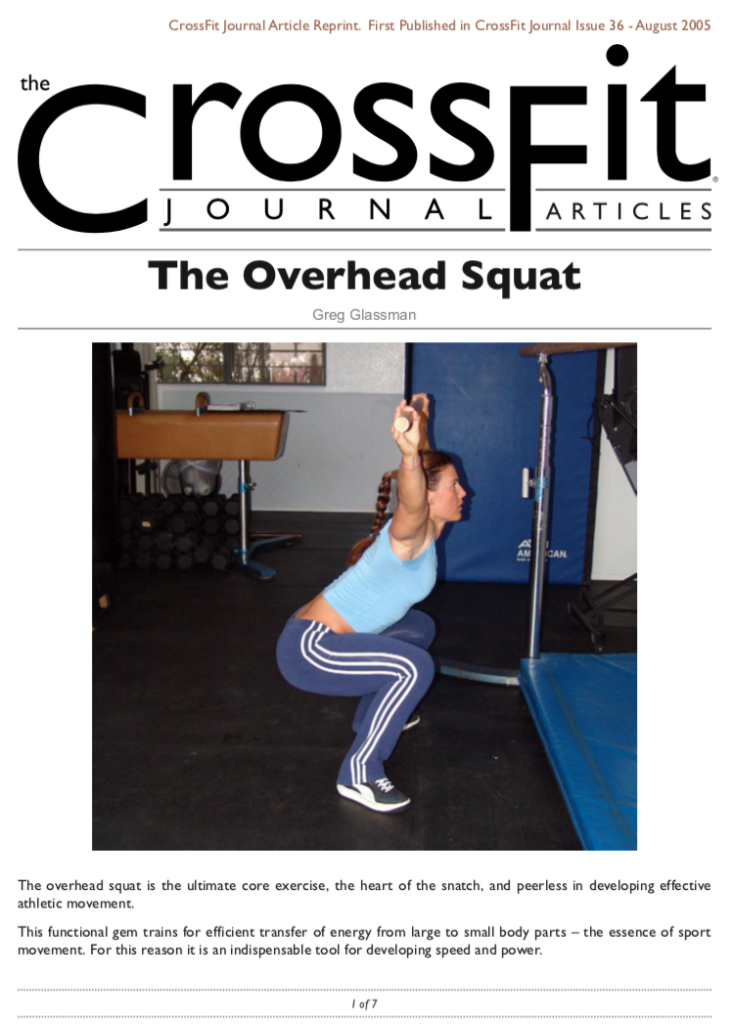

The overhead squat is the ultimate core exercise, the heart of the snatch and peerless in developing effective athletic movement.

This functional gem trains for efficient transfer of energy from large to small body parts—the essence of sport movement. For this reason it is an indispensable tool for developing speed and power.

The overhead squat is the ultimate core exercise, the heart of the snatch and peerless in developing effective athletic movement.

This functional gem trains for efficient transfer of energy from large to small body parts—the essence of sport movement. For this reason it is an indispensable tool for developing speed and power.

The overhead squat also demands and develops functional flexibility, and similarly develops the squat by amplifying and cruelly punishing faults in squat posture, movement and stability.

The overhead squat is to midline control, stability and balance what the clean and snatch are to power—unsurpassed.

Ironically, the overhead squat is exceedingly simple yet universally nettlesome for beginners. There are three common obstacles to learning the overhead squat. The first is the scarcity of skilled instruction; outside of the Olympic lifting community most instruction on the overhead squat is laughably, horribly wrong—dead wrong. The second is a weak squat—you need to have a rock-solid squat to learn the overhead squat. We strongly recommend you review our December 2002 issue on squatting before attempting the overhead squat; you could save yourself a lot of time in the long run. The third obstacle is starting with too much weight—you haven't a snowball's chance in hell of learning the overhead squat with a bar. You'll need to use a length of dowel or plastic PVC pipe; use anything over five pounds to learn this move and your overhead squat will be stillborn.

Here is our seven-step process for learning the overhead squat:

Step 1

Start only when you have a strong squat and use a dowel or PVC pipe, not a weight. You should be able to maintain a rock-bottom squat with your back arched, head and eyes forward, and body weight predominantly on your heels for several minutes as a prerequisite to the overhead squat. Even a 15-pound training bar is way too heavy to learn the overhead squat.

Step 2

Learn locked-arm “dislocates” or “pass-throughs” with the dowel. You want to be able to move the dowel nearly 360 degrees starting with the dowel down and at arm’s length in front of your body and then move it in a wide arc until it comes to rest down and behind you without so much as slightly bending your arms at any point in its travel. Start with a grip wide enough to easily pass through, and then repeatedly bring the hands in closer until passing through presents a moderate stretch of the shoulders. This is your training grip.

Step 3

Be able to perform the pass-through at the top, the bottom and everywhere in between while descending into the squat. Practice by stopping at several points on the path to the bottom, hold, and gently, slowly, swing the dowel from front to back, again with locked arms. At the bottom of each squat slowly bring the dowel back and forth, moving from front to back.

Step 4

Learn to find the frontal plane with the dowel from every position in the squat. Practice this with your eyes closed. You want to develop a keen sense of where the frontal plane is located. This is the same drill as step 3, but this time you are bringing the dowel to a stop in the frontal plane and holding briefly with each pass-through. Have a training partner check to see if at each stop the dowel is in the frontal plane.

Step 5

Start the overhead squat by standing straight and tall with the dowel held as high as possible in the frontal plane. You want to start with the dowel directly overhead, not behind you, or, worse yet, even a little bit in front.

Step 6

Very slowly lower to the bottom of the squat, keeping the dowel in the frontal plane the entire time. Have a training partner watch from your side to make sure that the dowel does not move forward or backward as you squat to bottom. Moving slightly behind the frontal plane is O.K., but forward is dead wrong. If you cannot keep the dowel from coming forward your grip may be too narrow. The dowel will not stay in the frontal plane automatically; you’ll have to pull it back very deliberately as you descend.

Step 7

Practice the overhead squat regularly and increase load in tiny increments. We can put a 2.5-pound plate on the dowel, then a 5, then a 5 and a 2.5, and then a 10. Next use a 15-pound training bar, but only while maintaining perfect form. There’s no benefit to adding weight if the dowel, and later the bar, cannot be kept in the frontal plane.

With practice, you will be able to bring your hands closer together and still keep the bar in the frontal plane. Ultimately you can develop enough control and flexibility to descend to a rock-bottom squat with your feet together and hands together without the dowel coming forward. Practicing for this is a superb warm-up and cool-down drill and stretch.

The overhead squat develops core control by punishing any forward wobble of the load with an enormous and instant increase in the moment about the hip and back. When the bar is held perfectly overhead and still, which is nearly impossible, the overhead squat does not present greater load on the hip or back, but moving too fast, along the wrong line of action, or wiggling can bring even the lightest loads down like a house of cards. You’ve two, and only two, safe options for bailing out—dumping the load forward and stepping or falling backward or dumping backward and stepping or falling forward. Both are safe and easy. Lateral escapes are not an option.

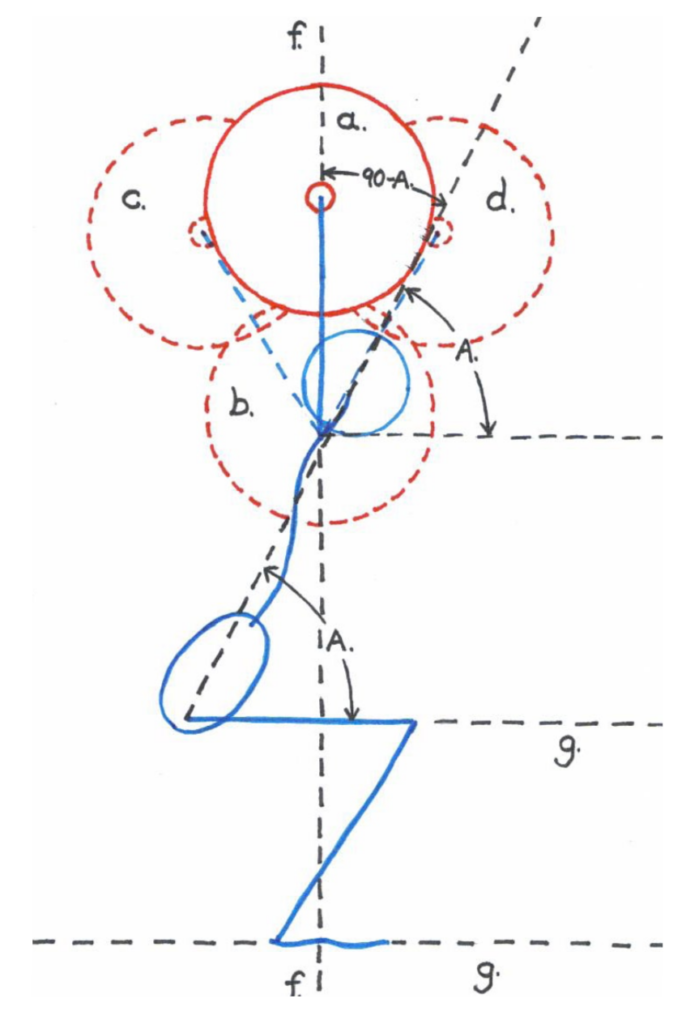

A: The torso’s angle of inclination above horizontal. As a squat matures this angle increases. The squat becomes more upright as the athlete’s strength and neural “connectedness” to the posterior chain increase. Lower angles of inclination are created in an attempt to cantilever away from a weak posterior chain and onto the quadriceps. While technically correct, the lower angle is mechanically disadvantaged.

90-A: This is the angle of rotation of the arms, at the shoulders, past overhead. The lower A is, the greater the rotation, 90-A, required of the shoulders to keep the bar in the frontal plane. The larger 90-A is, the wider the grip required to allow the shoulders to rotate to keep the bar in the frontal plane. Ultimately the connectedness/strength of the posterior chain will determine the width of the grip, elevation of the squat and degree of rotation of the shoulders. Maturity and quality of the squat is a determinant of all of the mechanics of the overhead squat.

g: These lines mark horizontal.

f: This line defines the frontal plane. It divides the athlete’s front half from back half. In the squat (as with most weightlifting movements) the athlete endeavors to keep the load in this plane. If a load deviates substantially from this plane the athlete has to bring the load back, which in turn pulls the athlete off balance.

b: This is roughly the position for a back or front squat.

a: This is the position for the overhead squat. With perfect stability, movement and alignment this position does not increase the moment about the hip or back. The difference in an athlete’s strength when squatting here, overhead, as opposed to position b, the back or front squat, is a perfect measure of instability in the torso, legs or shoulders, and improper line of action in the shoulders, hips or legs, and weak or flawed posture in the squat.

c: This position has the load behind the frontal plane. It can actually decrease the moment on the hip and back. As long as balance is maintained the position is strong.

d: This is a fatal flaw in the overhead squat. Even slight movement in this direction greatly increases the moment in the hip and back. Moving in this direction with even a small load can collapse the squat like a house of cards.

The difference between your overhead squat and your back or front squat is a solid measure of your midline stability and control and the precision of your squatting posture and line of action. Improving and developing your overhead squat will fix faults not visible in the back and front squat.

As your max overhead, back and front squat each rise, their relative measure reveals much about your developing potential for athletic movement.

An average of your max back and front squat is an excellent measure of your core, hip and leg strength. Your max overhead squat is an excellent measure of your core stability and control and ultimately your ability to generate effective and efficient athletic power.

Your max overhead squat will always be a fraction of the average of your max back and front squat but, ideally, with time, they should converge rather than diverge.

Should they diverge, you are developing hip and core strength, but your capacity to efficiently apply power distally is reduced. In athletic pursuits you may be prone to injury. Should they converge, you are developing useful strength and power that can be successfully applied to athletic movements.

The functional application or utility of the overhead squat may not be readily apparent, but there are many real-world occurrences where objects high enough to get under are too heavy or not free enough to be jerked or pressed overhead yet can be elevated by first lowering your hips until your arms can be locked and then squatting upwards.

Once developed, the overhead squat is a thing of beauty—a masterpiece of expression in control, stability, balance, efficient power and utility. Get on it.

This article, by BSI’s co-founder, was originally published in The CrossFit Journal. While Greg Glassman no longer owns CrossFit Inc., his writings and ideas revolutionized the world of fitness, and are reproduced here.

Coach Glassman named his training methodology ‘CrossFit,’ which became a trademarked term owned by CrossFit Inc. In order to preserve his writings in their original form, references to ‘CrossFit’ remain in this article.

- Download Original PDF

- Download Español (Spanish) PDF

- Download Português (Portuguese) PDF

- Download Italiano (Italian) PDF

- Download Français (French) PDF

Greg Glassman founded CrossFit, a fitness revolution. Under Glassman’s leadership there were around 4 million CrossFitters, 300,000 CrossFit coaches and 15,000 physical locations, known as affiliates, where his prescribed methodology: constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity, were practiced daily. CrossFit became known as the solution to the world’s greatest problem, chronic illness.

In 2002, he became the first person in exercise physiology to apply a scientific definition to the word fitness. As the son of an aerospace engineer, Glassman learned the principles of science at a young age. Through observations, experimentation, testing, and retesting, Glassman created a program that brought unprecedented results to his clients. He shared his methodology with the world through The CrossFit Journal and in-person seminars. Harvard Business School proclaimed that CrossFit was the world’s fastest growing business.

The business, which challenged conventional business models and financially upset the health and wellness industry, brought plenty of negative attention to Glassman and CrossFit. The company’s low carbohydrate nutrition prescription threatened the sugar industry and led to a series of lawsuits after a peer-reviewed journal falsified data claiming Glassman’s methodology caused injuries. A federal judge called it the biggest case of scientific misconduct and fraud she’d seen in all her years on the bench. After this experience Glassman developed a deep interest in the corruption of modern science for private interests. He launched CrossFit Health which mobilized 20,000 doctors who knew from their experiences with CrossFit that Glassman’s methodology prevented and cured chronic diseases. Glassman networked the doctors, exposed them to researchers in a variety of fields and encouraged them to work together and further support efforts to expose the problems in medicine and work together on preventative measures.

In 2020, Greg sold CrossFit and focused his attention on the broader issues in modern science. He’d learned from his experience in fitness that areas of study without definitions, without ways of measuring and replicating results are ripe for corruption and manipulation.

The Broken Science Initiative, aims to expose and equip anyone interested with the tools to protect themself from the ills of modern medicine and broken science at-large.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Journal Club: February 5, 2026

When number-chasing replaces treating the root cause

The iceberg beneath “normal” blood sugar numbers