Handstands, hand walking, and pressing to the handstand are critical exercises to developing your athletic potential and essential components to becoming “CrossFit.”

Historically, these exercises have been collectively referred to as “hand balancing” and have been an integral part of strength and health culture since antiquity, yet today hand balancing seems to have followed the passenger pigeon to extinction.

Examining the twin questions “what has been lost by this extinction?” and “what does hand balancing offer that makes it essential?” is the aim of this month’s Journal. The answers to these questions motivate a challenge for our readers for the New Year.

The quick and obvious analysis as to hand balancing’s benefits would include improved balance and increased shoulder strength, and though accurate, ending the analysis here doesn’t speak to the singularly unique advantages to this training.

There are countless successful protocols for increasing shoulder strength and balance, but training the handstand and presses to the handstand improves proprioception and core strength in ways that other protocols cannot. Let’s examine this claim more closely.

Being upside down exposes the athlete to, what is for many, a brand new world. Psychologically, physically, and physiologically, inversion is otherworldly. We spend roughly two thirds of our life upright and one third in repose. When upside down most of us lose our breath, orientation, and composure. What this portends for an athlete upended by opponent or accident is calamitous. The difference between tripping and landing on your feet versus knocking your teeth out is profound. Gymnasts’ bike wrecks don’t look like weightlifters’.

Combat, nature, survival, and sport favor individuals who keep bodily and spatial awareness regardless of their orientation in three-space. The handstand is prerequisite to handsprings, walkovers, cartwheels, aerials, and flips, each of which will train for generally favorable outcomes to being tossed into space. The handstand is the first step to developing a catlike capacity for landing on your feet.

Standing on one’s hands also dramatically alters the normal kinetic chain required for standing on one’s feet. In the handstand, a much weaker base supports the body while simultaneously raising the body’s center of gravity a foot or more in a world turned upside down. Things don’t get more foreign.

When standing, the hip is the focus of control and leverage. When in the handstand, the focus shifts to the shoulder. This shift not only helps develop “shoulders strong as hips” but also presents a set of unique demands on the body’s core.

Many of the common motor recruitment patterns found in extending the trunk and hip while standing upright are reversed in pressing to a handstand. The enormous difficulty the beginning hand balancer encounters in bringing the hip over the shoulders and hands is due to the utter confusion of activating the extensors of the back from shoulder to hip. While upright the task of midline stabilization involves maneuvering the torso relative to the base of support—the hips and feet. While upside down the task of midline stabilization requires bringing the hips over the base of support—the shoulders and hands. The difference is profound and for most of you will be the primary obstacle to pressing to a handstand, not insufficient strength!

Similarly, a potent and largely unfamiliar recruitment of the abdominals is required of pressing to a handstand. Though highly developmental of core strength and neurological adaptations like coordination, accuracy, agility, and balance, the greater point to be made is that hand walking and pressing to the handstand are gateway movements to much of the corpus of gymnastics movements and that gymnastics training, even of rudimentary movements, has no peer for core or neurological training.

The value of training gymnastics movements for midline stabilization, torso strength, and hip control is so tremendous that it makes the bulk of what is widely conceived of as “core training,” including “Swiss” or “stability” ball training, patently silly. The Swiss ball is to core training as the BowFlex is to strength training – better than nothing.

It would be reasonable to ask “If gymnastics training, and hand balancing specifically, are so developmental, why isn’t this training modality in more common use?” Perhaps we are the wrong folks to be answering this question in that gymnastics training is essential to our model of fitness, but we cannot help but point out that the market trend for fitness has, for the past forty years, been towards less technical, strenuous, and efficacious protocols. This trend has corrupted physical training even at the university and within police and military training programs.

Though battling this trend is part of our charter, we’ve recently come to feel that we’ve not been entirely successful inspiring greater effort and commitment to our friends exploring the gymnastics realm. The difficulties motivating greater gymnastics training through the Internet and this Journal are obvious and formidable but clearly surmountable. We have a plan.

We are asking each of you to resolve to pressing to a handstand and then hand walking 100 feet within this year, 2004. Towards this end we are offering three simple floor drills that we want you to include as a warm-up for every non-pressing workout and as a “cooldown” for pressing workouts.

Here are the drills:

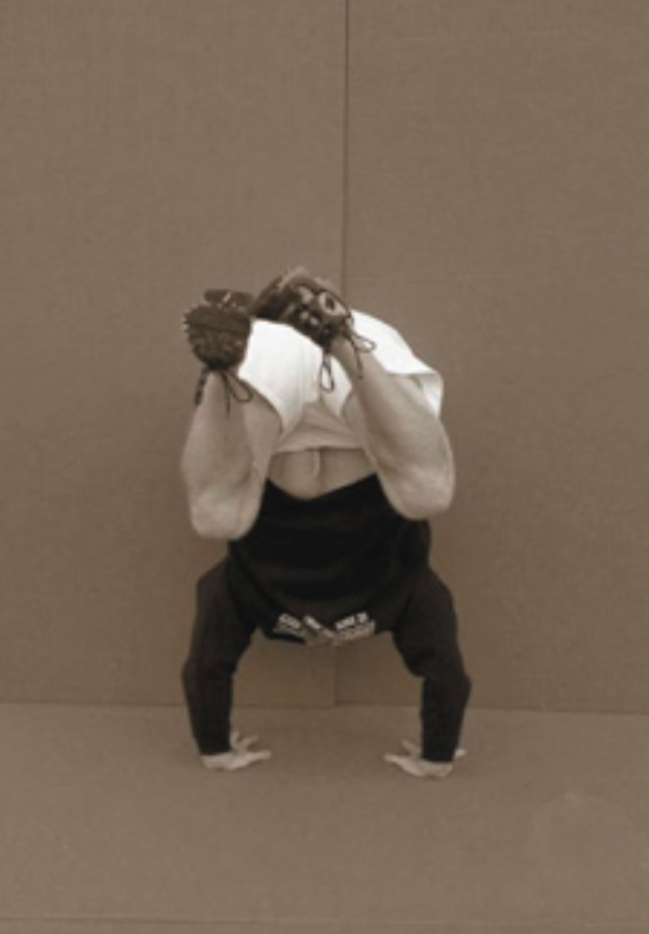

“Take-Offs”

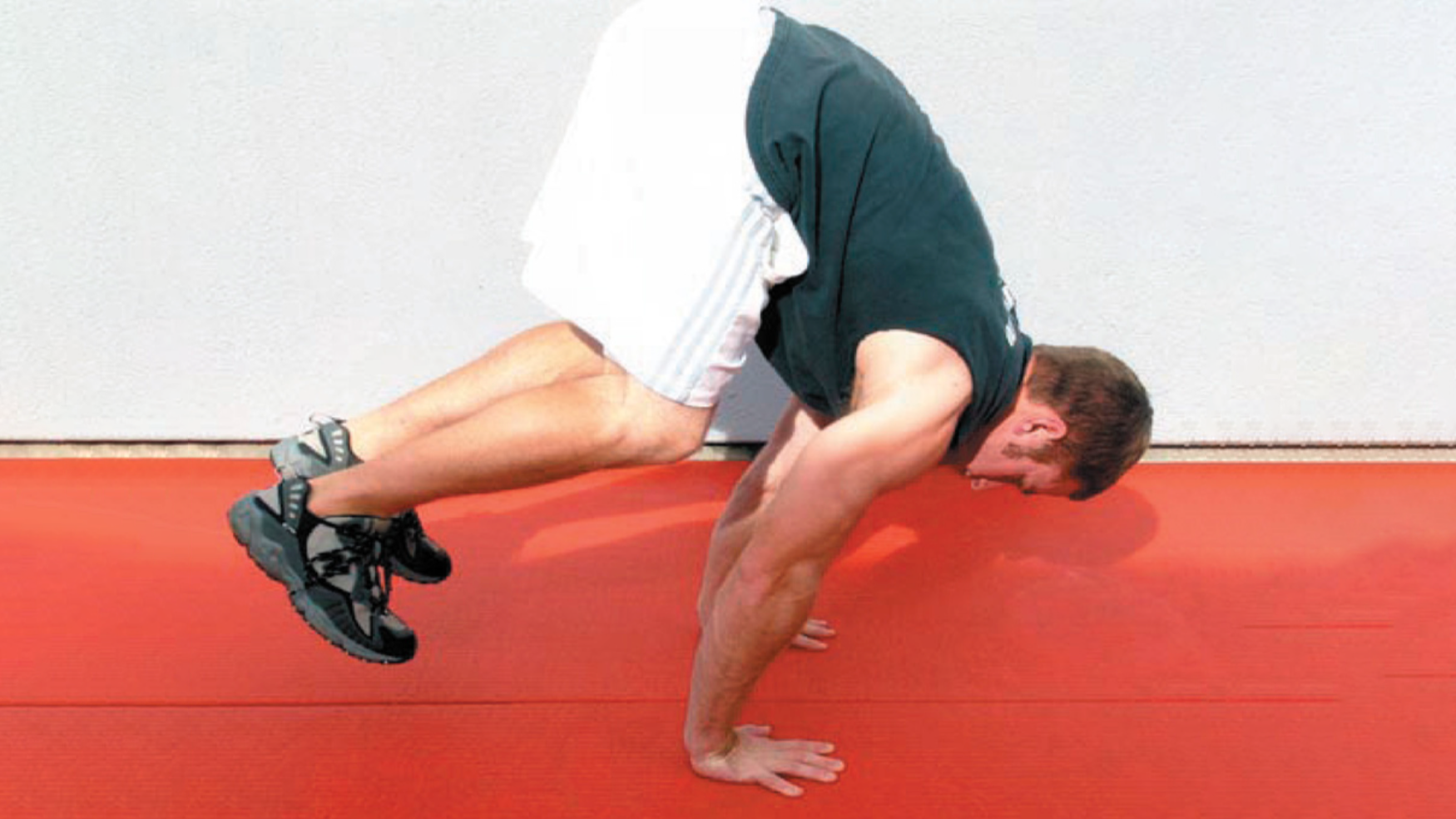

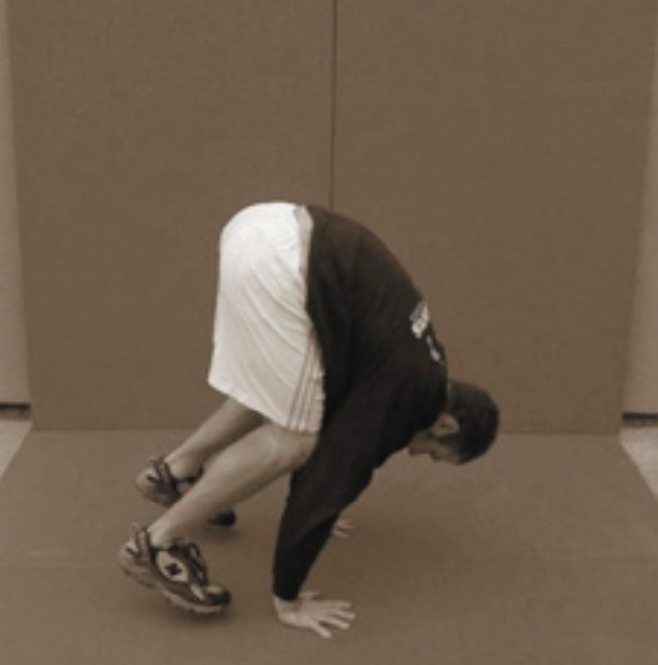

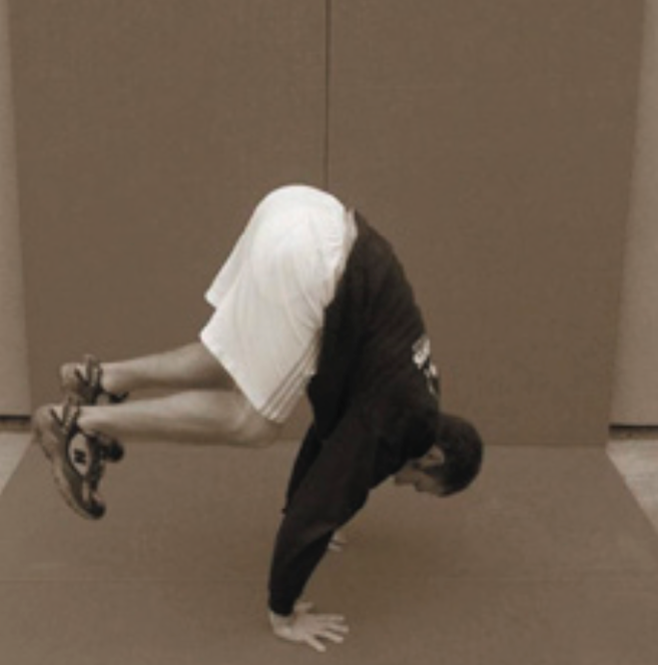

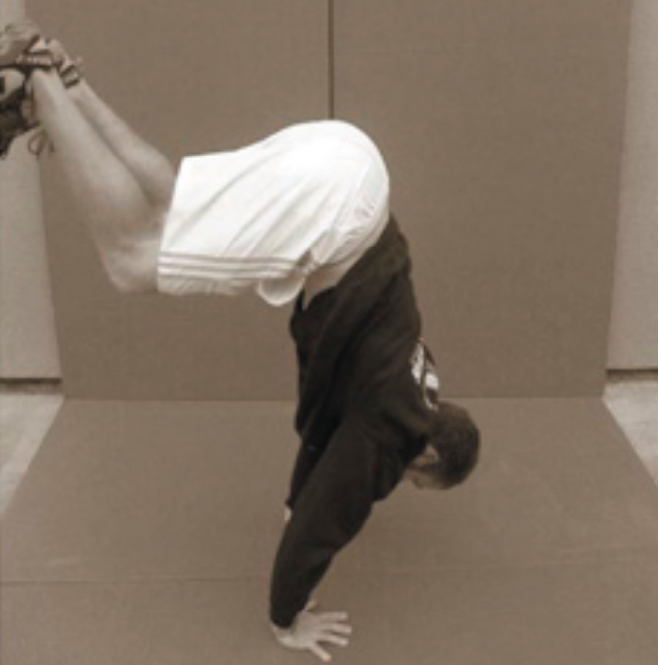

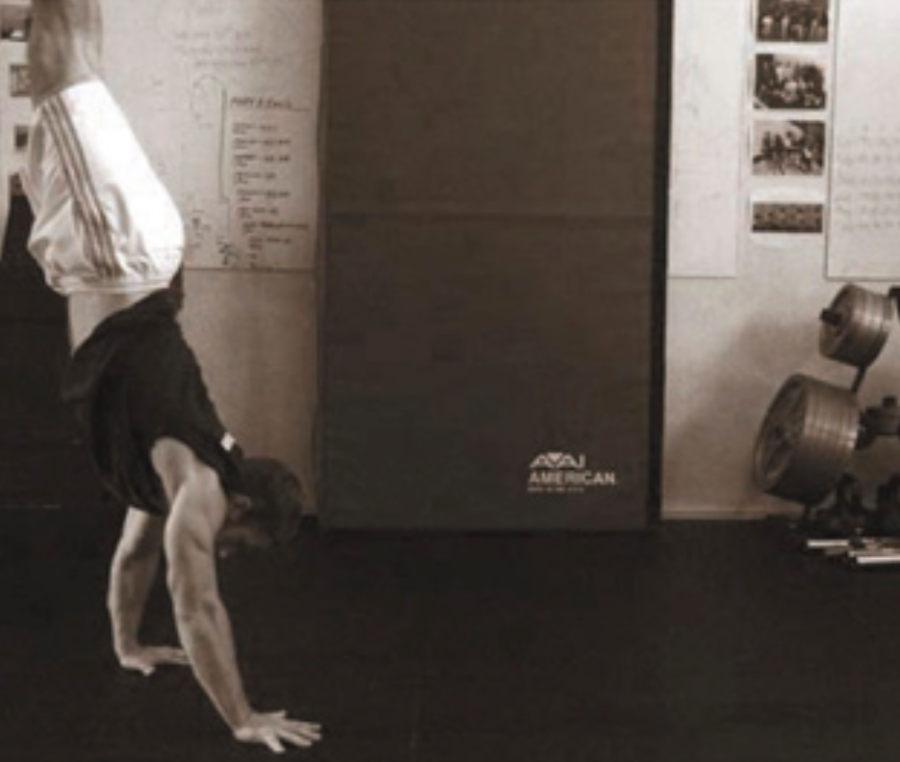

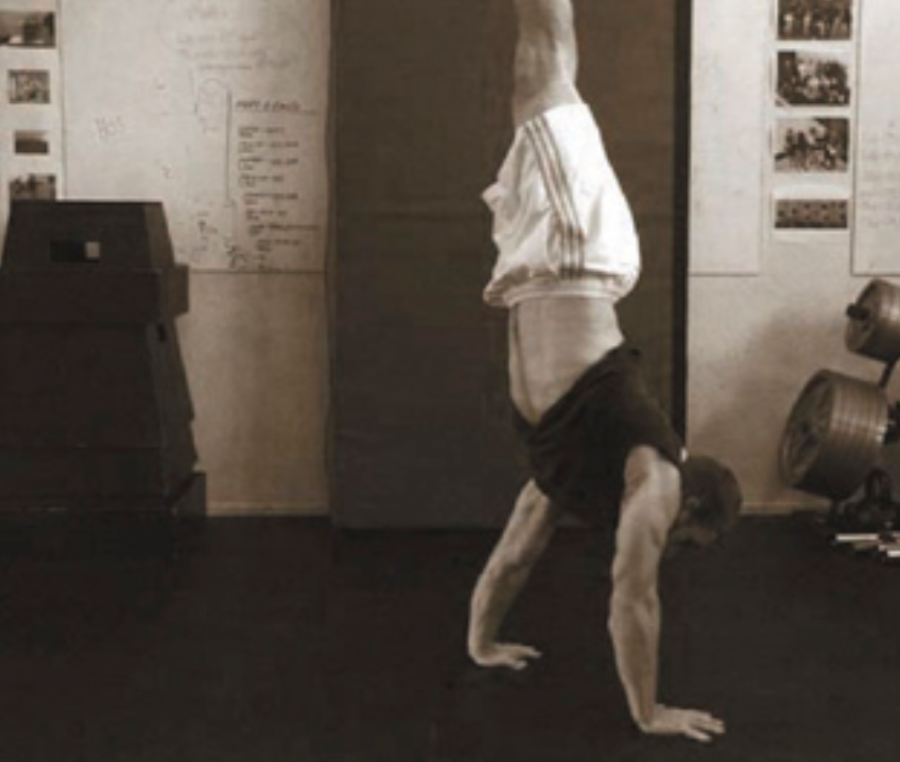

Stand with feet about shoulder width apart. Place your hands on the ground just outside and in front of your feet. In the set-up flex your arms, legs, and shoulders as little as possible while simultaneously flexing at the hips as much as possible. This position is similar to a toetouch stretch – very similar. Next, slowly lean forward while rising up on the toes and gently, slowly, shifting your weight from your feet to your hands until your feet gently lift off the ground. The challenge is to bring your hips over your hands. Do not jump or push off at all! When your feet come off the ground, lift them skyward to complete the handstand. Perform three to five takeoffs each workout.

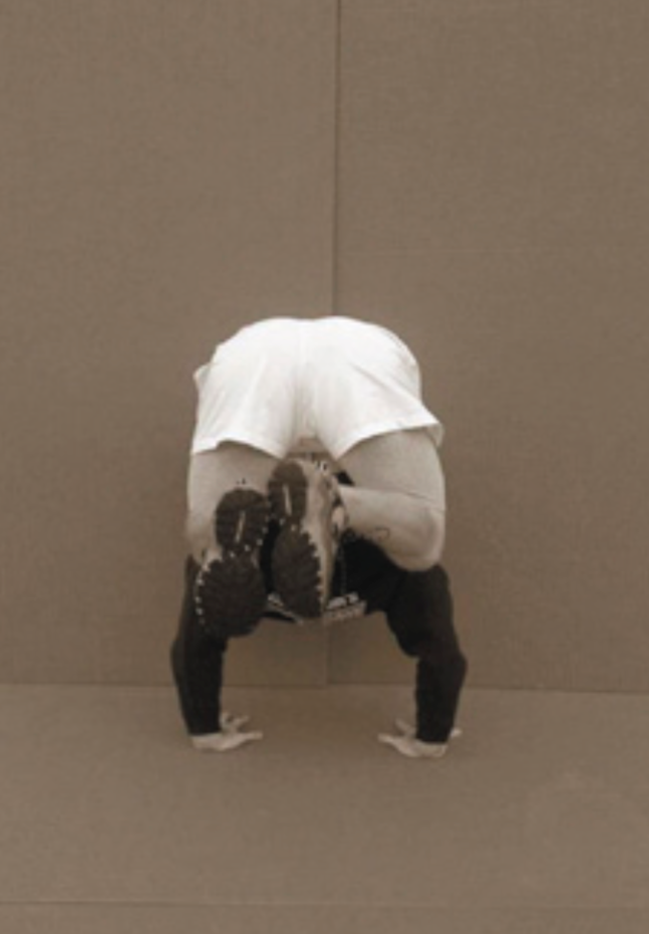

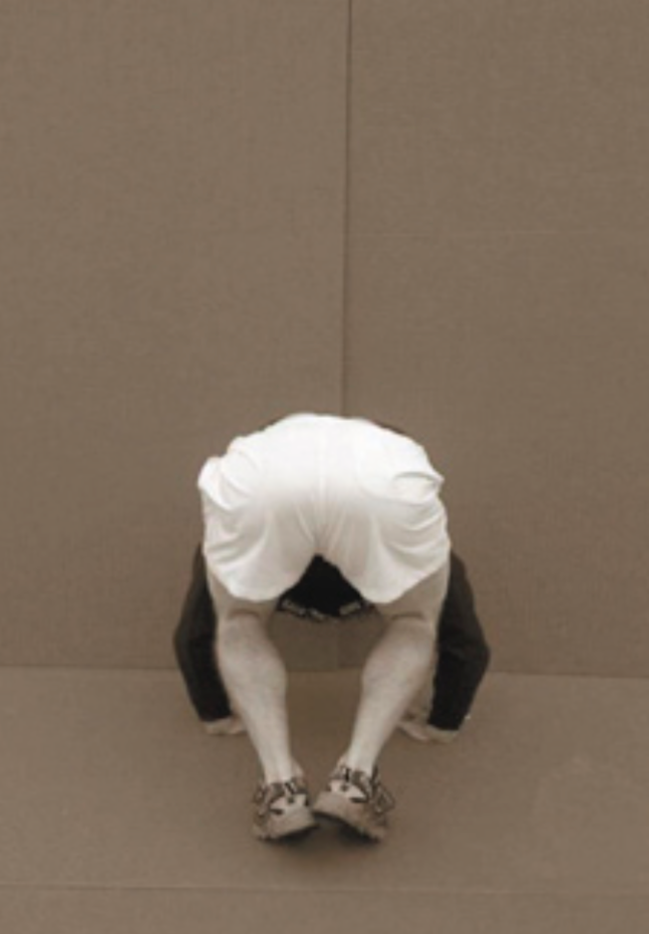

“Landings”

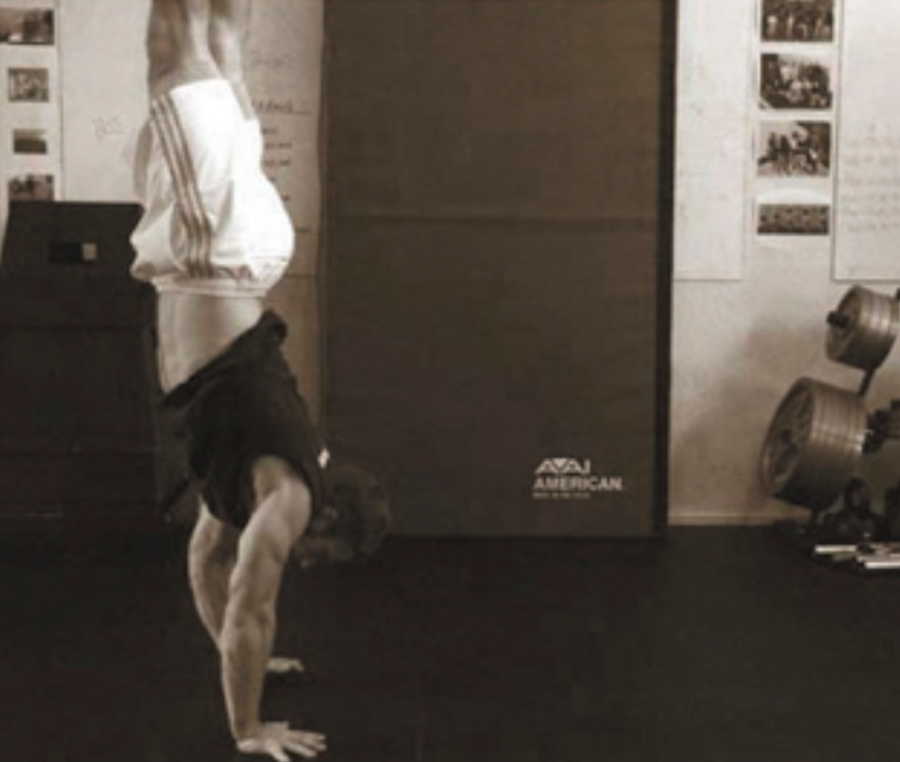

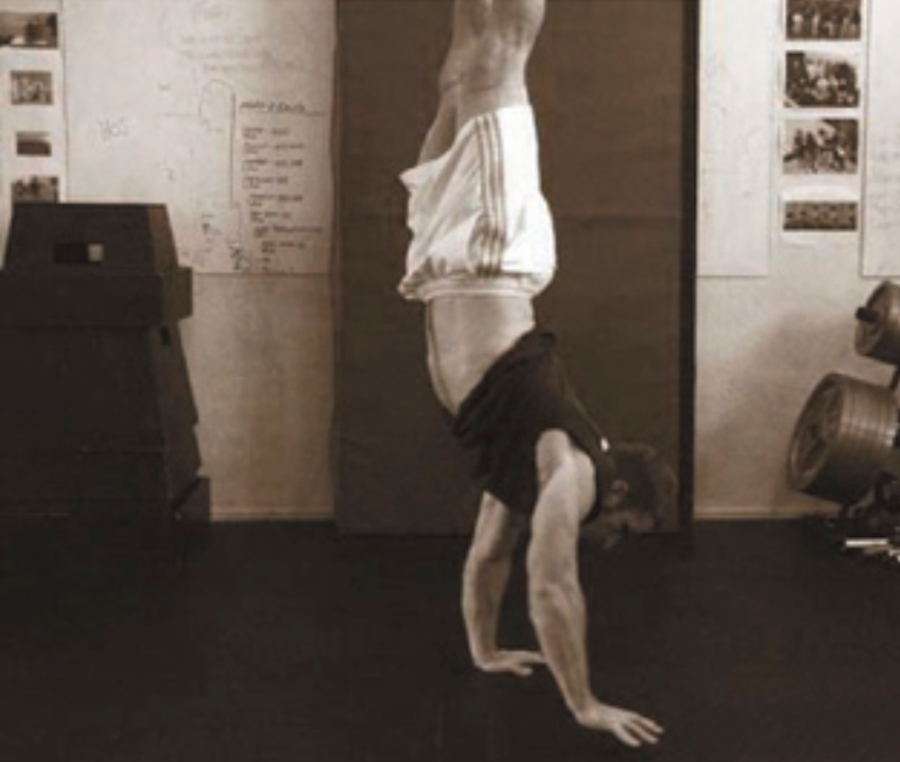

Kick or jump to the handstand and after a three second hold bring your feet towards the floor as slowly as you can. The challenge is to keep your hips over your hands as long as possible. A perfect landing settles your feet between your hands gently and slowly, and may take years to master. Perform three to five landings each workout.

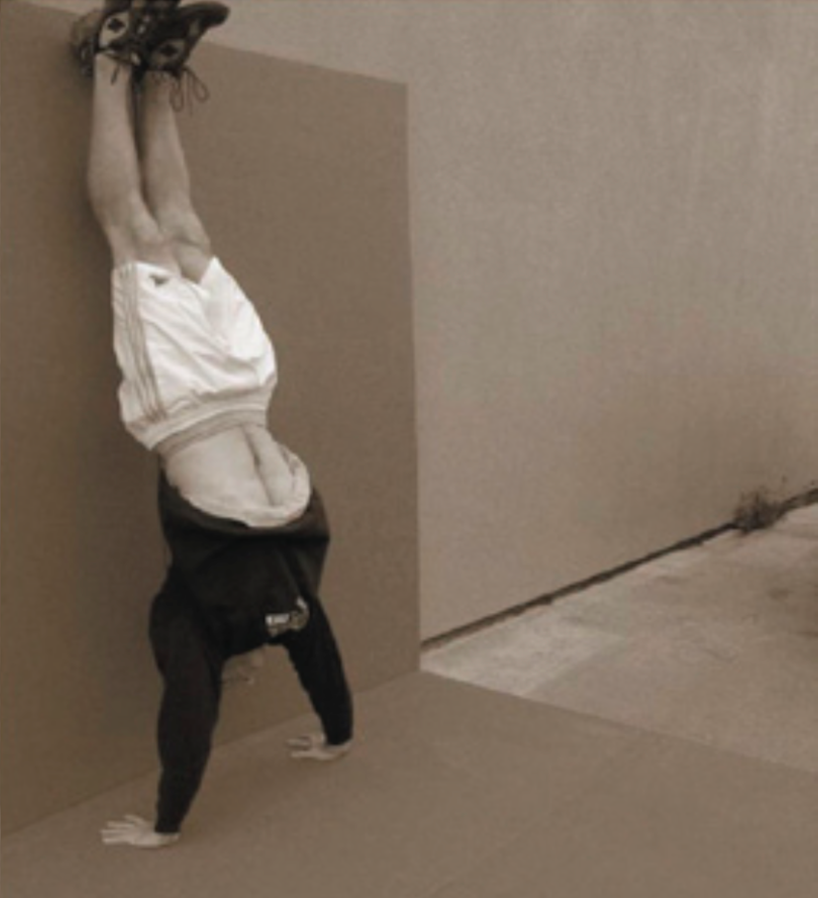

“Kick-Ups”

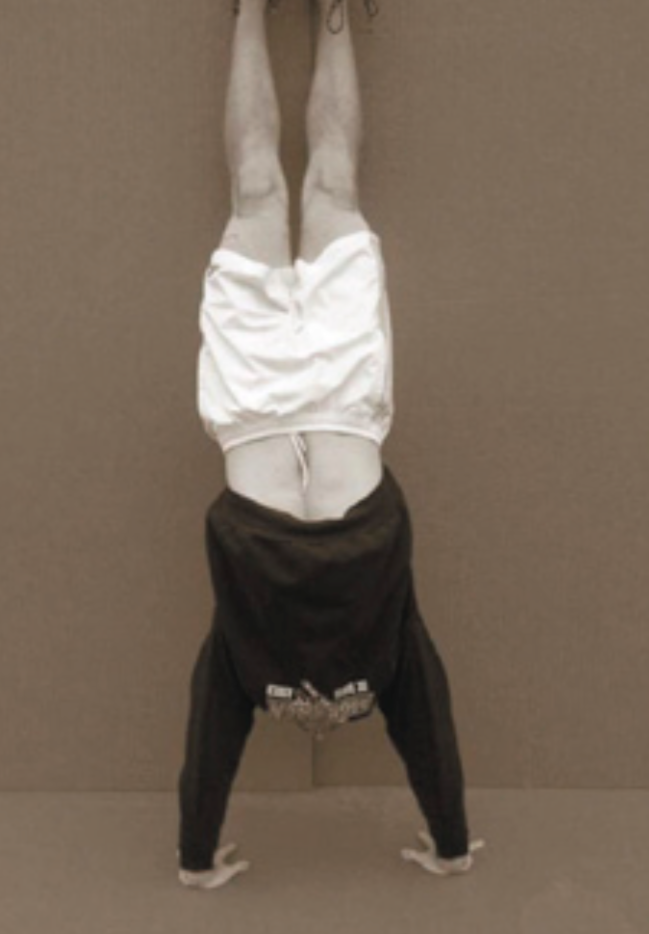

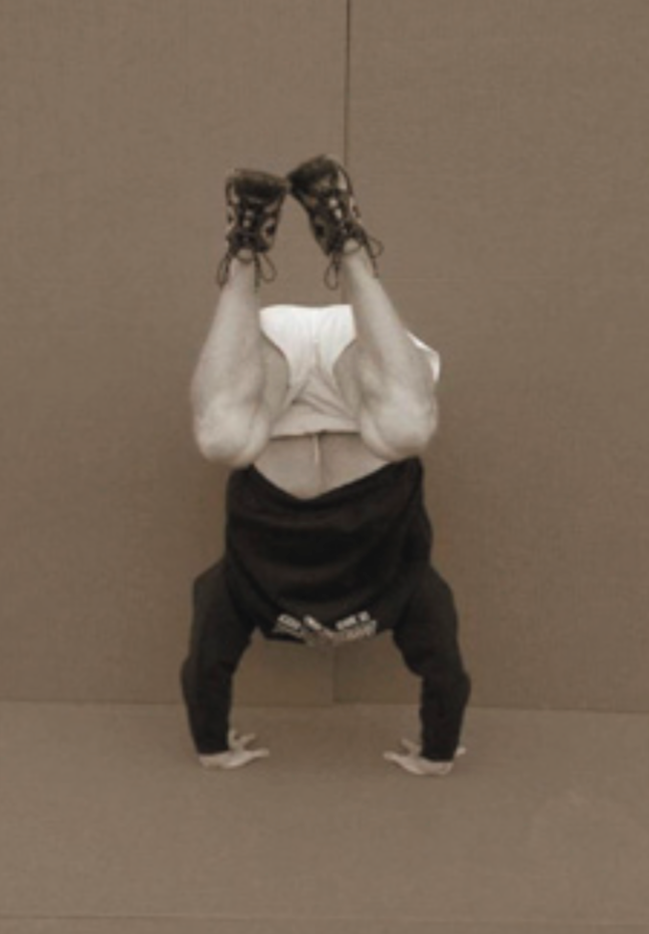

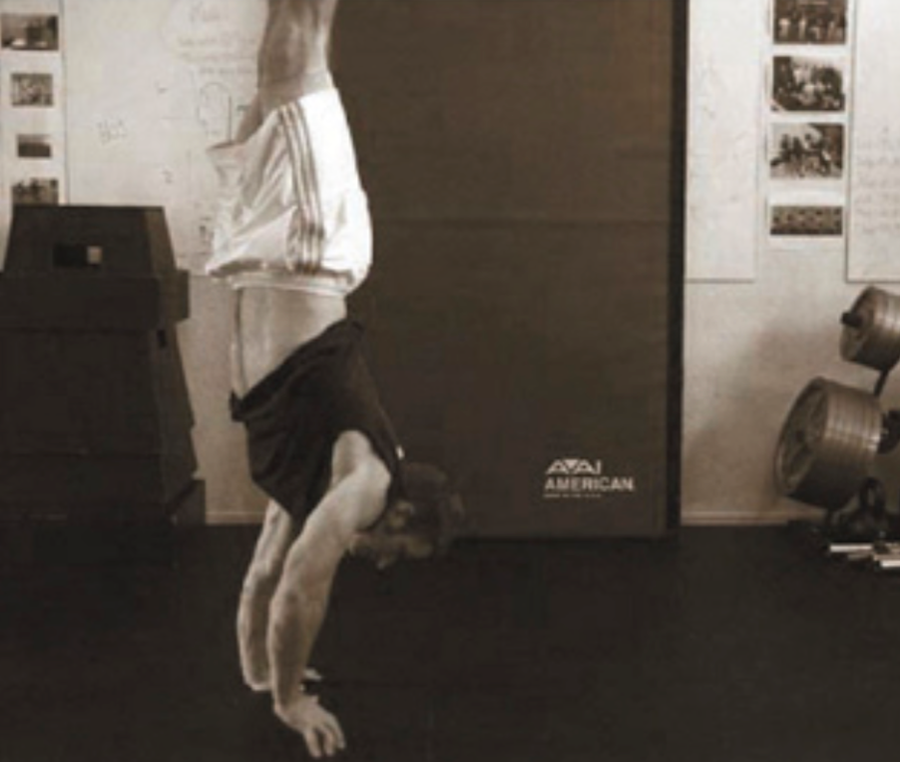

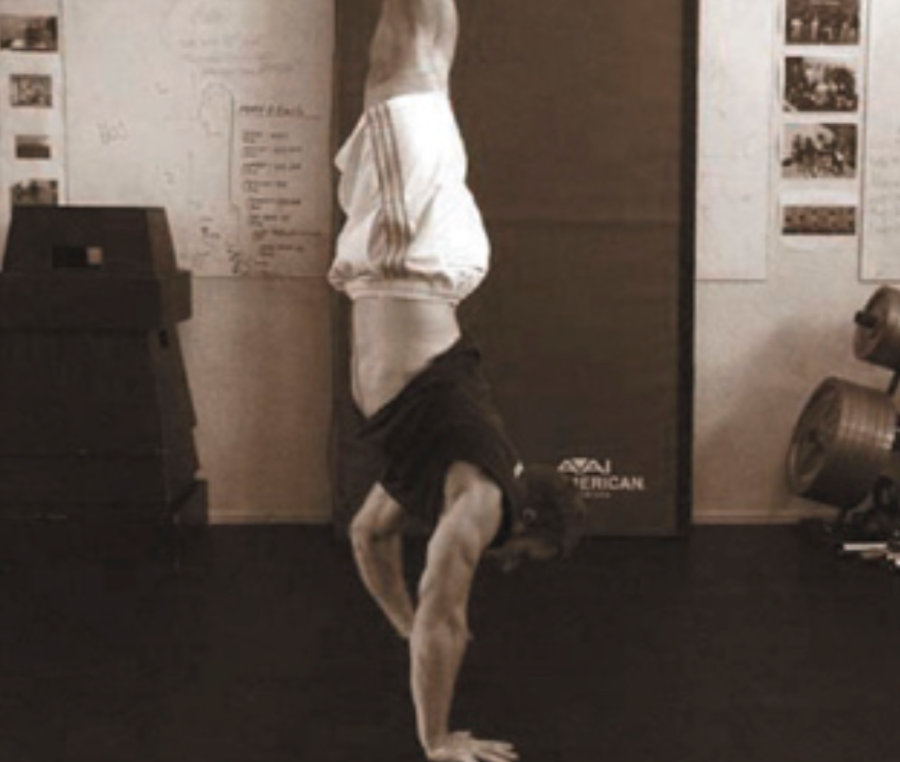

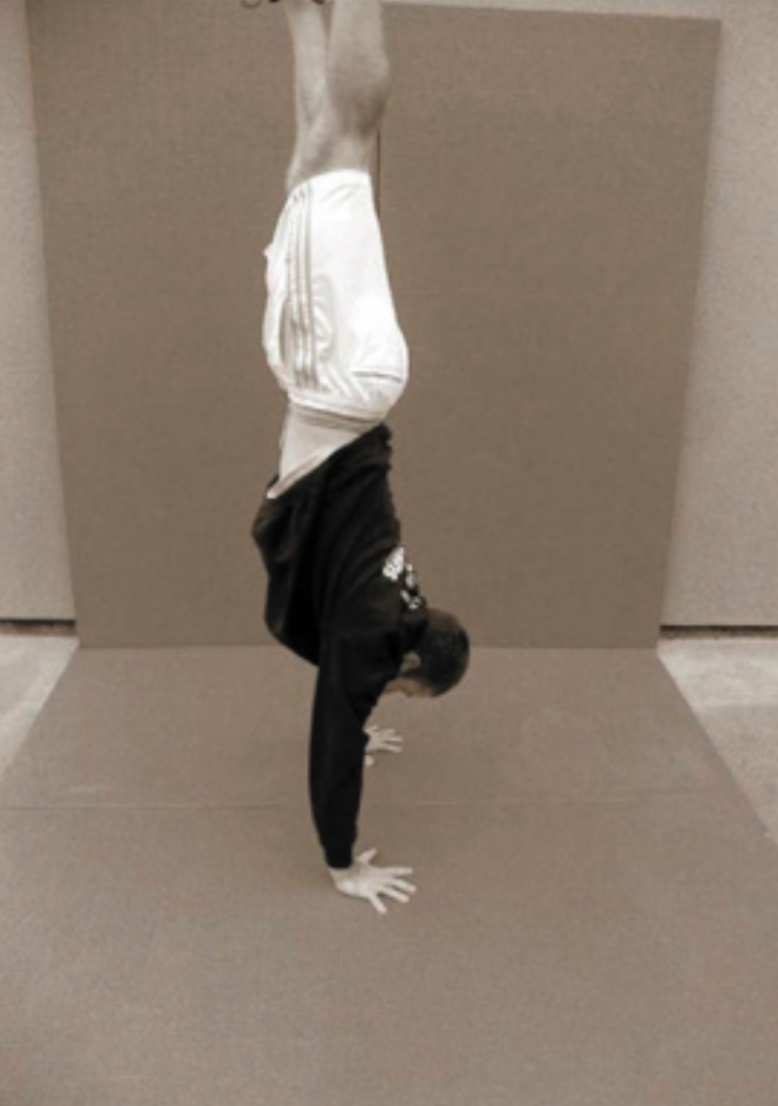

Kick or jump to the handstand against a wall. The first time up hold the handstand as long as you can, up to one minute, flirting with the balance point by gently pushing off the wall with your heels. For the second handstand you’ll try to walk on your hands. Take little steps and note your distance covered. Alternate these efforts until two of each, for a total of four, have been performed each workout.

We’re recommending that these drills be performed in this order and after a CrossFit-like warm-up of a circuit of squats, pull-ups, push-ups, or related calisthenic movements.

It’s O.K. if your take-offs don’t takeoff or if your landings are more like crashes; do them anyway. If these drills are seemingly impossible, don’t let that psych you out. Nothing about your difficulties suggests their inappropriateness for you.

For each exercise, in the set-up, place your hands shoulder-width apart with the fingers spread and the hands pointed forward. Keep your eyes on a spot between your hands.

The take-off is a genuine press to a handstand – the first and easiest. When it’s mastered, you’ll learn to press to a handstand with perfectly straight arms and legs, the “stiff-stiff” press. After the stiff-stiff press you’ll learn the straight body (hips and legs), bent arm press – the “hollow back” press. Finally, comes the ultimate press on the floor, parallel bars, or rings, the straight body, straight arm press – the “planche press.”

Landings teach control and work the “negative” or eccentric portion of pressing to a handstand. Most gymnastics strength moves and holds are learned, in large part, by working the negative until you can slow the movement to an eventual stop. This comes long before the concentric portion of a movement is possible. The iron cross, planches, and other scales and levers have all been trained successfully this way forever.

The kick-ups give you more upside down time and, of course, expose you to hand walking and general competence at moving, balancing, and controlling your movements while inverted. Measure your progress by either steps taken or distance traveled – both will work. The goal is 100 feet.

Each of these drills should be practiced initially against a wall. As your confidence, balance, flexibility, and strength improve, you’ll want to move these drills away from the wall and into open space. The fear of falling over backwards is strong but you can manage it by learning to bail out cleanly.

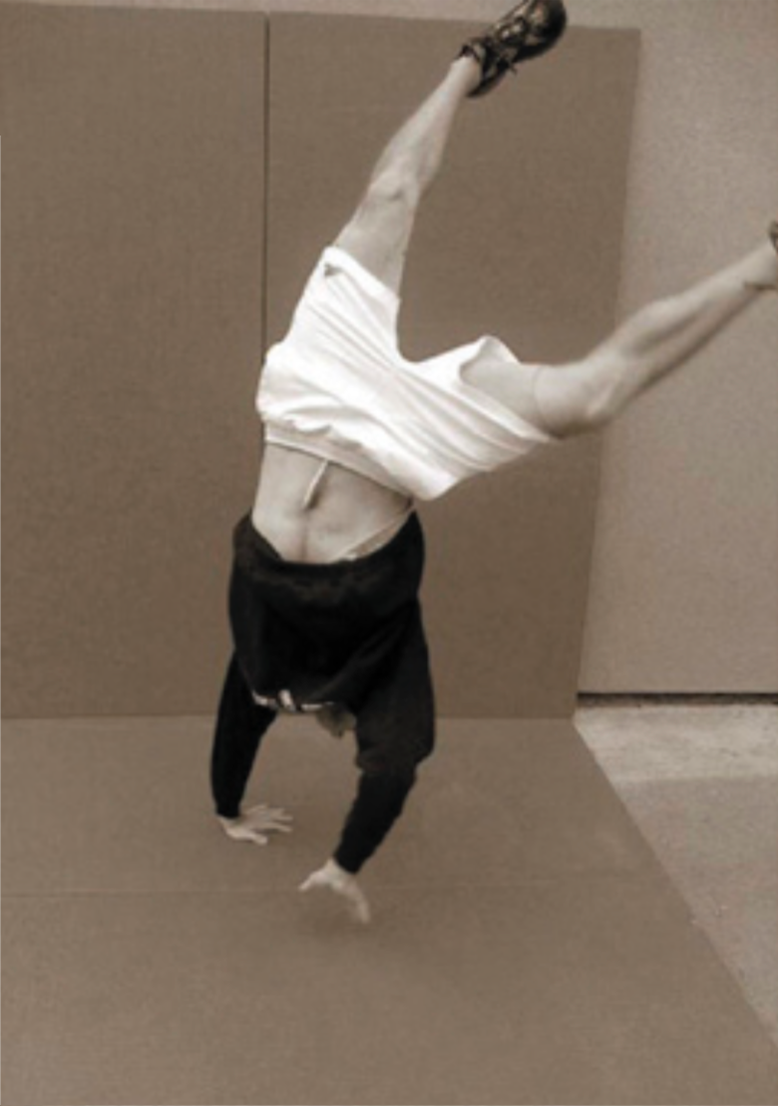

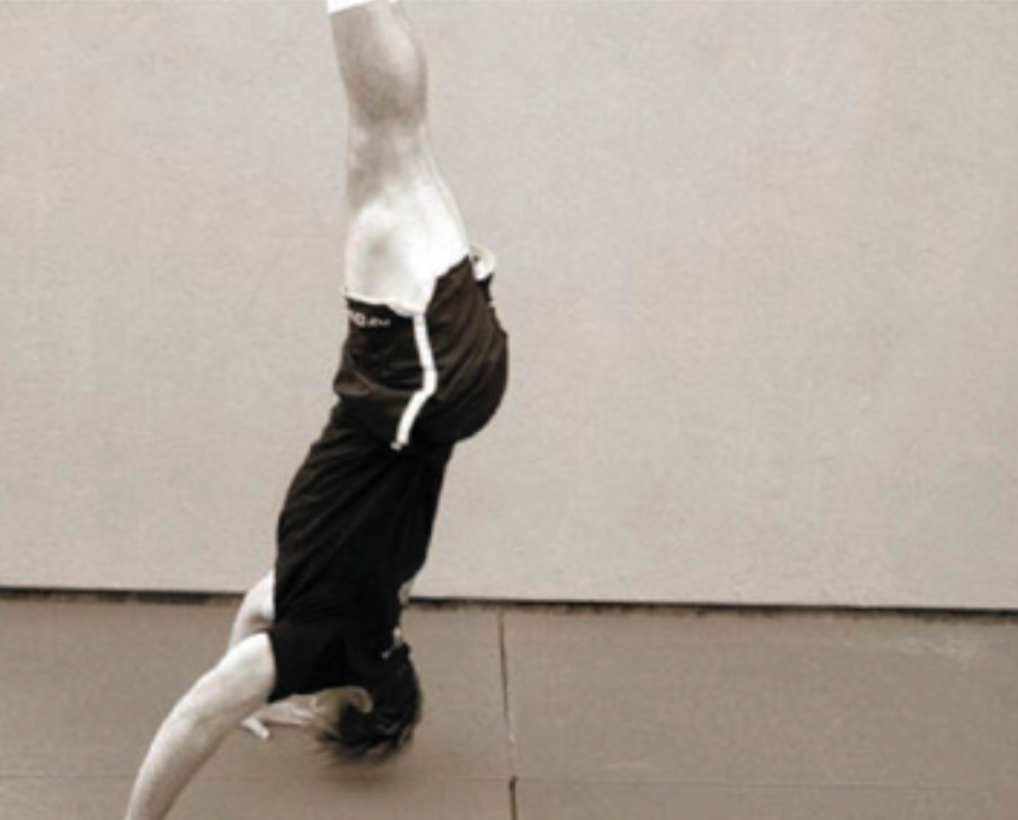

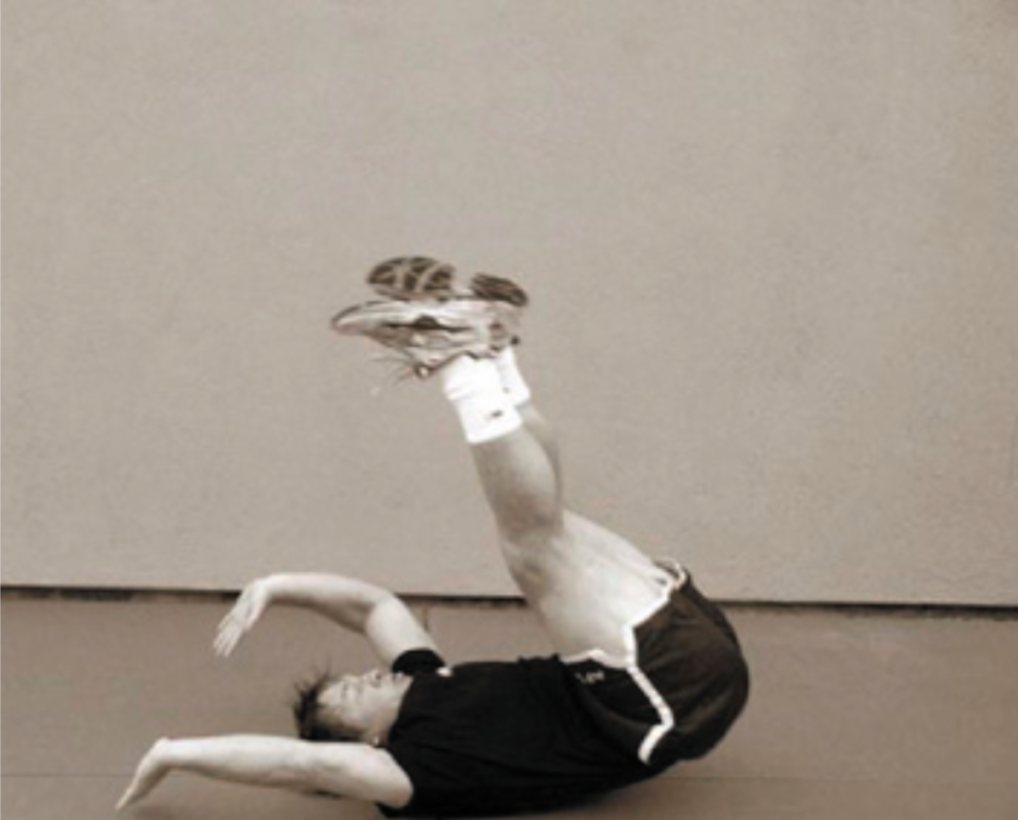

There are two common methods for bailing out. The first is to make a ¼ – ½ turn while falling and landing on your feet. The second method is to tuck your chin to your chest, round your back, and let your arms gently lower you to the ground where you’ll roll to a seated position. Practice and master both methods on mats – both skills are also critical to later movements.

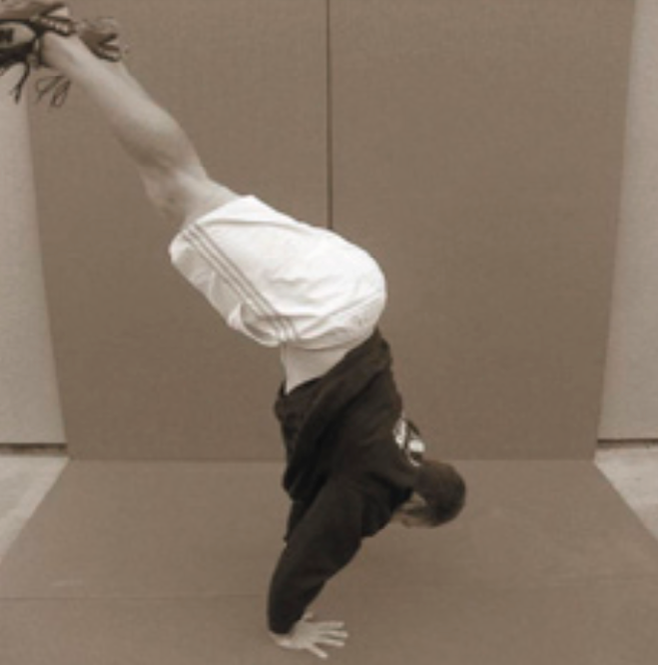

Bail-out method 1

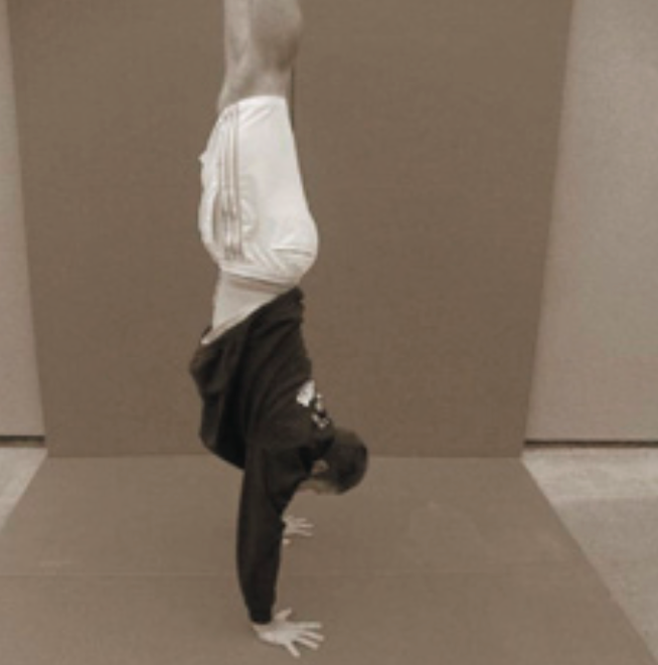

Bail-out method 2

Resources

- Rings – Methods, Ideas, Curiosities, History, Ivan Cuk, PhD and Dr. Istvan Karacsony

- Jeff Gothard, Hand Balancing and Feats with Bodyweight, MILO March 2000, Volume 7 – Number 4

- Jeff Gothard, Hand Balancing (Part II): Presses and Pirouettes, MILO June 2000, Volume 8 – Number 1

- Jeff Gothard, Hand Balancing (Part III): Pressing Matters, MILO September 2000, Volume 8 – Number 2

- Jeff Gothard, Hand Balancing (Part IV): Putting It all Together, MILO December 2000, Volume 8 – Number 3

- American Gymnast, Parallette Training Guide

This article, by BSI’s co-founder, was originally published in The CrossFit Journal. While Greg Glassman no longer owns CrossFit Inc., his writings and ideas revolutionized the world of fitness, and are reproduced here.

Coach Glassman named his training methodology ‘CrossFit,’ which became a trademarked term owned by CrossFit Inc. In order to preserve his writings in their original form, references to ‘CrossFit’ remain in this article.

Greg Glassman founded CrossFit, a fitness revolution. Under Glassman’s leadership there were around 4 million CrossFitters, 300,000 CrossFit coaches and 15,000 physical locations, known as affiliates, where his prescribed methodology: constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity, were practiced daily. CrossFit became known as the solution to the world’s greatest problem, chronic illness.

In 2002, he became the first person in exercise physiology to apply a scientific definition to the word fitness. As the son of an aerospace engineer, Glassman learned the principles of science at a young age. Through observations, experimentation, testing, and retesting, Glassman created a program that brought unprecedented results to his clients. He shared his methodology with the world through The CrossFit Journal and in-person seminars. Harvard Business School proclaimed that CrossFit was the world’s fastest growing business.

The business, which challenged conventional business models and financially upset the health and wellness industry, brought plenty of negative attention to Glassman and CrossFit. The company’s low carbohydrate nutrition prescription threatened the sugar industry and led to a series of lawsuits after a peer-reviewed journal falsified data claiming Glassman’s methodology caused injuries. A federal judge called it the biggest case of scientific misconduct and fraud she’d seen in all her years on the bench. After this experience Glassman developed a deep interest in the corruption of modern science for private interests. He launched CrossFit Health which mobilized 20,000 doctors who knew from their experiences with CrossFit that Glassman’s methodology prevented and cured chronic diseases. Glassman networked the doctors, exposed them to researchers in a variety of fields and encouraged them to work together and further support efforts to expose the problems in medicine and work together on preventative measures.

In 2020, Greg sold CrossFit and focused his attention on the broader issues in modern science. He’d learned from his experience in fitness that areas of study without definitions, without ways of measuring and replicating results are ripe for corruption and manipulation.

The Broken Science Initiative, aims to expose and equip anyone interested with the tools to protect themself from the ills of modern medicine and broken science at-large.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio

Maintaining quality of life and preventing pain as we age.