By William Briggs

A new study came out that claimed intermittent fasting is bad for you. This shocked a lot of people. Here’s one of the hot headlines: “8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death“.

Ninety one percent? Dude. That’s a lot. Makes it sound like skipping a meal could kill you.

Intermittent fasting is the idea that you group your daily meals into some short period of time, typically something like over eight hours or less. Many have found this to produce a range of health benefits, including Yours Truly. At the least it inculcates discipline, a virtue sorely needed in our culture.

Here are the “research highlights” from the press release:

- A study of over 20,000 adults found that those who followed an 8-hour time-restricted eating schedule, a type of intermittent fasting, had a 91% higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

- People with heart disease or cancer also had an increased risk of cardiovascular death.

- Compared with a standard schedule of eating across 12-16 hours per day, limiting food intake to less than 8 hours per day was not associated with living longer.

This research was presented at a meeting of American Heart Association as a poster, which is online here. It’s all we have to go on, since there is not (at this time of writing, anyway) a paper to accompany it.

The authors looked back at data collected in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) study, which ran from 2003 to 2019. It was not an experiment to test intermittent fasting.

NHANES relied on self-reported diet questions. Like the time spacing between meals. Those who reported eating meals over periods of less than eight hours a day likely did not fast each and every day. After all, sometimes that cupcake looks too appealing. So there is some substantial uncertainty here.

That, plus people’s memories are not always reliable about what and when they ate. Indeed, they are notoriously unreliable with their reporting.

… people’s memories are not always reliable about what and when they ate. Indeed, they are notoriously unreliable with their reporting.

Do the authors of the poster “Association of 8-Hour Time-Restricted Eating with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality” account for these great uncertainties? If they did, they didn’t tell us. And likely they did not. Most researchers don’t.

The authors broke up the self-reported times of daily meals into five buckets: less than 8 hours, between 8 and 10, between 10 and 12, between 12 and 16, and greater than 16 hours (essentially eating all day long). They called the 12 to 16 hour bucket the reference group, and calculated statistics with respect to that. The less than 8 hour group is the one that generated the hot headlines.

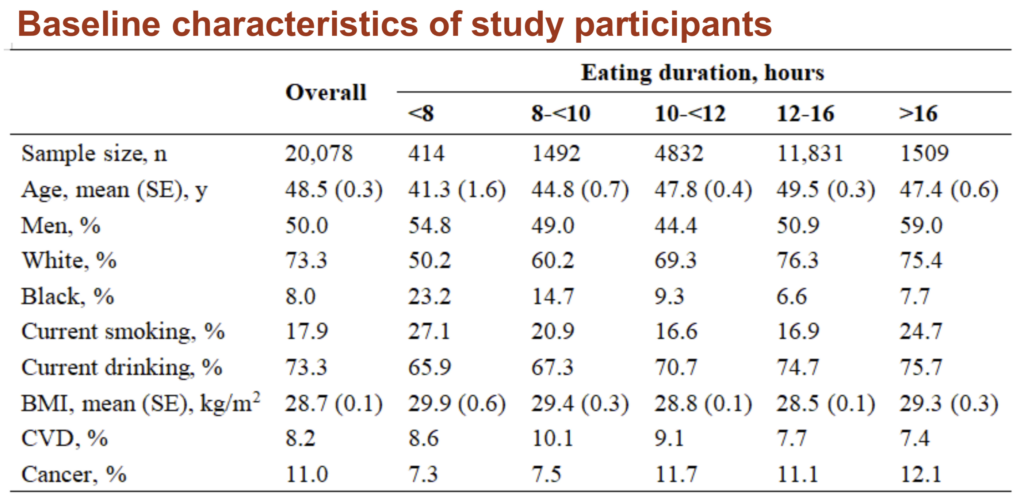

Here’s a table of the baseline characteristics of the buckets, which reveals something interesting:

First, the eight-hour group was the smallest, so it would have the greatest uncertainty.

Second, and more interesting, it had by far the most blacks at 23.3%; whereas the reference group (12-16 hours) only had 6.6%. This is important because blacks suffer from cardiovascular diseases at rates much greater than whites. One prominent source says “47% of Black adults have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, compared with 36% of white adults.”

Which means the obvious: that the racial imbalance of the time buckets could account for the headline-generating results.

Adding weight (ahem) to this possibility is that the 8 hour group had the highest average BMI: 29.9 vs the 28.5 in the reference group. The fatter you are, the greater the chance for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Lastly, there were more smokers in the 8 hour group: 27.1% vs 16.9%. Another whopping difference.

Lastly, there were more smokers in the 8 hour group: 27.1% vs 16.9%. Another whopping difference.

The authors used a type of regression called Cox proportional hazards. They say they ‘control’ for things like age, race, smoking, and BMI. But that word doesn’t mean what you think it means; it is one of several unfortunate words (like ‘significance’) that litter statistics and give the false impression that certainty is greater than it is.

Here, ‘control’ says the authors included these measures in the model along with time groups. It is not anything like real control, a key weakness of regressions that most forget. The racial and other imbalances of the sample can’t be wholly fixed by this kind of ‘control.’

Finally, the results.

There were no differences in all-cause mortality, in the regressions, between any of the time groups. Meaning the people in the intermittent fasting 8 hour group did not die at faster rates. Same for deaths in those people who already had CVD or cancer. No real differences. We don’t know what the raw counts were: we just see model output.

The same no signal was found for cancer mortality. No real differences in deaths for any time group.

The only signal in the model was for cardiovascular deaths. There, people in the 8-hour group had slightly—and it was only very slightly—larger hazard ratios than the reference group.

Does this mean the 8-hour group had worse outcomes because of fasting? Maybe. But the differences could just as easily be due to race, fatness, and smoking. And they almost certainly are, given the numbers we’ve seen. Especially since we haven’t even considered how self-report plays into this.

The press release included this gem:

“We were surprised to find that people who followed an 8-hour, time-restricted eating schedule were more likely to die from cardiovascular disease. Even though this type of diet has been popular due to its potential short-term benefits, our research clearly shows that, compared with a typical eating time range of 12-16 hours per day, a shorter eating duration was not associated with living longer,” Zhong said.

His findings went smack against massive contrary evidence, which surprised him. But not enough for him to question the modeling techniques he used.

Yet again, classical statistical procedures generate more certainty than is warranted.

I am a wholly independent writer, statistician, scientist and consultant. Previously a Professor at the Cornell Medical School, a Statistician at DoubleClick in its infancy, a Meteorologist with the National Weather Service, and an Electronic Cryptologist with the US Air Force (the only title I ever cared for was Staff Sergeant Briggs).

My PhD is in Mathematical Statistics: I am now an Uncertainty Philosopher, Epistemologist, Probability Puzzler, and Unmasker of Over-Certainty. My MS is in Atmospheric Physics, and Bachelors is in Meteorology & Math.

Author of Uncertainty: The Soul of Modeling, Probability & Statistics, a book which calls for a complete and fundamental change in the philosophy and practice of probability & statistics; author of two other books and dozens of works in fields of statistics, medicine, philosophy, meteorology and climatology, solar physics, and energy use appearing in both professional and popular outlets. Full CV (pdf updated rarely).

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life

The brain is built on fat—so why are we afraid to eat it?