get it now.

- USA Weightlifting is the national governing body of weightlifting in the U.S

- Dan John’s Lifting and Throwing Page is a veritable treasure trove of serious weightlifting information.

- Arthur Drechsler’s “The Encyclopedia of Weightlifting” available from IronMind. This 500-page behemoth is dedicated to only two lifts – the clean and jerk and the snatch.

The Clean and the Clean and Jerk

We mentioned that the clean is a gateway exercise to the clean and jerk. The clean and jerk is not only one of the two Olympic lifts; it is also an extraordinary movement of unparalleled capacity to advance your fitness.

The clean will be the weak link in the clean and jerk. If you can get under the weight, you’ll likely be able to squat the weight and then drive it overhead.

We want a big clean so that we can get a big clean and jerk so that you can get a big high rep clean and jerk.

Why a Big High-Rep Clean and Jerk?

Of the ten general physical skills (cardiorespiratory endurance, stamina, strength, flexibility, power, speed, coordination, agility, balance, and accuracy) the high-rep clean and jerk is the only single exercise protocol we know of that can substantially increase all ten!

An athlete able to perform a 225-pound clean and jerk for fifteen reps at a bodyweight of 200 pounds is surely “CrossFit.”

That the world’s greatest developer of power and speed isn’t traditionally practiced at higher reps is a shortcoming that cannot be logically explained.

The Fifteen-Rep Clean and Jerk

For the fifteen-rep clean and jerk challenge, we allow only touch and go at the ground but allow any break wanted at rack, overhead, and hang positions. (Resting here doesn’t buy much relief.)

Typically we perform three sets at the same weight. One at 15 reps, another at 12 reps, and a third at 9 reps. The 15-12-9 progression completely covers the time domain of the all-important middle metabolic pathway, the glycolytic.

At fifteen reps the clean and jerk combines the cardiorespiratory demands of an 800-meter run in a nauseating brew of function, strength, coordination, and power.

Conclusion

The “king of all exercises” contains two classic exercises, the deadlift and the squat, and is itself a component of another classic, the clean and jerk.

This classic of strength and power demands as much speed, flexibility, coordination, balance, accuracy, as any sport and at higher reps is a better cardiovascular stimulus than bicycling.

The clean, both an end and a means, marks the point where weight training becomes sport. As hard to master as the violin, every minute of practicing and training for this move is a minute well spent.

- Download Original PDF

- Download Español (Spanish) PDF

- Download Português (Portuguese) PDF

- Download Italiano (Italian) PDF

- Download Français (French) PDF

Greg Glassman founded CrossFit, a fitness revolution. Under Glassman’s leadership there were around 4 million CrossFitters, 300,000 CrossFit coaches and 15,000 physical locations, known as affiliates, where his prescribed methodology: constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity, were practiced daily. CrossFit became known as the solution to the world’s greatest problem, chronic illness.

In 2002, he became the first person in exercise physiology to apply a scientific definition to the word fitness. As the son of an aerospace engineer, Glassman learned the principles of science at a young age. Through observations, experimentation, testing, and retesting, Glassman created a program that brought unprecedented results to his clients. He shared his methodology with the world through The CrossFit Journal and in-person seminars. Harvard Business School proclaimed that CrossFit was the world’s fastest growing business.

The business, which challenged conventional business models and financially upset the health and wellness industry, brought plenty of negative attention to Glassman and CrossFit. The company’s low carbohydrate nutrition prescription threatened the sugar industry and led to a series of lawsuits after a peer-reviewed journal falsified data claiming Glassman’s methodology caused injuries. A federal judge called it the biggest case of scientific misconduct and fraud she’d seen in all her years on the bench. After this experience Glassman developed a deep interest in the corruption of modern science for private interests. He launched CrossFit Health which mobilized 20,000 doctors who knew from their experiences with CrossFit that Glassman’s methodology prevented and cured chronic diseases. Glassman networked the doctors, exposed them to researchers in a variety of fields and encouraged them to work together and further support efforts to expose the problems in medicine and work together on preventative measures.

In 2020, Greg sold CrossFit and focused his attention on the broader issues in modern science. He’d learned from his experience in fitness that areas of study without definitions, without ways of measuring and replicating results are ripe for corruption and manipulation.

The Broken Science Initiative, aims to expose and equip anyone interested with the tools to protect themself from the ills of modern medicine and broken science at-large.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

How a Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Naturally Activates the Same Pathways

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life