Learning the progression of lifts that moves from the shoulder press to the push press to the push jerk has long been a staple of the CrossFit regimen. This progression offers the opportunity to acquire some essential motor recruitment patterns found in sport and life (functionality) while greatly improving strength in the “power zone” and upper body. In terms of power zone and functional recruitment patterns, the push press and push jerk have no peer among the other presses like the “king” of upper body lifts, the bench press.

As the athlete moves from shoulder press to push press to push jerk, the importance of core-to-extremity muscle recruitment is learned and reinforced. This concept alone would justify the practice and training of these lifts. Core-to-extremity muscular recruitment is foundational to the effective and efficient performance of athletic movement. The most common errors in punching, jumping, throwing and a multitude of other athletic movements typically express themselves as a violation of this concept.

Because good athletic movement begins at the core and radiates to the extremities, core strength is absolutely essential to athletic success. The region of the body from which these movements emanate, the core, is often referred to as the “power zone.” The muscle groups comprising the “power zone” include the hip flexors, hip extensors (glutes and hams), spinal erectors and quadriceps. These lifts are enormous aids to developing the power zone.

Additionally, the advanced elements of the progression, the push press and jerk, train for and develop power and speed. Power and speed are “king” in sport performance. Coupling force with velocity is the very essence of power and speed. Some of our favorite and most developmental lifts lack this quality. The push press and jerk are performed explosively—that is the hallmark of speed and power training.

Finally, mastering this progression gives an ideal opportunity to detect and eliminate a postural/mechanical fault that plagues more athletes than not—the pelvis “chasing” the leg during hip flexion. This fault needs to be searched out and destroyed. The push press performed under great stress is the perfect tool to conjure up this performance wrecker so it can be eliminated.

Mechanics

The Shoulder Press

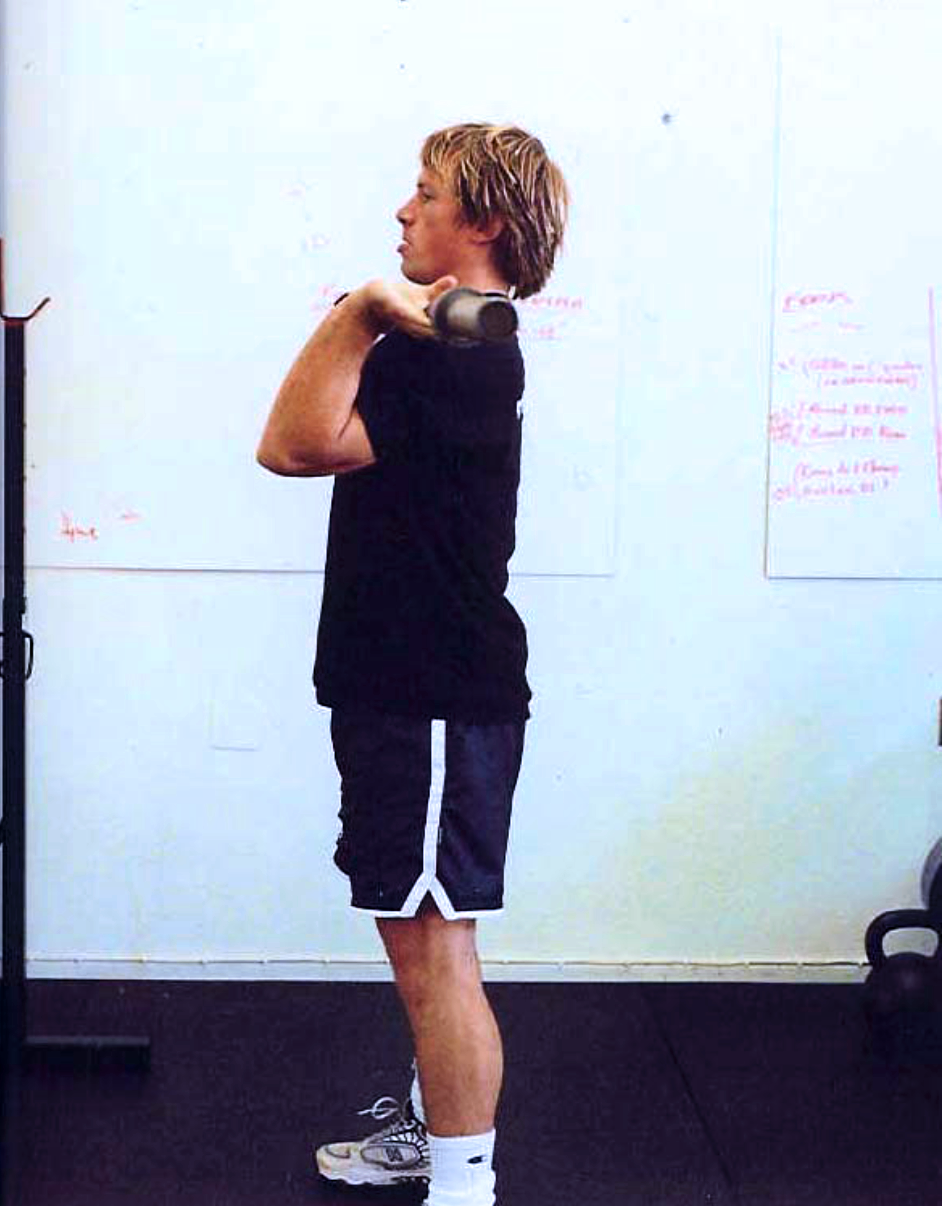

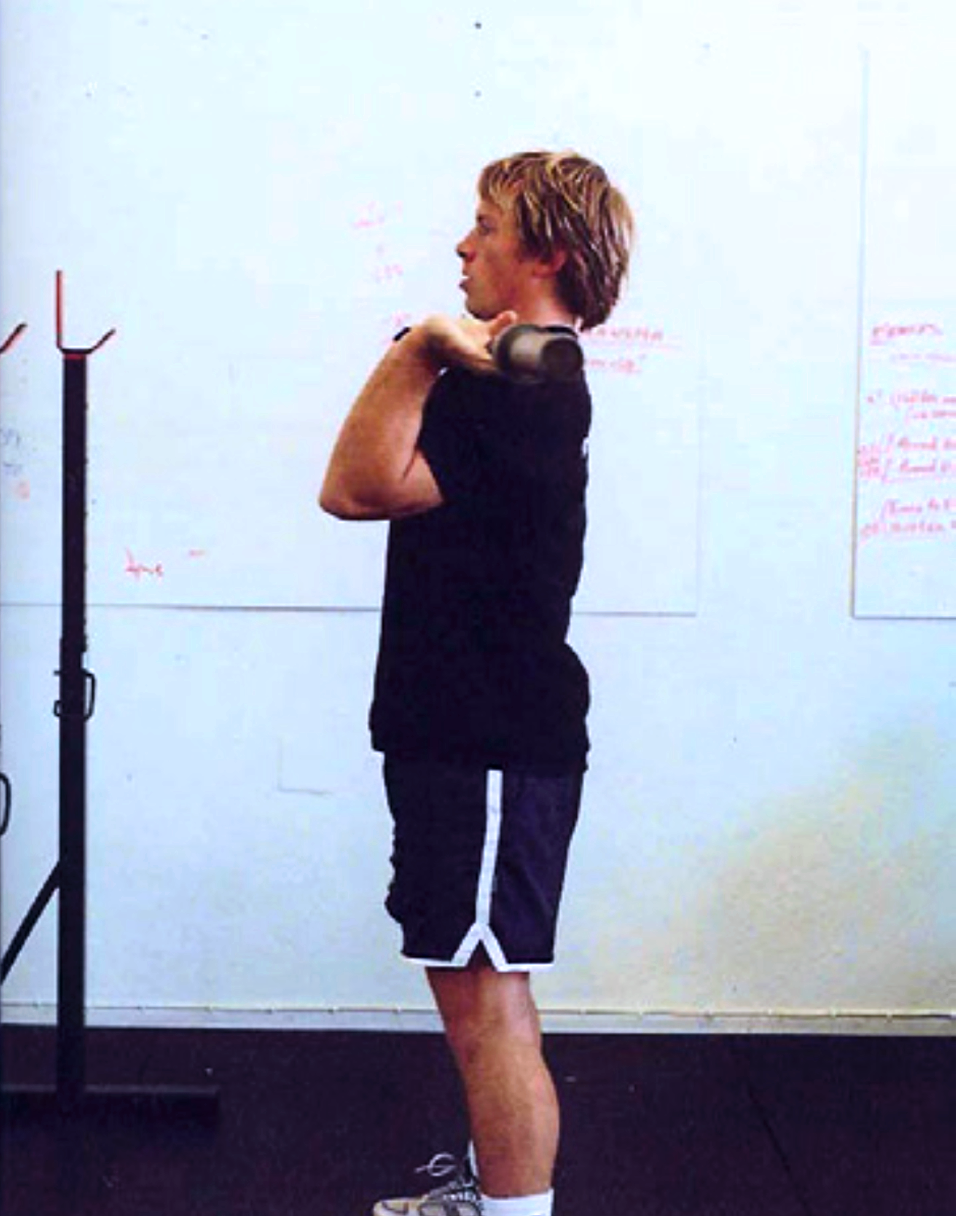

- Set-up: Take bar from supports or clean to racked position. The bar sits on the shoulders with the grip slightly wider than shoulder width. The elbows are below and in front of bar. Stance is approximately shoulder width. Head is tilted slightly back, allowing bar to pass.

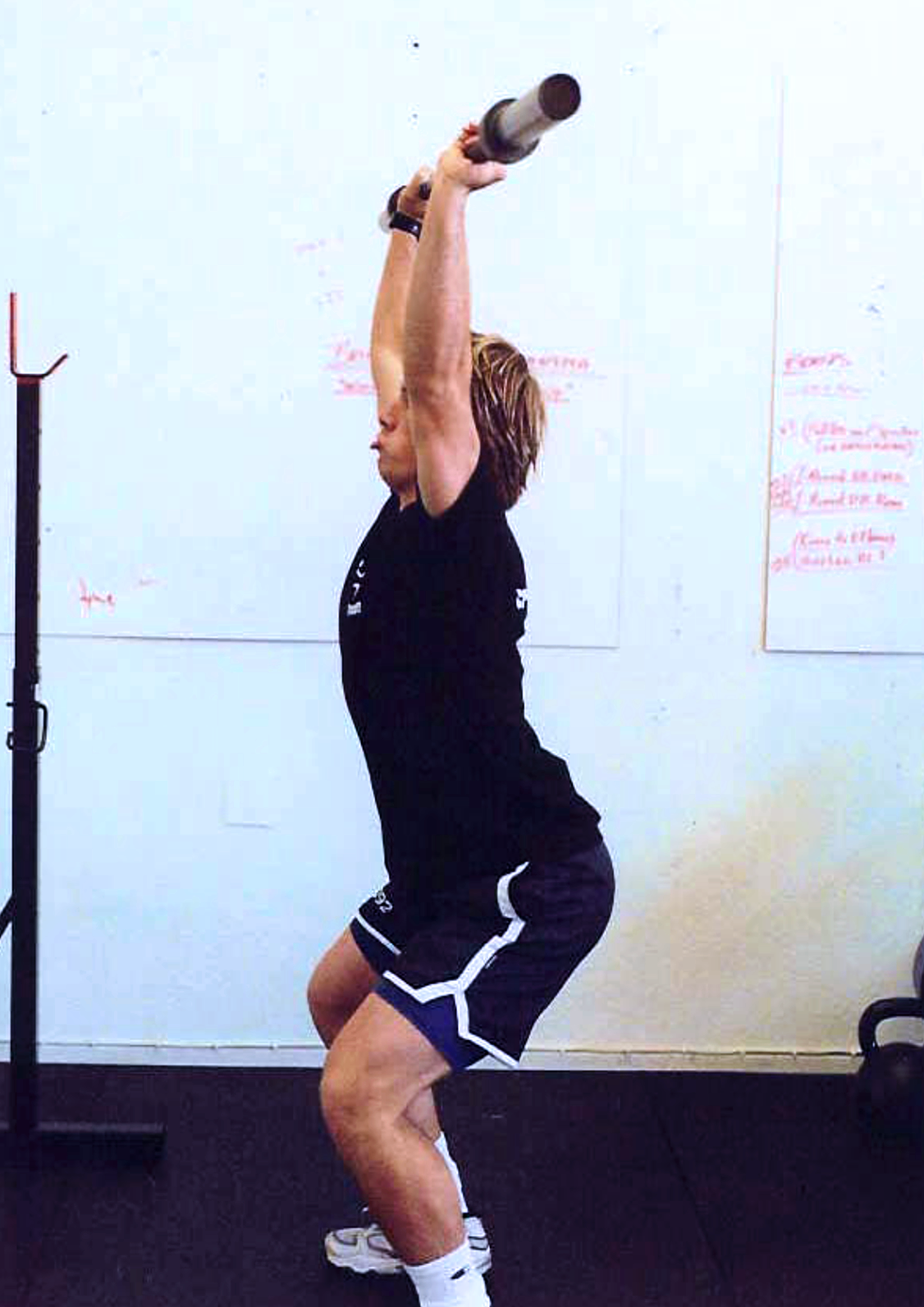

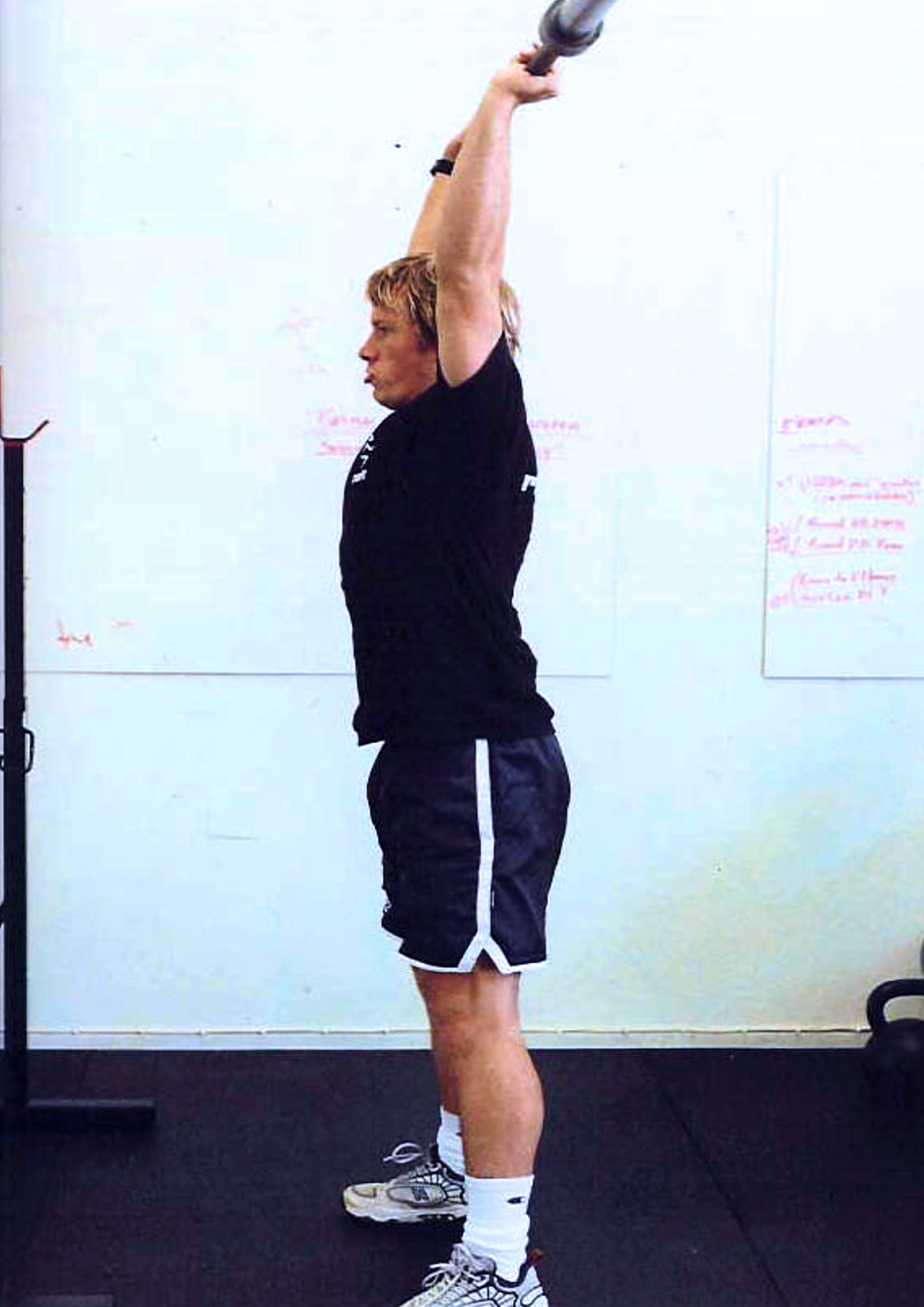

- Press: Press the bar to a position directly overhead.

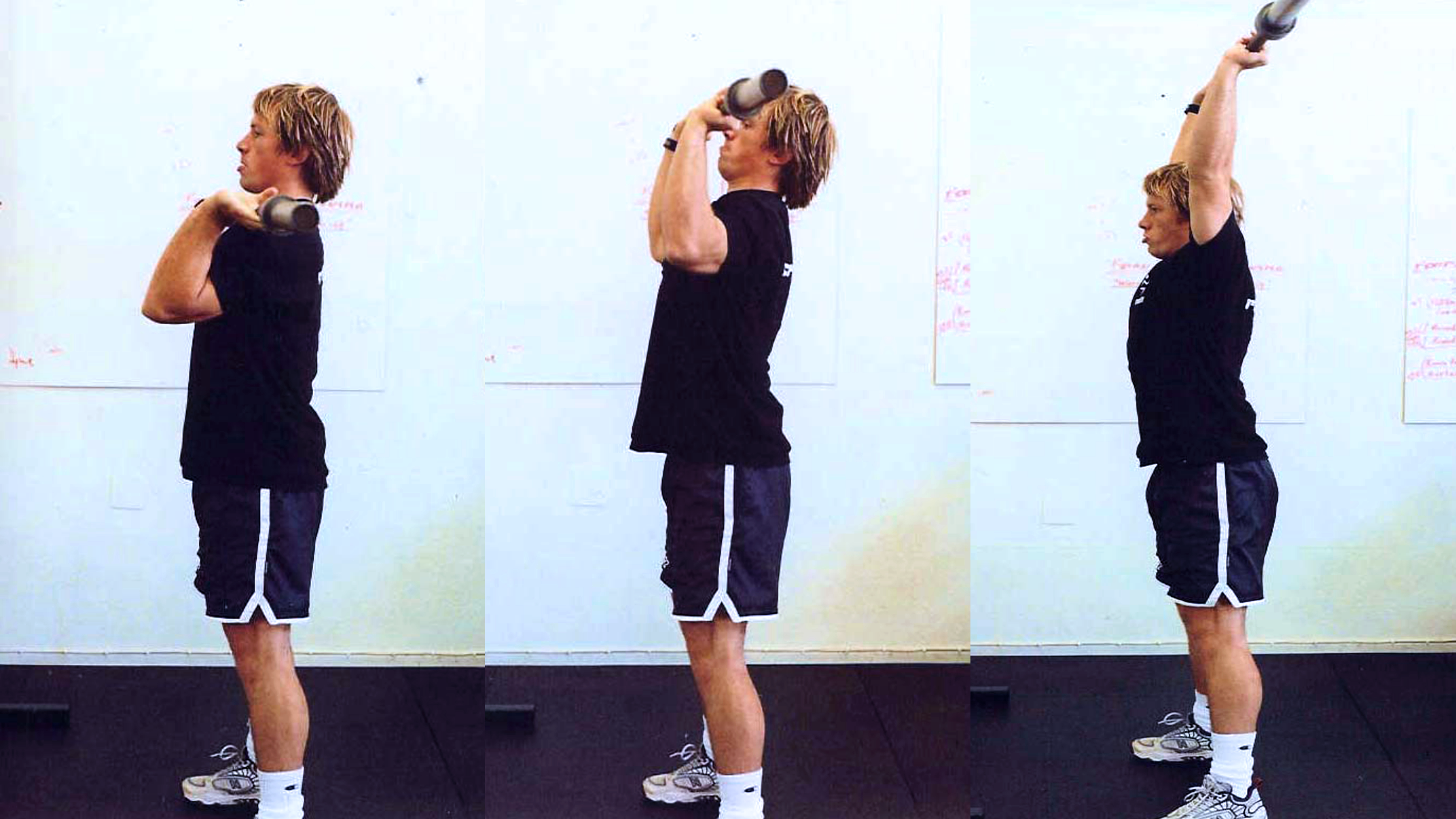

The Push Press

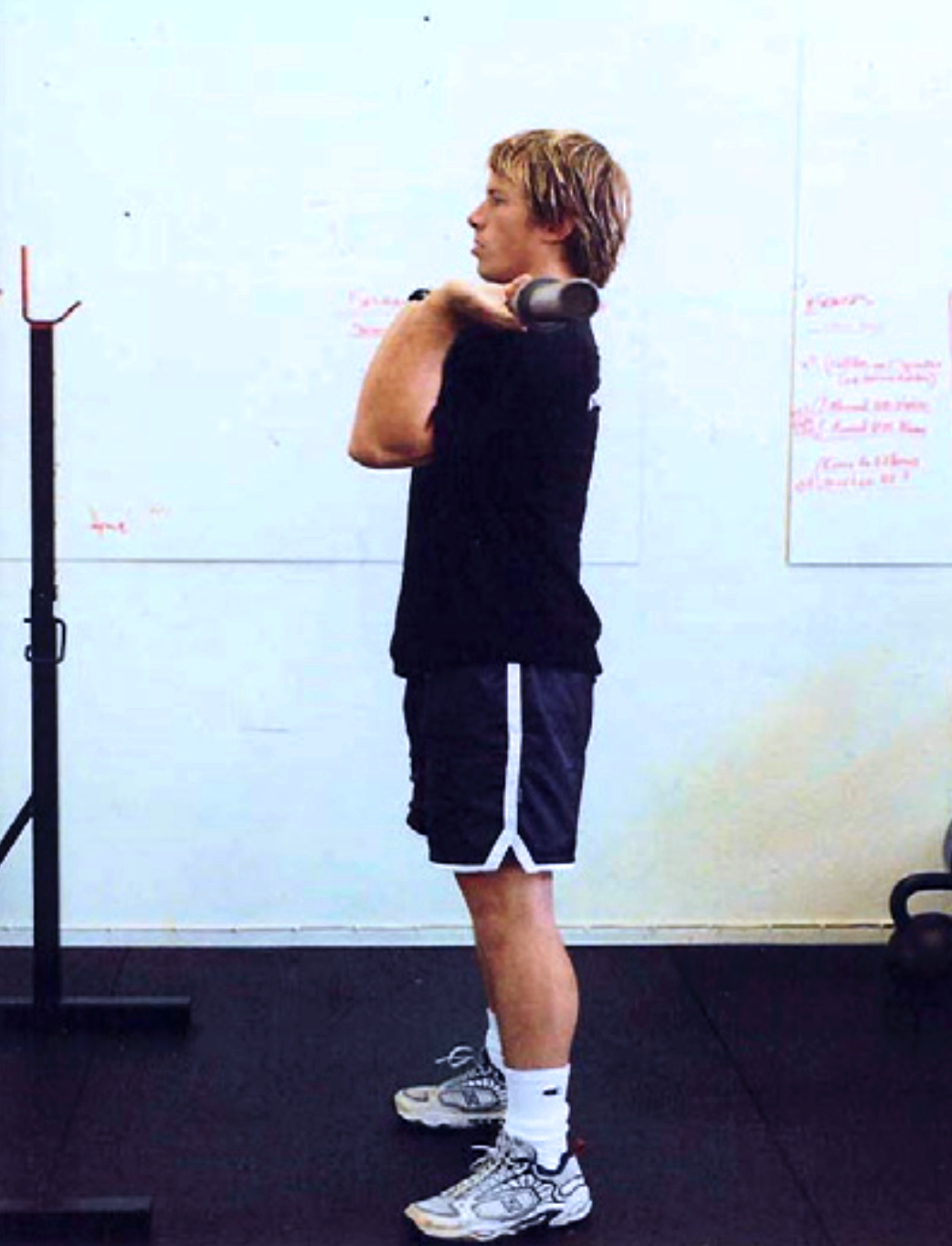

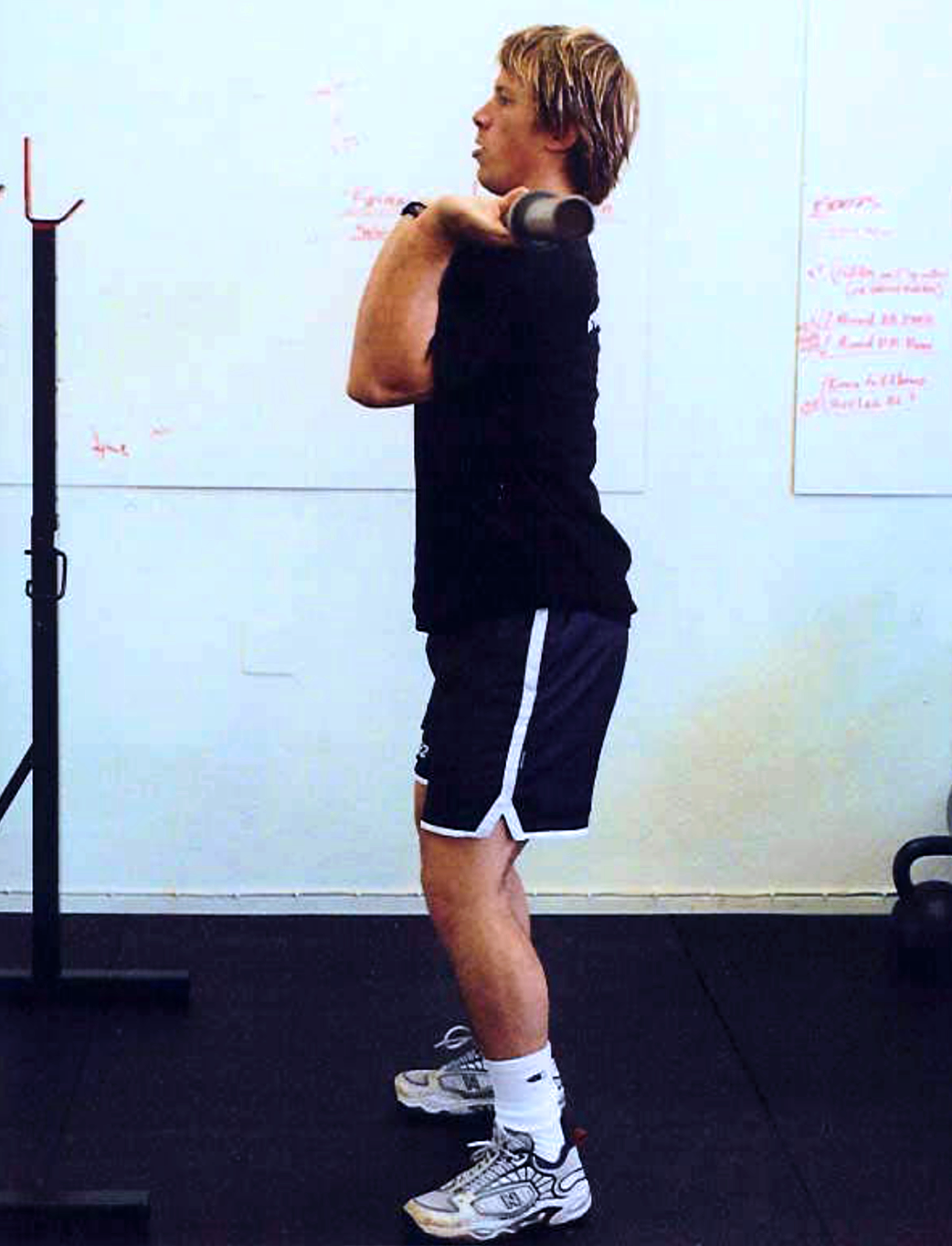

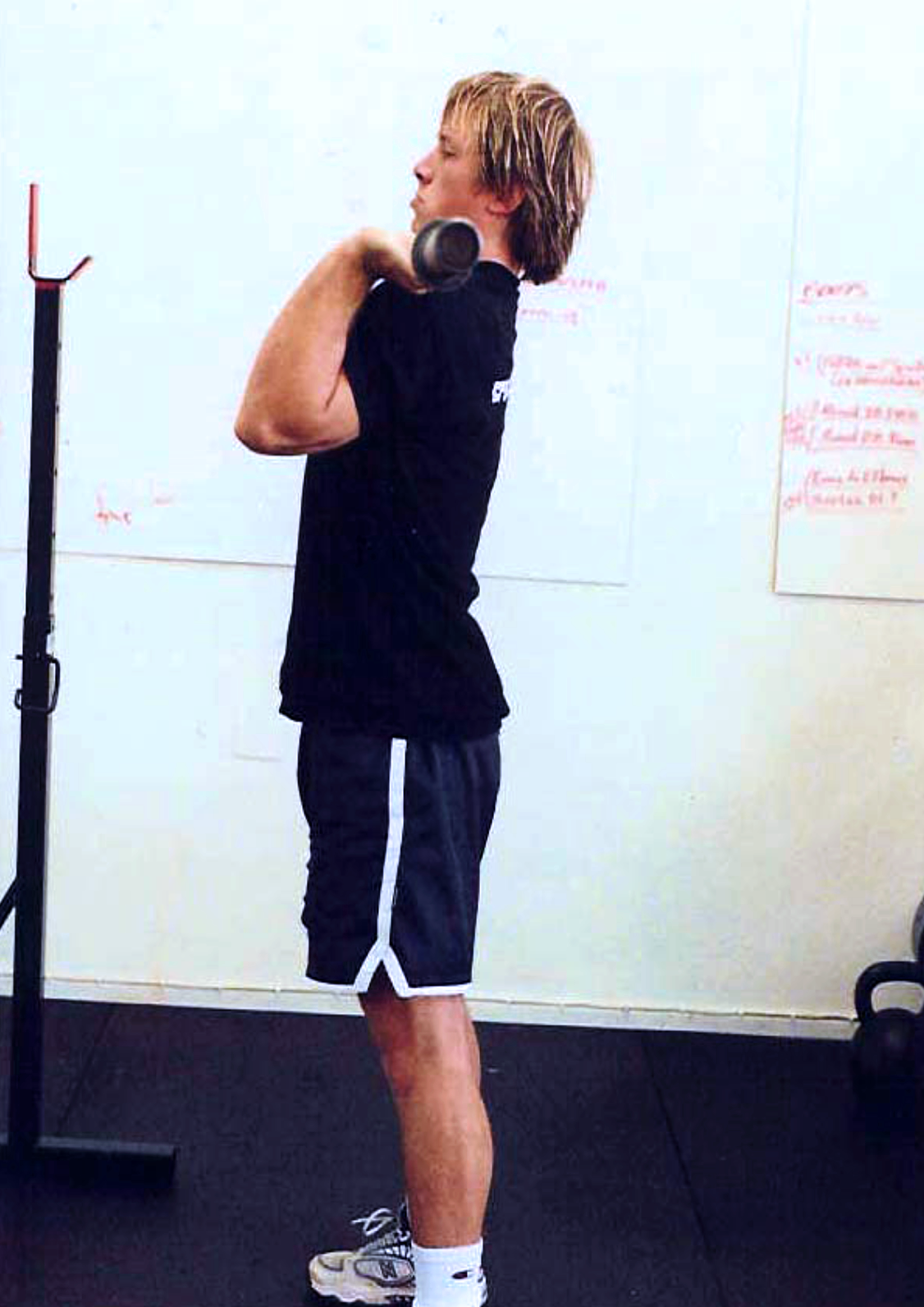

- Set-up: The set-up is the same as the shoulder press.

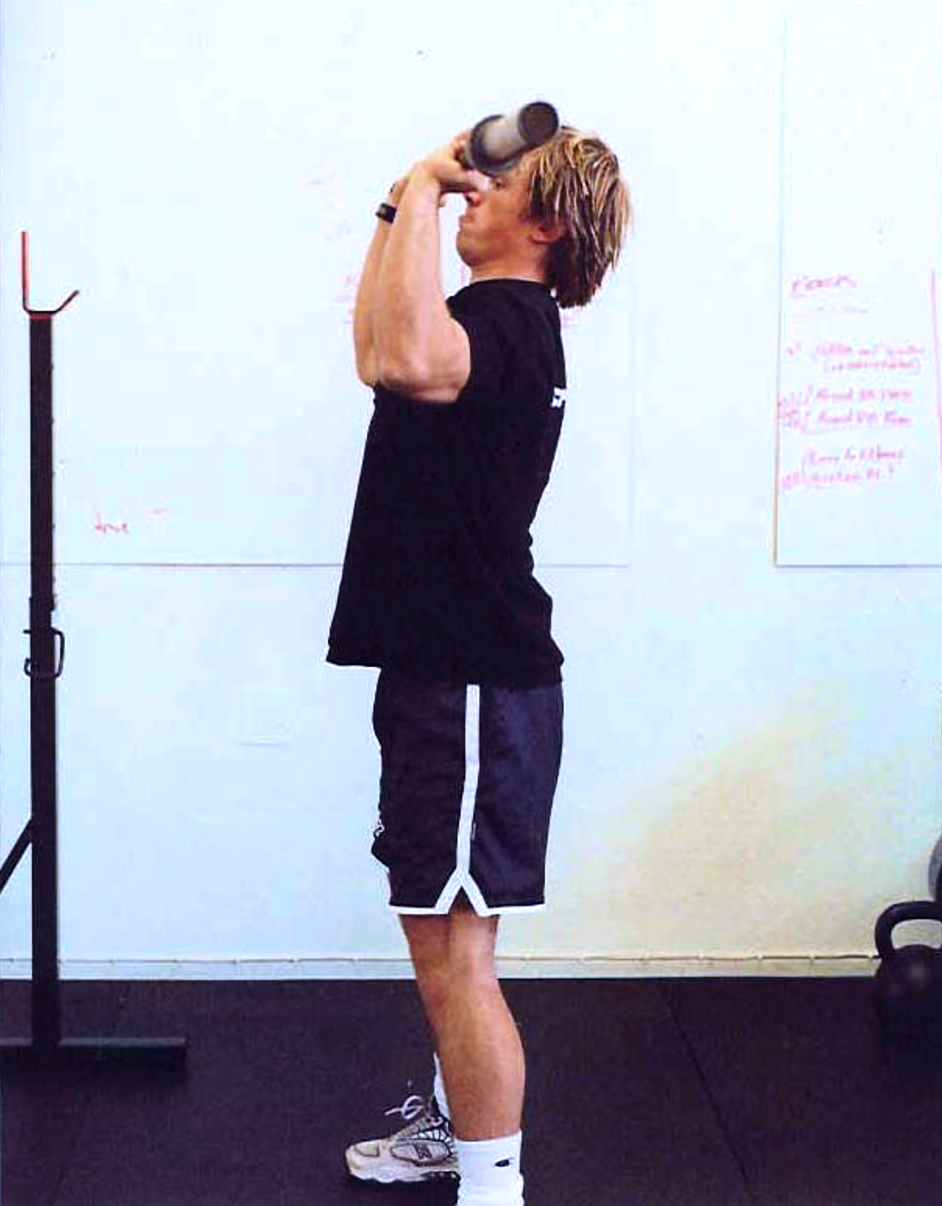

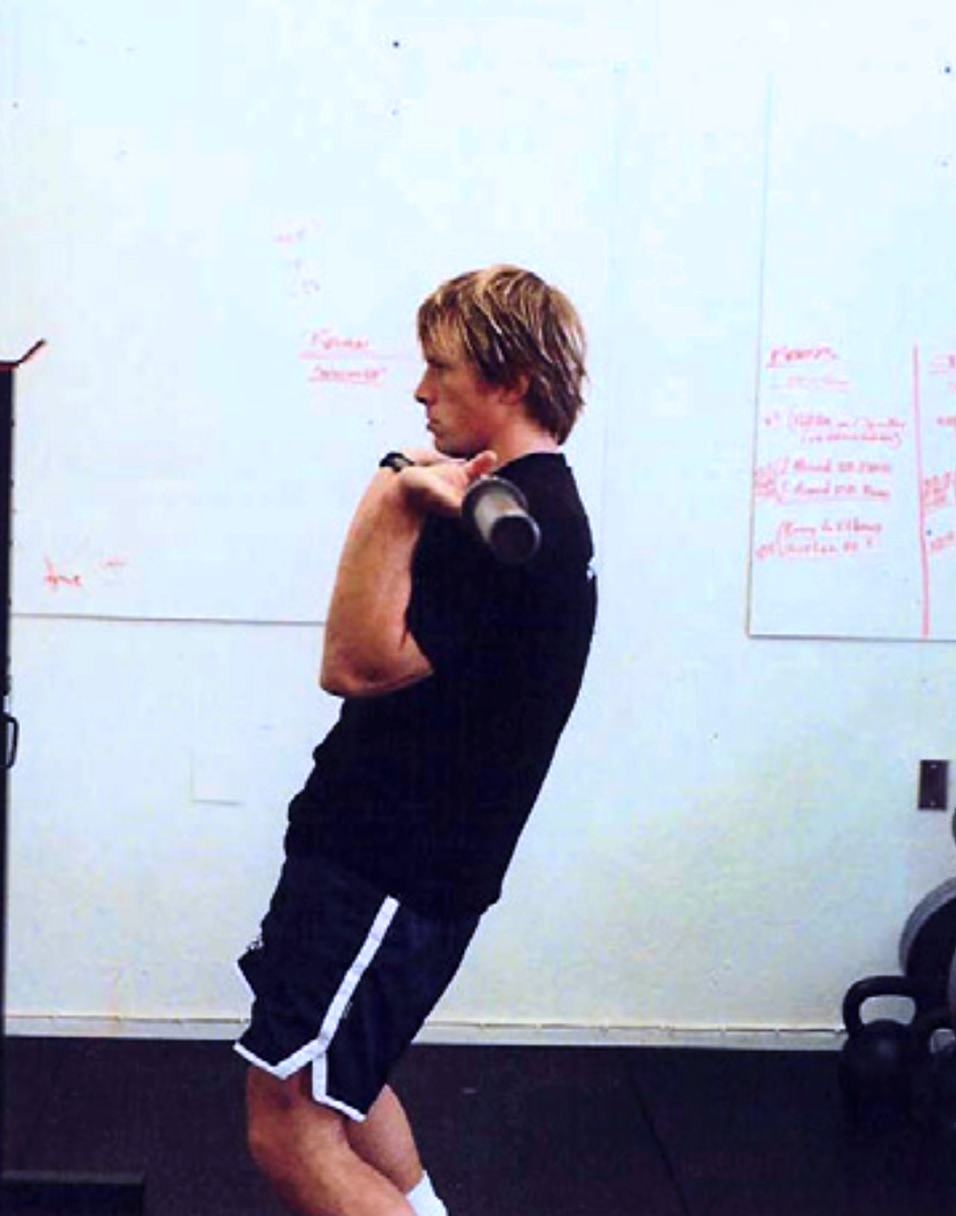

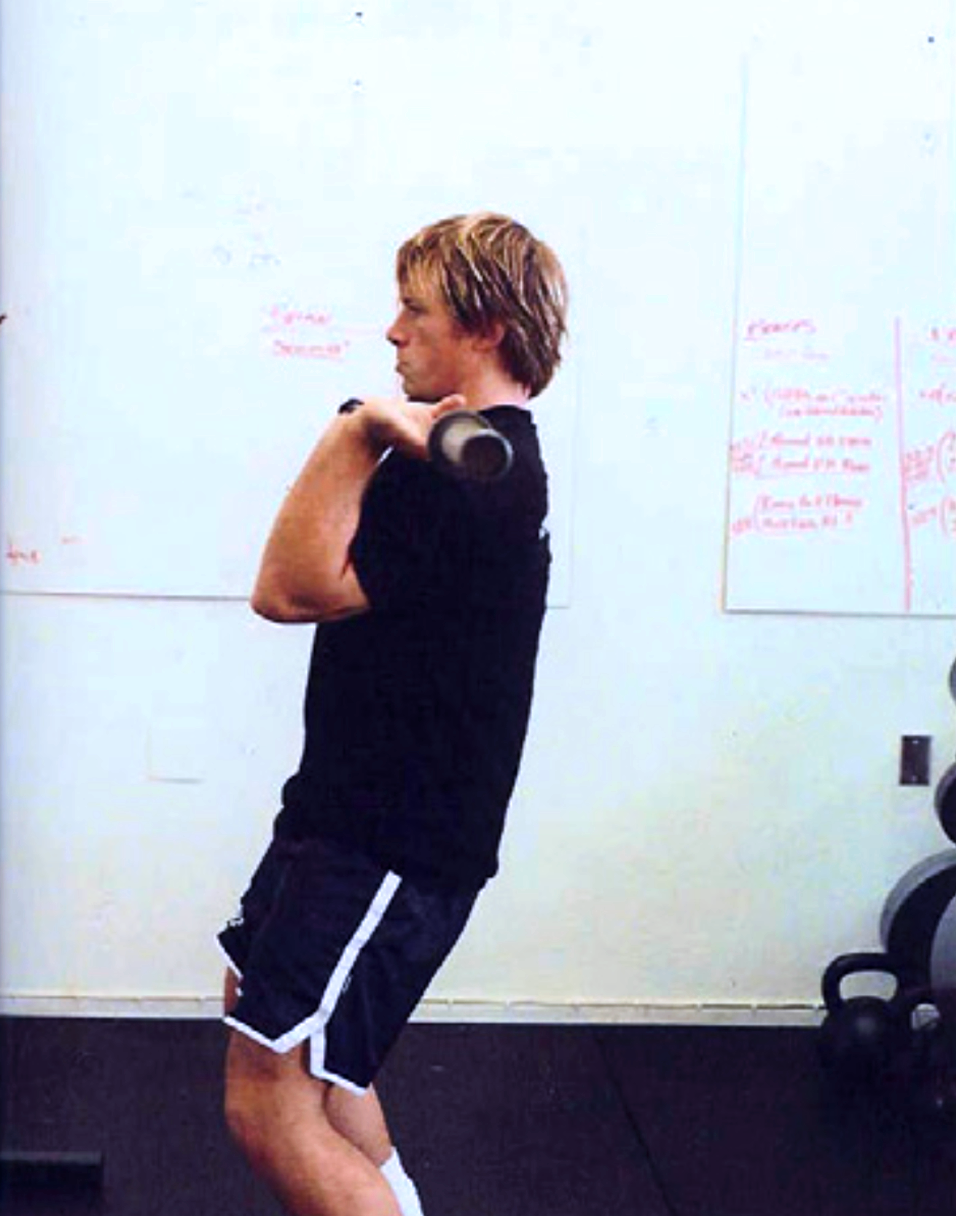

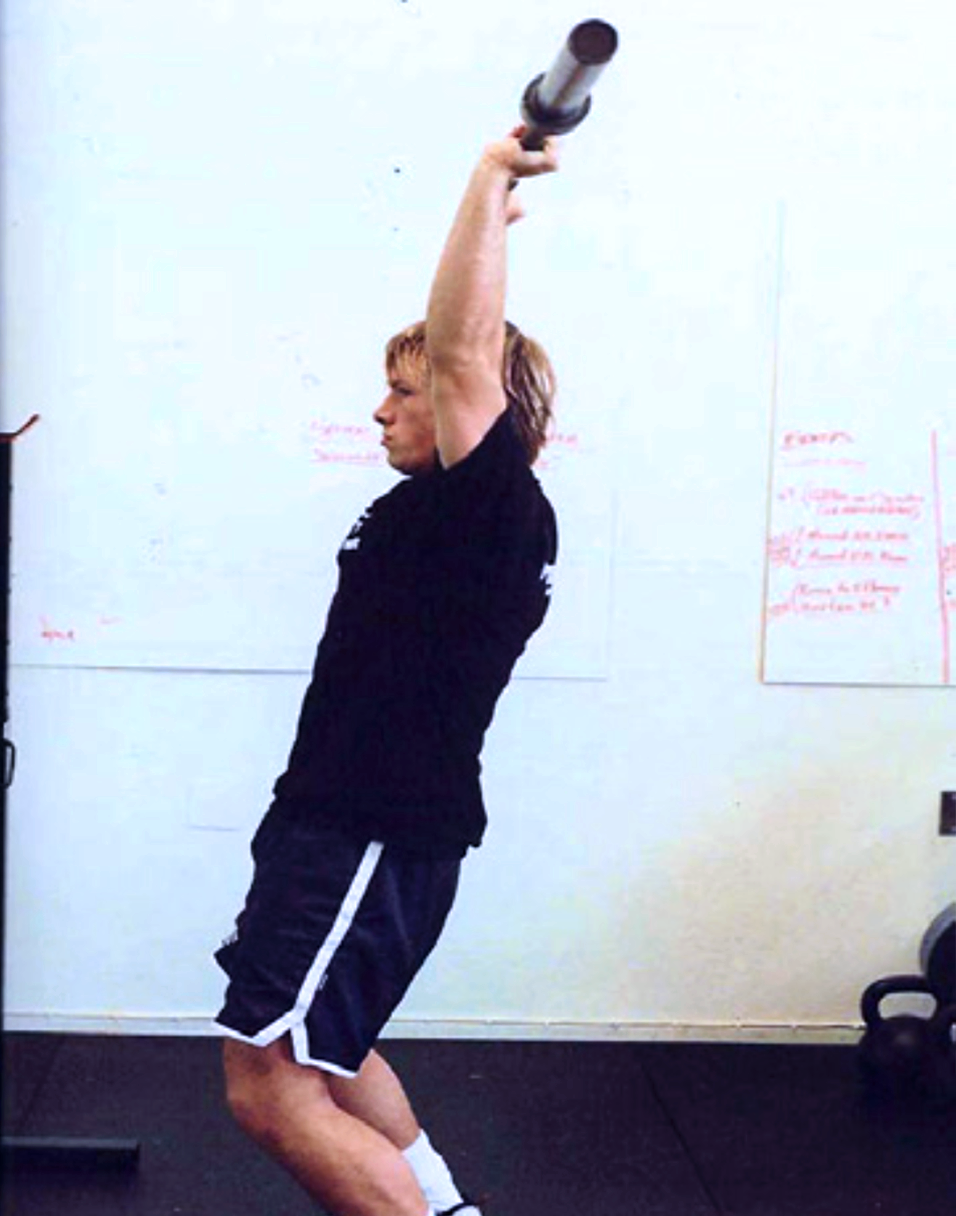

- Dip: Initiate the dip by bending the hips and knees while keeping the torso upright. The dip will be between 1/5 and 1/4 of a squat in depth.

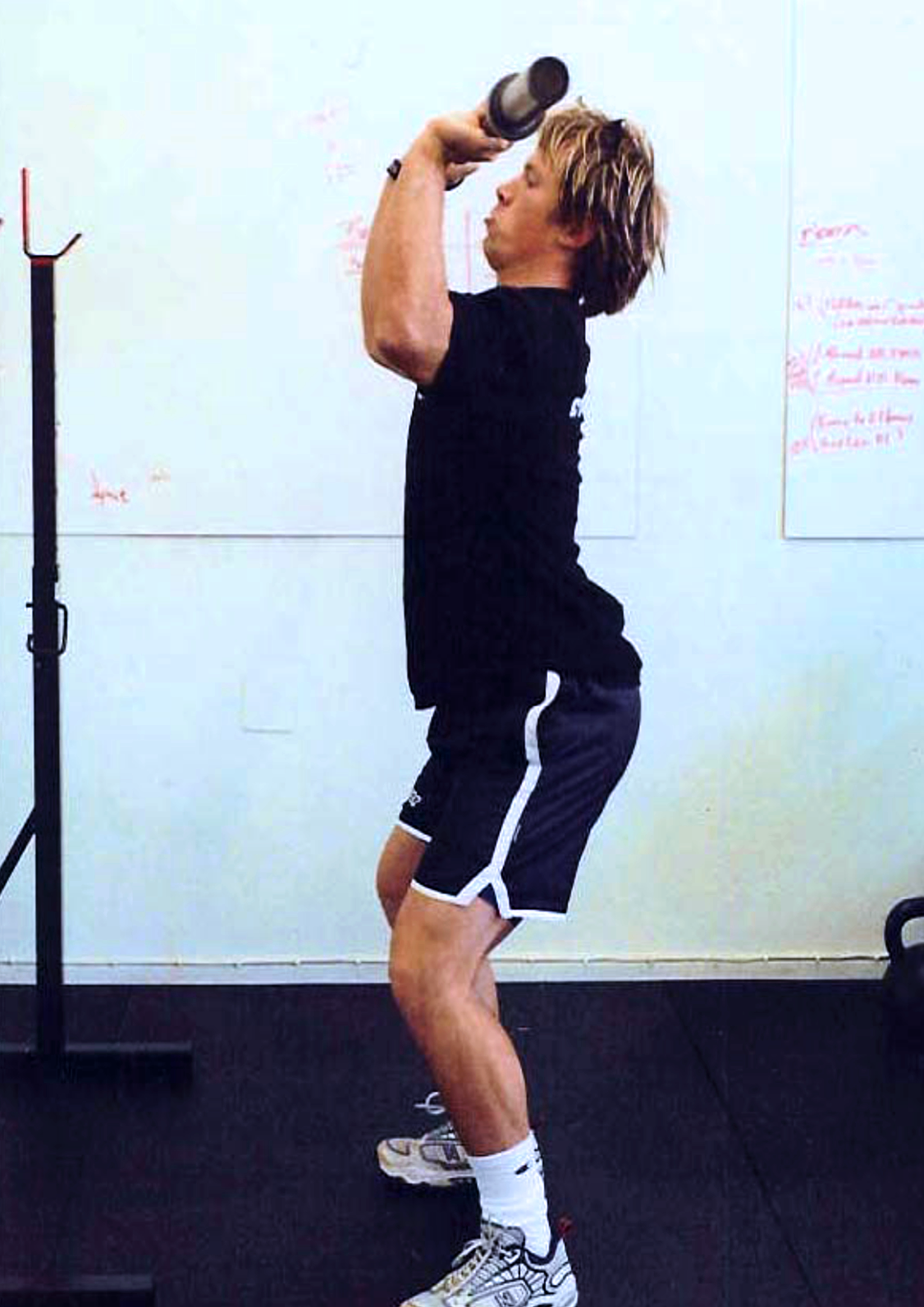

- Drive: With no pause at the bottom of the dip, the hips and legs are forcefully extended.

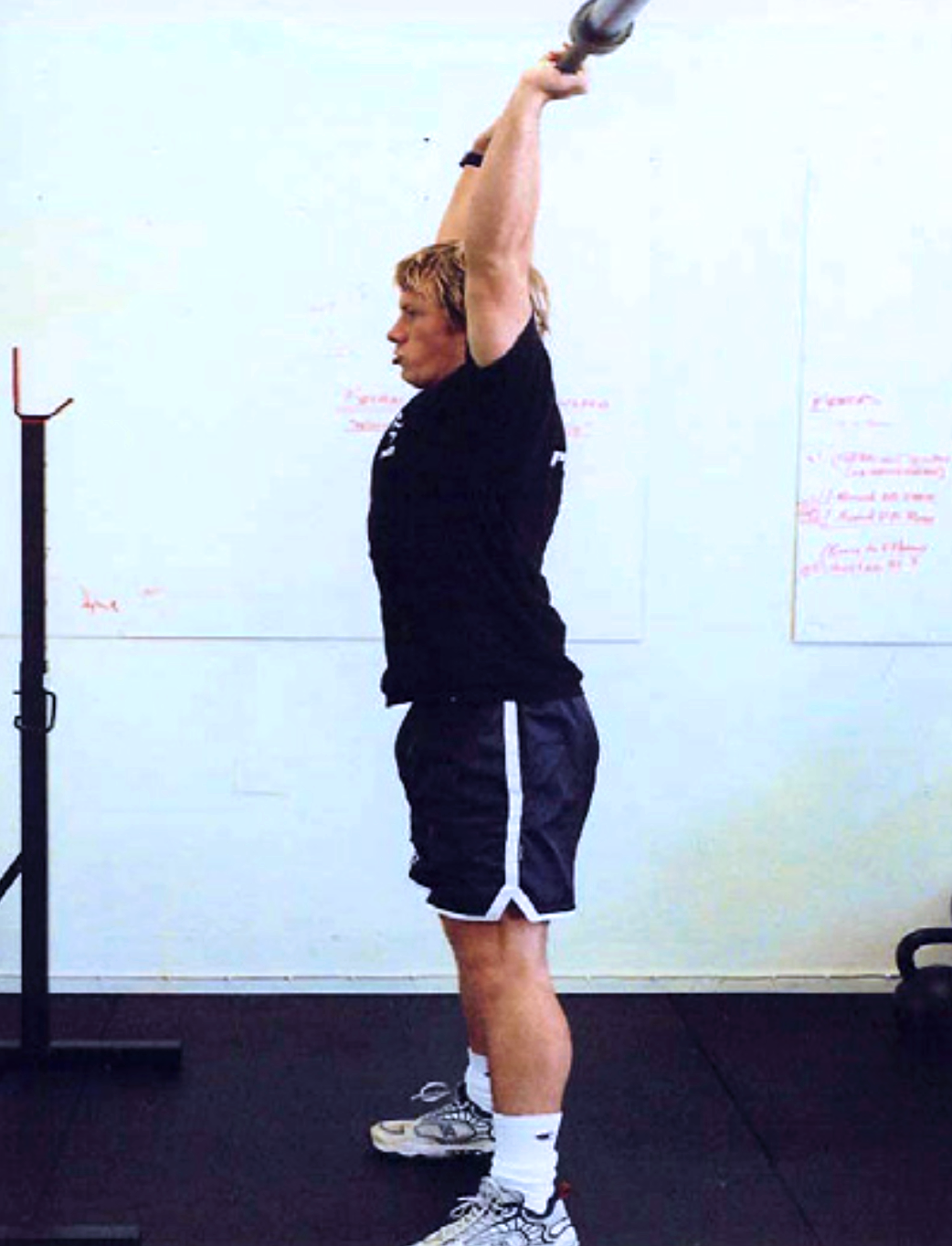

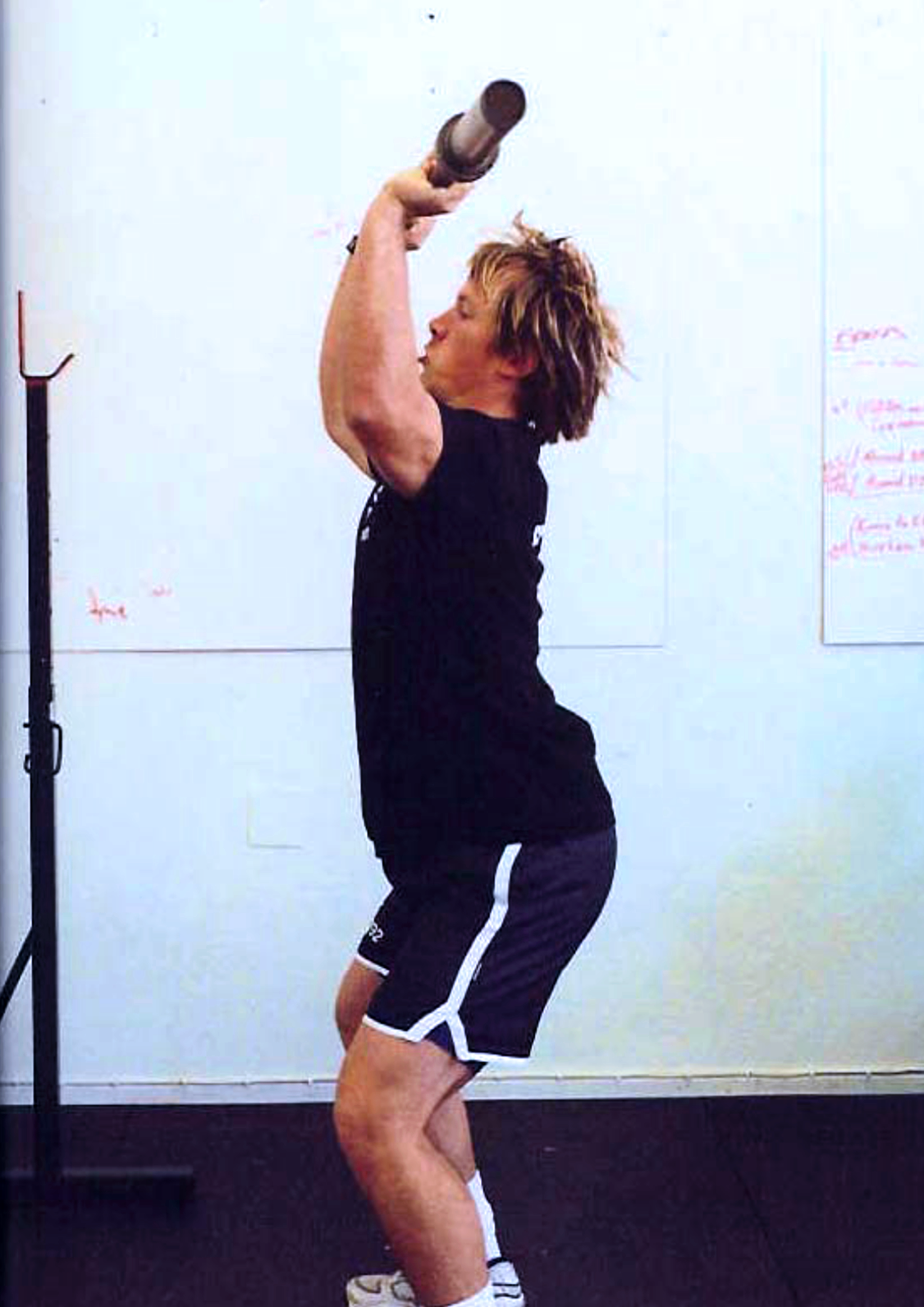

- Press: As the hips and legs complete extension, the shoulders and arms forcefully press the bar overhead until the arms are fully extended.

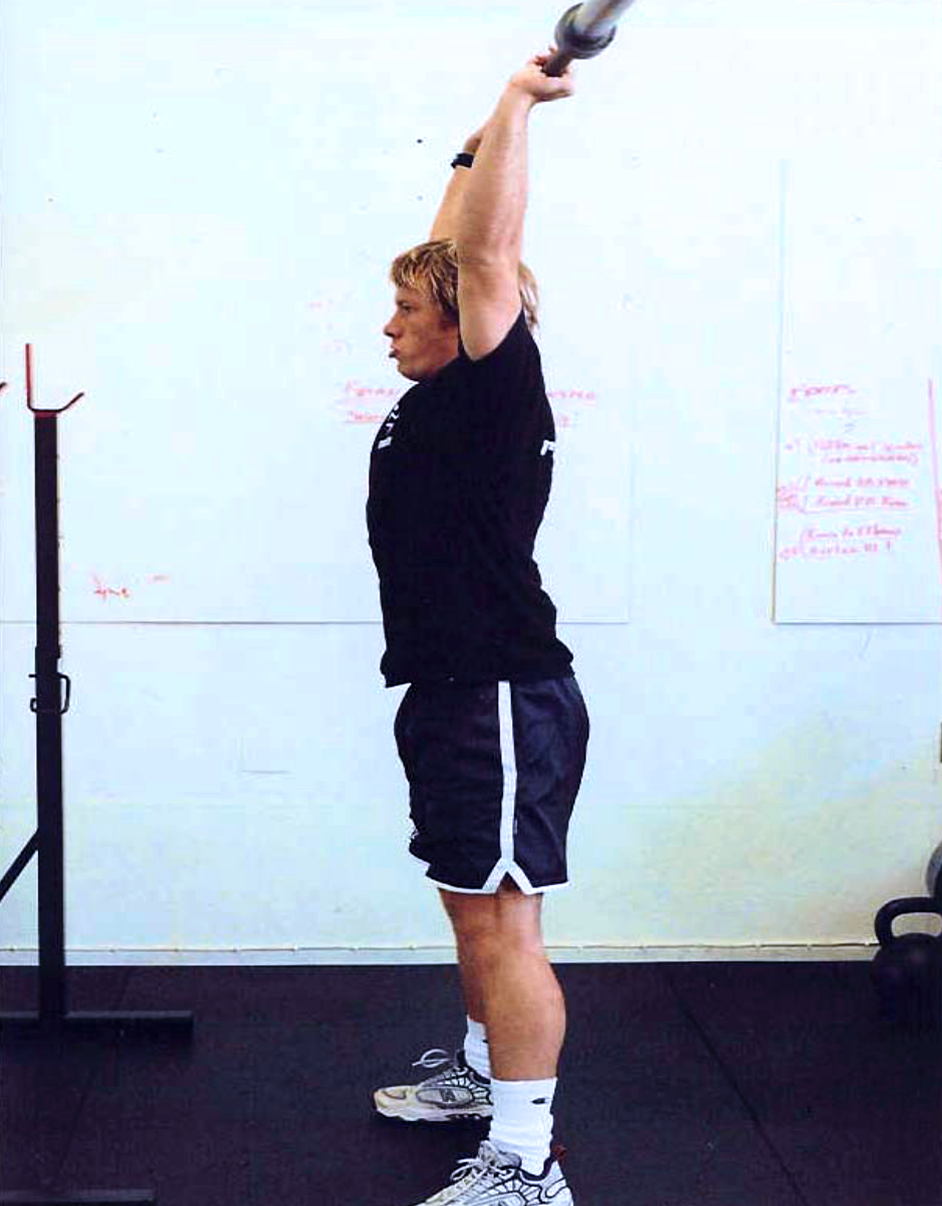

The Push Jerk

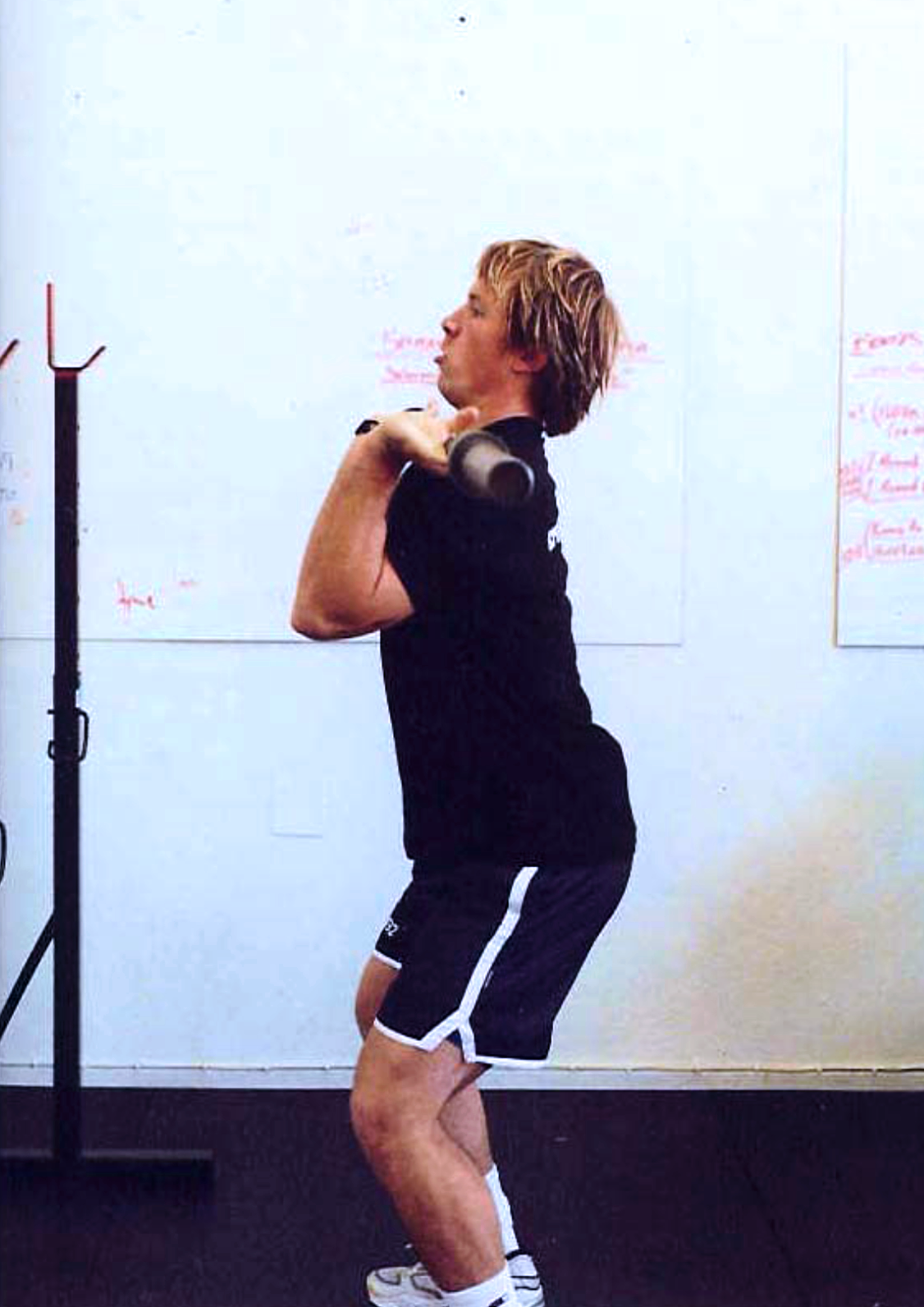

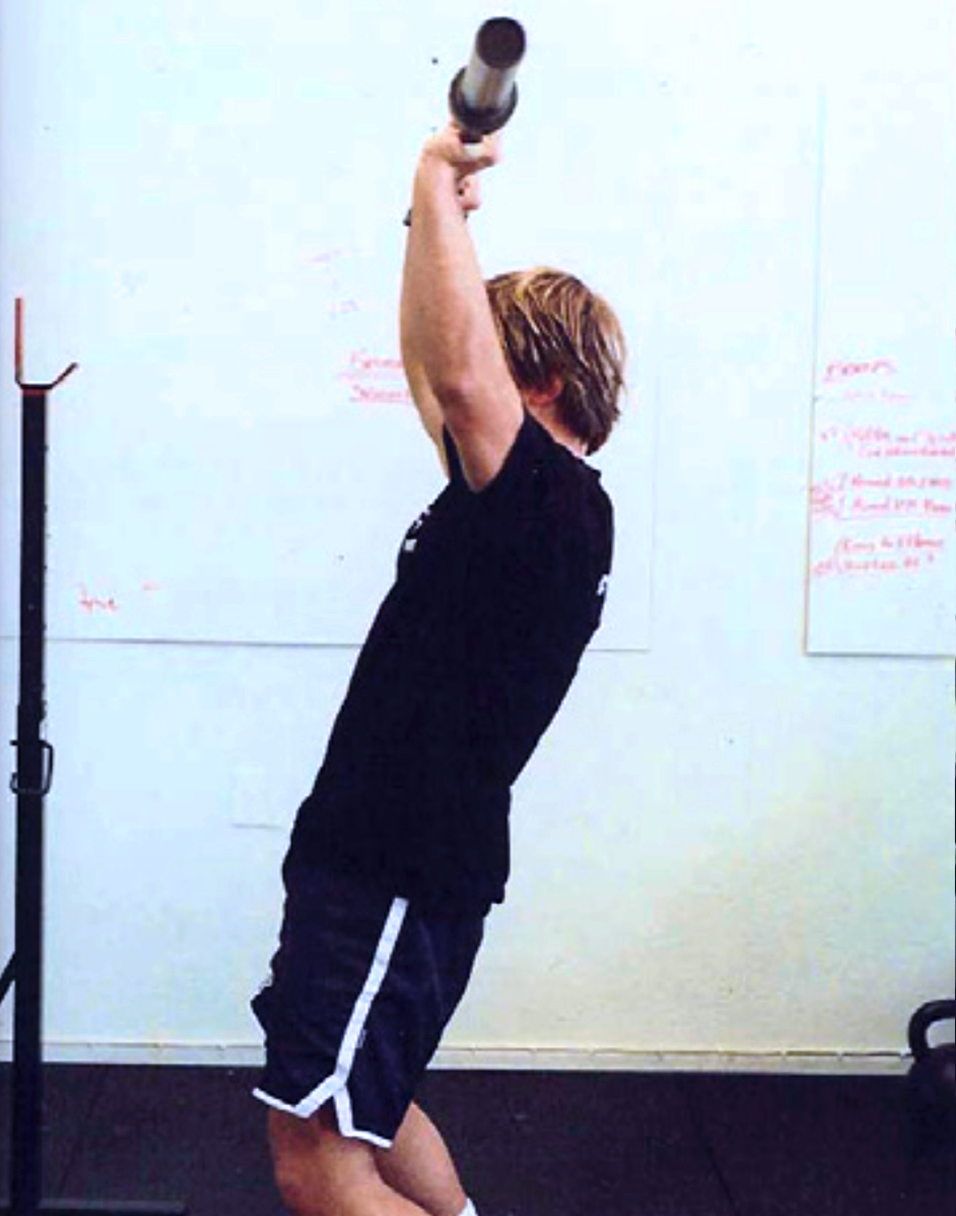

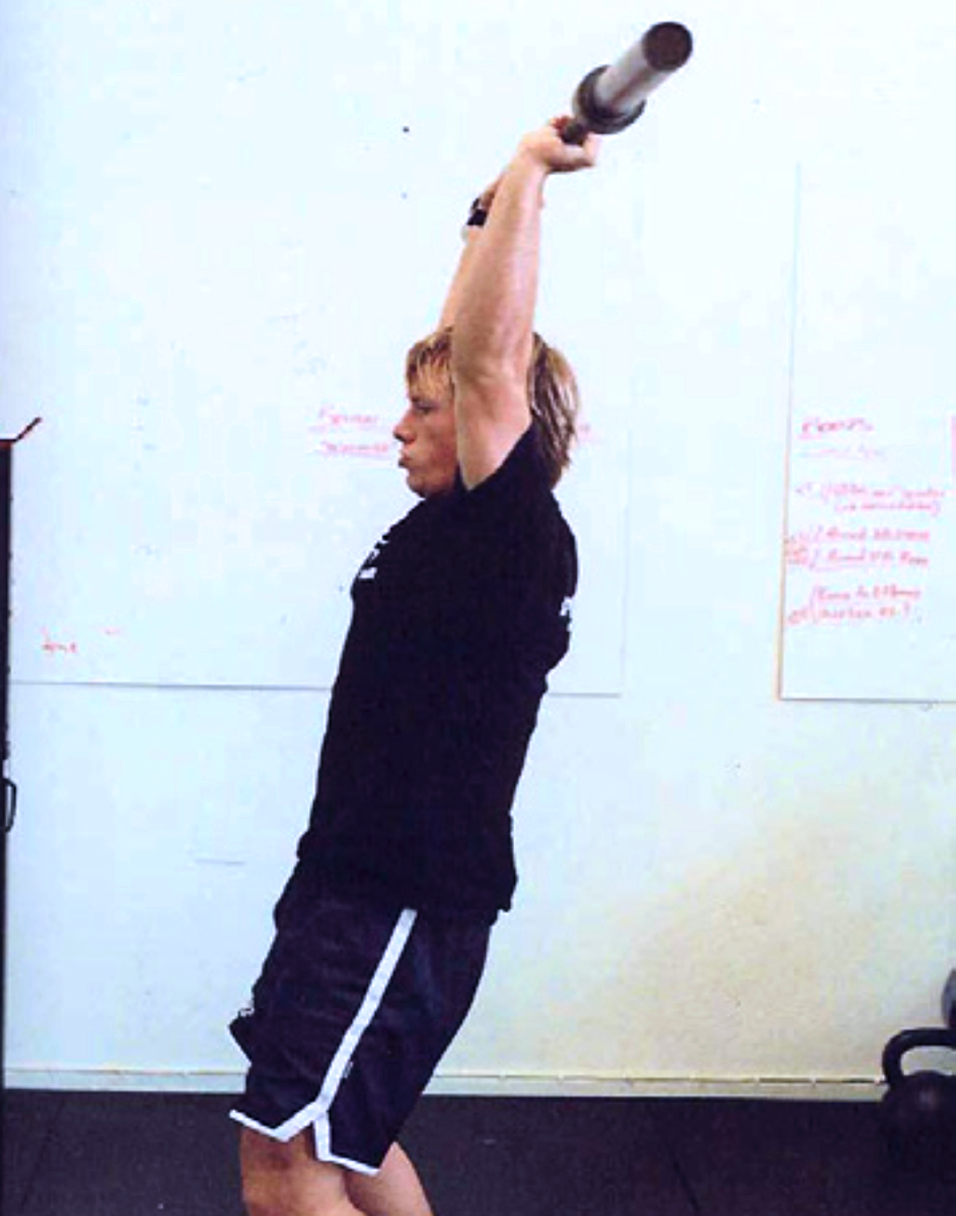

- Set-up: The set-up is the same as for the shoulder press and push press.

- Dip: The dip is identical to the push press.

- Drive: The drive is identical to the push press.

- Press and Dip: This time, instead of just pressing, you press and dip a second time simultaneously, catching the bar in a partial squat with the arms fully extended overhead.

- Finish: Stand or squat to fully erect with bar directly overhead, identical to terminal position in push press and shoulder press.

The Role of the Abs in the Overhead Lifts

Athletically, the abdominals’ primary role is midline stabilization, not trunk flexion. They are critical to swimming, running, cycling and jumping, but never is their stabilizing role more critical than when attempting to drive loads overhead, and, of course, the heavier the load, the more critical the abs’ role becomes. We train our athletes to think of every exercise as an ab exercise, but in the overhead lifts it’s absolutely essential to do so. It is easy to see when an athlete is not sufficiently engaging the abs in an overhead press—the body arches so as to push the hips, pelvis and stomach ahead of the bar. Constant vigilance is required of every lifter to prevent and correct this postural deformation.

Summary

From shoulder press to push jerk the movements become increasingly more athletic, functional and suited to heavier loads. The progression also increasingly relies on the power zone. In the shoulder press, the power zone is used for stabilization only. In the push press, the power zone provides not only stability, but also the primary impetus in both the dip and drive. In the push jerk, the power zone is called on for the dip, drive, second dip and squat. The role of the hip is increased in each exercise.

With the push press, you will be able to drive overhead as much as 30 percent more weight than with the shoulder press. The push jerk will allow you to drive as much as 30 percent more overhead than you would with the push press.

In effect, the hip is increasingly recruited through the progression of lifts to assist the arms and shoulders in raising loads overhead. After mastering the push jerk, you will find that it will unconsciously displace the push press as your method of choice when going overhead.

The second dip on the push jerk will become lower and lower as you both master the technique and increase the load. At some point in your development, the loads will become so substantial that the upper body cannot contribute but a fraction to the movement, at which point the catch becomes very low and an increasing amount of the lift is accomplished by the overhead squat.

Common Push Press Flaw

On both the push press and jerk, the “dip” is critical to the entire movement. It may come as a surprise to some that the dip is not a relaxed fall, but an explosive dive. The stomach is held very tightly and the resultant turn around from dip to drive is sudden, explosive and violent.

Try This:

Start with 95 pounds and push press or jerk 15 straight reps, rest 30 seconds and repeat for a total of five sets of 15 reps each. Go up in weight only when you can complete all five sets with only 30 seconds rest between each and do not pause in any set.

And This:

Repetition one: shoulder press, repetition two: push press, repetition three: push jerk. Repeat until shoulder press is impossible, then continue until push press is impossible, then five more push jerks. Start with 95 pounds and go up only when the total reps exceed 30.

This article, by BSI’s co-founder, was originally published in The CrossFit Journal. While Greg Glassman no longer owns CrossFit Inc., his writings and ideas revolutionized the world of fitness, and are reproduced here.

Coach Glassman named his training methodology ‘CrossFit,’ which became a trademarked term owned by CrossFit Inc. In order to preserve his writings in their original form, references to ‘CrossFit’ remain in this article.

Download a pdf of the original article HERE.

Greg Glassman founded CrossFit, a fitness revolution. Under Glassman’s leadership there were around 4 million CrossFitters, 300,000 CrossFit coaches and 15,000 physical locations, known as affiliates, where his prescribed methodology: constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity, were practiced daily. CrossFit became known as the solution to the world’s greatest problem, chronic illness.

In 2002, he became the first person in exercise physiology to apply a scientific definition to the word fitness. As the son of an aerospace engineer, Glassman learned the principles of science at a young age. Through observations, experimentation, testing, and retesting, Glassman created a program that brought unprecedented results to his clients. He shared his methodology with the world through The CrossFit Journal and in-person seminars. Harvard Business School proclaimed that CrossFit was the world’s fastest growing business.

The business, which challenged conventional business models and financially upset the health and wellness industry, brought plenty of negative attention to Glassman and CrossFit. The company’s low carbohydrate nutrition prescription threatened the sugar industry and led to a series of lawsuits after a peer-reviewed journal falsified data claiming Glassman’s methodology caused injuries. A federal judge called it the biggest case of scientific misconduct and fraud she’d seen in all her years on the bench. After this experience Glassman developed a deep interest in the corruption of modern science for private interests. He launched CrossFit Health which mobilized 20,000 doctors who knew from their experiences with CrossFit that Glassman’s methodology prevented and cured chronic diseases. Glassman networked the doctors, exposed them to researchers in a variety of fields and encouraged them to work together and further support efforts to expose the problems in medicine and work together on preventative measures.

In 2020, Greg sold CrossFit and focused his attention on the broader issues in modern science. He’d learned from his experience in fitness that areas of study without definitions, without ways of measuring and replicating results are ripe for corruption and manipulation.

The Broken Science Initiative, aims to expose and equip anyone interested with the tools to protect themself from the ills of modern medicine and broken science at-large.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Journal Club: February 5, 2026

When number-chasing replaces treating the root cause

The iceberg beneath “normal” blood sugar numbers