By Russell Berger

America’s trust in higher education has steadily declined over the last decade. In July of 2023, Gallup published a survey showing, for the first time, a majority of respondents expressing a lack of confidence in academic institutions. While there are many reasons for this growing distrust, concerns about research integrity have been working their way into the spotlight. Harvard University seems to be leading in this regard. On the heels of President Claudine Gay’s resignation, Harvard’s Dana Farber Cancer Institute now faces allegations of data manipulation in more than 50 published papers. These papers span a twenty-year period and were authored by senior researchers serving in faculty positions at Harvard Medical School, including DFCI president Laurie Glimcher. The University is currently seeking to retract six papers and correct 31 others as part of an “ongoing review.”

The allegations are concerning. While errors are inevitable in the scientific process, some of the flagged papers (like this one) contain images that appear to have been purposefully manipulated in photoshop. But the bigger problem, and the one most likely to continue to erode the public’s trust in academic science, is the university’s response. In fact, DFCI’s handling of these allegations appears to be a form of scientific misconduct itself.

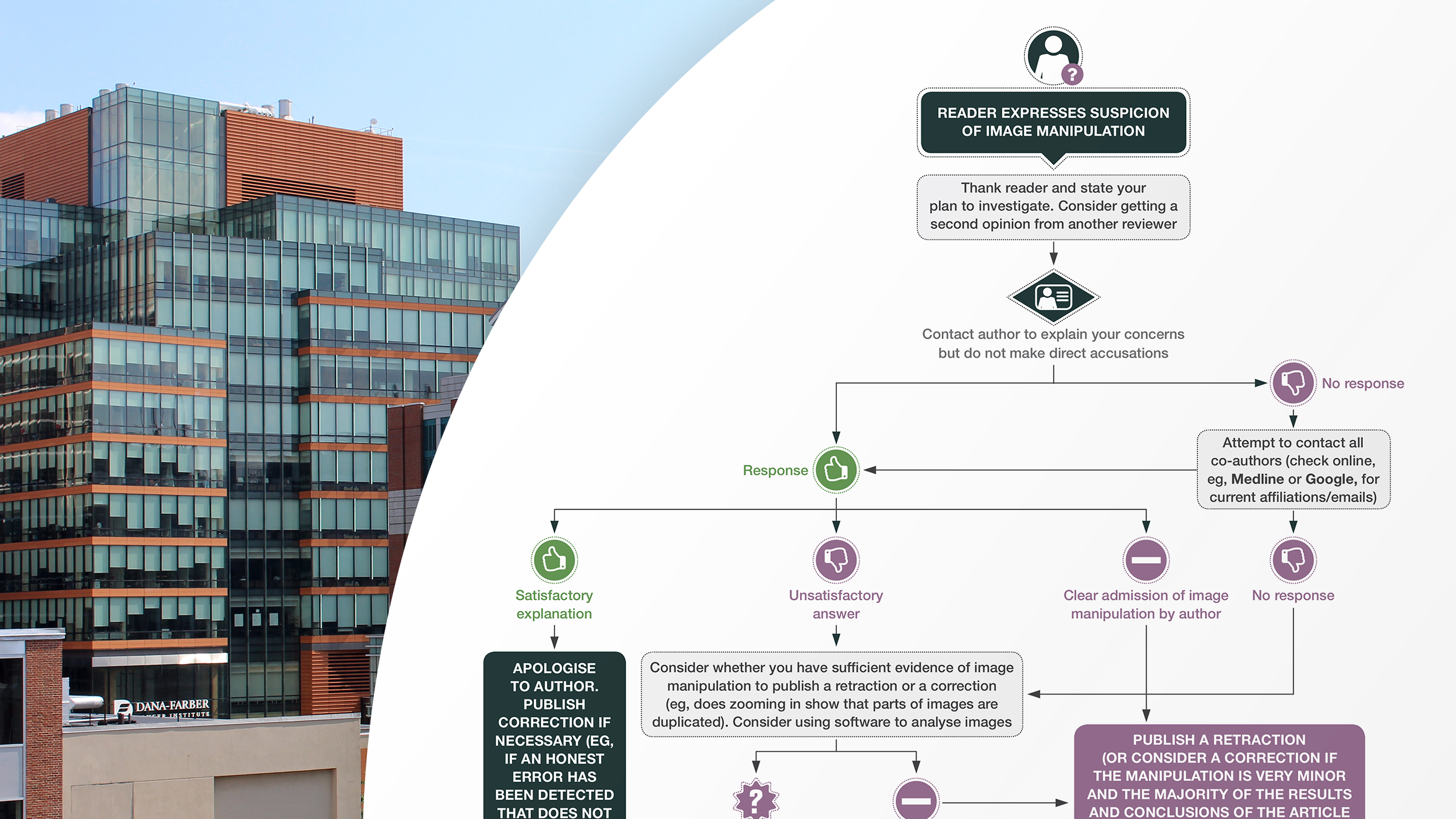

The Committee on Publication Ethics is an international organization that publishes guidance on how to evaluate claims of scientific misconduct. COPE’s flowchart for allegations of image manipulation suggests those who identify problems in a study first contact that study’s authors. Sholto David, the hobbyist data sleuth who broke the DFCI story in For Better Science, did just that. In his blog post, he claims his requests were mostly ignored, and the responses he did receive from DFCI researchers deflected blame to other authors. COPE would consider these “unsatisfactory answers” at which point they suggest contacting the author’s supervising institution. Apparently, DFCI was already aware. Barrett Rollins, who serves as the DFCI Research Integrity Office, told press “We knew about many of these papers and their allegations before the blog post.” This is where COPE’s flowchart terminates, as the burden of investigating and penalizing instances of scientific misconduct is understood to fall on the author’s supervising institution. If that organization finds evidence of misconduct, or concludes further inquiry is warranted, they may contact the Federal Office of Research Integrity to open their own investigation.

On the surface, it would seem that DFCI has responded appropriately, with Rollins continuing the institute’s review and requesting retractions and corrections as needed. But what many have failed to notice is that Rollins’ close relationship with those authoring the papers in question is a violation of the Federal Policy. Federal Research Misconduct policy. Section IV of the policy, which outlines guidelines for institutions investigating misconduct states:

“The selection of individuals to review allegations and conduct investigations who have appropriate expertise and have no unresolved conflicts of interests help to ensure fairness throughout all phases of the process.” (my emphasis)

On ORI’s website, the following guidance is given on institutional conflicts of interest arising from inquiries and investigations:

“In responding to allegations, institutions need to select committee members and experts who are free from bias and have no real or apparent conflicts of interest either with the parties involved or the subject matter. Consequently, these individuals should be free of professional, financial, personal, or other substantial ties to the accused and the complainant.”

Rollins has co-authored two of the papers under investigation, and while DFCI claims he has recused himself of reviewing those papers, he has also previously co-authored papers with three out of four of the accused researchers (Kenneth Andreson, Bill Hahn, and Irene M. Ghobrial). The only accused researcher Rollins hasn’t co-authored a paper with is DF’s President and CEO (and deciding officer) — Laurie Glimcher. Nevertheless, Rollins has worked closely with Glimcher for decades. At a DFCI event in 2022, Glimcher referred to Rollins as her “right arm, a wise counselor, a loyal friend of 30 years, and a cherished colleague.” Likewise, Rollins spoke of his fondness for DFCI and the relationships he’s established with people who work at the institute. “They are brilliant, they are kind, they are world-class leaders and they have become my friends.” In light of the ORI guidance above, Rollins should be prohibited from carrying out any investigation of these researchers. By remaining in charge of the review, Rollins has made himself judge and jury over his own professional reputation and those of his closest colleagues, a situation that makes impartiality impossible.

This is not the only concerning development in the DFCI scandal. As previously mentioned, Rollins told the Wall Street Journal DFCI was already aware of problems in these studies and has been reviewing them for over a year. But if Rollins knew of these allegations for over a year, why was nothing done about them until David’s blog post exposed the issue, after which DFCI sought retractions and corrections almost immediately? Rollins seems to be claiming that DFCI’s year-long secret investigation was set to wrap up at precisely the same time David’s blog exposed the DFCI’s problematic papers. In other words, DFCI’s swift retractions and corrections had nothing to do with getting caught, It was just a coincidence of timing. Incredulous readers might have a different take. Isn’t it potentially more likely Rollins and his colleagues were aware of the image manipulation in their papers and were content to sit on them indefinitely rather than exposing themselves to the public eye?

One possible explanation for Rollins remaining in charge of DFCI’s investigation is the legal implications that could come from a finding of scientific misconduct. Of the 58 papers identified by David as having errors or manipulated data, the National Institutes of Health has publicly available funding data for 37 of them. These 37 papers were associated with 64 different NIH funding projects totalling $49,860,264. If DFCI were to find even a fraction of these papers to be examples of scientific misconduct, it would be an admission that the institute had wasted an enormous amount of taxpayer money. More significantly, if it was discovered that manipulated research was used to support an NIH application Harvard would be open to civil, and potentially even criminal charges under the False Claims Act.

This is exactly what happened to Duke University in 2019. Whistleblowers alleged that Duke researchers used fraudulent research to support grant applications submitted to the EPA and NIH. As a result, the school was forced to settle with the Department of Justice for $112.5 million. The NIH is clear that it retains the right to recover grant funds “misspent” in this way. The legal implications of this situation may explain Rollin’s brazen defiance of conflict of interest violations. Rollins can’t afford to fully recuse himself of the misconduct investigations into DFCI because DFCI can’t afford to find misconduct. The Federal Office of Research Integrity will typically not open an investigation into an accused researcher, but reviews the investigation performed by that researcher’s supervising institution. Rollins appears to be in the position to make sure ORI does not become interested in an independent investigation of DFCI.

Based on Rollins’ public statements, this seems to be the trajectory of DFCI’s investigation. Rollins has already indicated that, while errors were made, we should not expect a pronouncement of scientific misconduct. Rollins told Science “The presence of image discrepancies in a paper is not evidence of an author’s intent to deceive,” and cautioned that “conclusion can only be drawn after a careful, fact-based examination which is an integral part of our response. Our experience is that errors are often unintentional and do not rise to the level of misconduct.”

The Federal Office of Research Integrity will typically not open an investigation into an accused researcher, but reviews the investigation performed by that researcher’s supervising institution. Rollins appears to be in the position to make sure ORI does not become interested in an independent investigation of DFCI.

Note the careful wording of his statement. Rollins is suggesting that “intent to deceive” is a part of the test determining whether or not scientific misconduct has occurred. As a research integrity officer, he undoubtedly knows that this is not true. The U.S. Federal Research Misconduct Policy, published in December of 2000, included several interactions with public comments to clarify this issue. It states:

“Several comments requested clarification regarding the level of intent that is required to be shown in order to reach a finding of research misconduct.

“Response: Under the policy, three elements must be met in order to establish a finding of research misconduct. One of these elements is a showing that the subject had the requisite level of intent to commit the misconduct. The intent element is satisfied by showing that the misconduct was committed `intentionally, or knowingly, or recklessly.’ Only one of these needs to be demonstrated in order to satisfy this element of a research misconduct finding.” (my emphasis).

In other words, an author’s intent to deceive is a sufficient but ultimately unnecessary criteria for a finding of scientific misconduct. Rollins appears to be misrepresenting this standard in his remarks to the press. Clearly, a finding of recklessness on the part of DFCI researchers should be considered. There is historical precedent for this. For example, in 2020, the Federal Office of Research Integrity found Prasadarao Nemani, Ph.D., guilty of scientific misconduct for “recklessly” reporting falsified image data in order to “falsely represent results using images from unrelated experiments in eight figures included in one published paper and four grant applications”. In another case, Frank Sauer, Ph.D. was found to have “engaged in research misconduct by intentionally, knowingly or recklessly falsifying and/or fabricating images” by “manipulating, reusing, and falsely labeling images of autoradiograms and gels to represent falsely the results of different experiments on the epigenetic regulation of gene expression.”

Given these examples, DFCI seems to have an institutional conflict of interest that would prevent them from carrying out an impartial investigation into these allegations.

The allegations of data manipulation among DFCI researchers not only casts a shadow over the institution’s research integrity but also contributes to the broader erosion of trust in academic science. The handling of these allegations, particularly Rollins’ questionable role in overseeing an investigation that involves his own papers, his boss’s papers and his close colleagues’ papers raises significant ethical concerns. The potential legal implications surrounding NIH funding of these papers underscores the need for a thorough and impartial review. As it stands, the public should have little confidence this will happen.

Russell Berger is a contributing writer to the Broken Science Initiative, with a focus on scientific misconduct. Previously, he served as an in-house investigative reporter, lecturer and corporate representative for CrossFit. His work has successfully uncovered scientific fraud and misconduct in the health sciences, both in the United States and internationally.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Metabolic Flexibility to Burn Fat, Get Stronger, and Get Healthier

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio