By Malcolm Kendrick

Medicine has always been a highly conservative profession. It is both rigidly hierarchical and highly resistant to change. In large part because those at the top are perfectly happy with the status quo. People at the top usually are. It was the status quo they rode to the top of the profession.

“When I entered medicine, I did not realize that there was such intense pressure to conform. But we learn early on that there is a decorum to medicine, a politeness. A hidden curriculum teaches us not to disturb the status quo, not to question it. We depend on powerful individuals and organizations and are taught that success does not often come to those who ask uncomfortable questions or suggest new ways of providing cae.

“The sense of danger that we feel when we question authority is not unfounded. Those who ask difficult questions or challenge conventional wisdom are often isolated. They may find few opportunities to speak and their writings may not be welcomed. Compliance with normative behavior may be forced by fear of recrimination…”

—Harlan M. Krumhlolz MD SM [1].

William Harvey, circulation of the blood

When it comes to William Harvey, and blood circulation, there were additional powerful forces at work to ensure that new ideas would be ruthlessly stamped on. In this case, the powerful force was the Roman Catholic church. The ultimate authority.

The church was not entirely keen on anyone dissecting dead bodies to find out what was inside, and how they worked. For this was to pry into God’s work, the great mystery of humankind.

In addition, the catholic hierarchy had thrown themselves behind the medical theories of Galen. An enormously influential second century Roman physician. He was considered such an authority on all things medical, that his writings remained pretty much unquestioned for the next fifteen hundred years.

In addition, the catholic hierarchy had thrown themselves behind the medical theories of Galen. An enormously influential second century Roman physician. He was considered such an authority on all things medical, that his writings remained pretty much unquestioned for the next fifteen hundred years.

Indeed, if you dared to contradict Galen, the Spanish Inquisition was likely to pay you an unwelcome visit, and have you burnt at the stake. They were the ultimate ‘fact-checkers’ of their time.

“In 1553, a Spanish doctor and theologian, Michael Servedo (Servetus) published ‘Christianismi Restitutio’, which went against Galen’s ideas, which had the support of the Catholic Church… Servedo was burned at the stake for heresy.” [2]

Burning unbelievers at the stake does have a tendency to hinder scientific research. But what were Galen’s ideas about blood circulation? Ready yourself for some of the most astonishing gibberish.

“According to the Galenic system, blood is created in the liver from ingested food and flows to the right side of the heart. Some of it flows to the lungs where it gives off ‘sooty vapors’ and some flows through invisible pores into the left side of the heart, where it gains ‘vital spirits’ when mixed with pneuma brought in by the trachea. Several arteries flow into a fictional rete mirabile at the base of the brain, where vital spirits are changed to animal spirits before being distributed to the rest of the body through hollow tubes called nerves, where the blood is consumed by the tissues.” [3]

For fifteen hundred years, this is what doctors were taught about how the blood flowed through the body – I was going to write ‘circulate’, but they did not believe it circulated at all. Instead, they thought it was manufactured in the liver, then flowed to the heart. It passed straight through the heart from right to left using ‘invisible pores’. At which point it arrived at various organs and tissues, traveling along the nerves.

At the end of its journey it was consumed by the organs and tissues. At some point in this process it was animated by animal spirits in the brain. The function of the lungs was to give off sooty vapors. Really? Take me through this again, slowly, step by step … Hold on while I pour myself a large whisky and sit back.

It is clear there were many people before William Harvey who thought that Galen’s ideas about blood circulation were utter bunk, including Leonardo de Vinci who wrote obliquely on the matter. Other skeptics probably included every single butcher who ever lived. However, in addition to the ‘burning at the stake’ issue, there was a whole area of medical practice that relied on Galen’s ideas.

These were purging and bleeding. The two biggest money makers for doctors at the time. If it were to become accepted that the blood actually circulated around the body, these two treatments would make even less sense than they already did. At which point we run into another constant, and major barrier to the uptake of new ideas. Money.

As stated by Upton Sinclair, “It is very difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on him not understanding it.”

Medical historians always like to give the impression that the moment someone pushes medical science forward with a new idea, they are lifted shoulder high in front of cheering crowds. They will be garlanded with honors, colleagues kneeling before them in awe at their brilliance. The reason for this, I believe, is to encourage the idea that medicine is always learning, moving forward, supporting innovation. Open minded, flexible…

William Harvey certainly pushed science forward. He demonstrated, beyond any reasonable doubt, how the circulatory system works. Blood flows into the right side of the heart, then it passes through the lungs before arriving back at the left side of the heart. It is then pumped round the body before flowing back to the right side once more.

Was he garlanded by his colleagues…?

In 1628, Harvey published his De Moto Cordis,

“…since this only book does affirm the blood to pass forth and back through unwonted tracts,” wrote Harvey at the time, “contrary to the received way, through so many ages of years, and evidenced by innumerable, and those famous and learned men, I was greatly afraid to let this little book … either to come abroad or across the sea, lest it might seem an action too full of arrogancy…

“Harvey was right to be concerned; his medical practice suffered greatly from all the criticism he received. A whole practice of medicine involving purging and bleeding rested on Galen’s system, and it would not pass away for generations to come. In later life, Harvey became something of a recluse. ‘Much better is it oftentimes to grow wise at home and in private,’ said Harvey,’ than by publishing what you have amassed with infinite labor, to stir up tempests that may rob you of peace and quiet for the rest of your days.'”

Harvey made the terrible, unforgivable error of being right, and threatening the income of his peers. For which act he received a lifetime of criticism and punishment, as his reward. As did Semmelweis – the man who first proposed antiseptic hand washing techniques to prevent infection. He ended up beaten to death in a mental asylum.

Nowadays, the Spanish Inquisition has gone. But you can still be metaphorically burned at the stake by the ‘authorities’.

Why did Galen think what he thought?

Changing direction slightly at this point, I think it is interesting to try and establish how and why wrong ideas come into existence in the first place. Specifically in medical thinking. Are there patterns of thought that we can discern? If so, does this make it easier to change them? Possibly not, but it’s worth a try.

I think the story of Galen highlights one form of thought that I like to call the ‘If you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist’ problem. Only that which we can see, or measure, is important. This is a repeating theme in medical thinking. To give another quick example. The idea that organisms too small to be seen by the naked eye cause infectious diseases. This was pretty much dismissed out of hand.

I think the story of Galen highlights one form of thought that I like to call the ‘If you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist’ problem.

Instead, infections were believed to be spread by Miasma, a nasty smell. It was only when microscopes came into existence, and bacteria could be seen, that medical thinking suddenly changed. ‘Oh, look.’ Maybe John Snow was right after all.

Galen must have known that the heart was a pump of some kind, with chambers and valves. But if you trace the blood vessels out from the left side of the heart they become smaller and smaller until they simply disappear. They certainly cannot be seen by the naked eye. How can blood possibly flow through non-existent channels?

Given that there was no way – at least none that he could see – for the blood to flow through organs and tissues, Galen decreed that when the blood arrived at the tissues it was used up. Gone, in a puff of smoke… and for my next magic trick.

Would you or I have thought the same thing? Or would we have paused for a moment. Hold on, there must be very small blood vessels in there somewhere. After all, the heart pumps about a gallon a minute. No way can the liver possibly be manufacturing that amount. Nor can the tissues be using up that much. That is just not going to happen.

Several of Harvey’s experiments to disprove Galen’s idea were quite simple. They involved cutting open an artery in an animal to see how long it took for the blood supply to run out. Not long, as it turns out. As all butchers of the time knew.

Another problem with Galen’s model, that you might already have spotted, is that for it to work, blood had to be able to pass straight through the heart, from the right to the left, through a muscular wall – the septum. For this to be possible it had to travel through invisible pores.

So, Galen managed to convince himself that there were tiny invisible pores within the heart. Yet there could not possibly be invisible pores throughout the rest of the body? This is another feature of medical thinking. A (wrong) idea becomes widely accepted as the truth. In time, more and more contradictions turn up. However, rather than being discarded, the idea twists and turns, and grows and distorts, in order to keep it alive.

This can, perhaps, be most clearly seen with the cholesterol hypothesis. It began life as ‘high cholesterol causes heart disease.’. When populations were found that had high cholesterol levels and low rates of heart disease the hypothesis was not discarded. For, by this time it had become an established medical fact.

Instead, it transformed into the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ cholesterol hypothesis. Then, the total cholesterol/HDL ratio… hypothesis. The small and dense LDL hypothesis, the non-HDL hypothesis, The small dense, light fluffy LDL hypothesis, the cholesterol particle number hypothesis, the oxidized cholesterol hypothesis the…take your pick, there are hundreds of them nowadays.

Each one represents an attempt to explain a contraindication to the new, adapted, hypothesis. I have to say that I have found it difficult to stamp on something that simply will not keep still. It just changes shape and moves somewhere else at high speed, whilst still managing to remain as the same hypothesis… in some way. Sigh.

Returning to the ‘if you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist’ problem, let us travel forward in time from Harvey, four hundred years, or so.

Here we arrive at the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG). At this point we find ourselves in a world where vast sums of money were being made by cardiovascular surgeons carrying out this procedure. Many were raking in millions each year. See under ‘bleeding and purging’. This is what Bernard Lown had to say on the matter of CABGs.

“Forty years ago I stopped referring most patients with stable coronary heart disease (CHD) for cardiac angiography.) This procedure permits visualizing the extent of obstructed coronary arteries. What occasioned my deviation? The problem was that nearly all those undergoing angiography ended up having surgery, namely, coronary artery bypass grafting, or CABG (pronounced ‘cabbage’).

“What could be wrong with improving blood flow to the heart by unblocking an obstructed or narrowed artery? Such a seemingly commonsense approach would have had the approval of every plumber who encounters a blocked faucet.

“But, first of all, the heart is not a plumbing fixture. When a coronary vessel is narrowed or blocked, the heart has a built-in defense mechanism: It develops a collateral network of small vessels to compensate for the diminished delivery of nutrients and oxygen.“ [4]

I urge you to read this essay. It is by one of the absolute greats of medicine, and a hero of mine.

The main point I wanted to highlight here is not just the money being made from CABGs – which always represents a formidable barrier to progress. The more important barrier was that doctors found themselves transfixed by the large arteries that supply blood to the heart. If they were narrowed, this was obviously a disaster, as blood flow to the heart muscle was seriously impeded, and a heart attack was imminent. The artery must be bypassed immediately using a bypass graft.

What they seemed blissfully unaware of is there is a way for the blood to reach the heart muscle, even if the large artery was narrowed. Which is through invisible ‘pores’ – something called collateral circulation. Collateral circulations allow blood to flow through minute blood vessels that are too small for the human eye to see. Even if, by the mid twentieth century, they were not technically invisible. Everyone could see that they existed. If, that is, they chose to look.

But cardiologists focussed entirely on what they could see… ‘Big artery, narrowing, bad…must treat.’ Did it work? In an acute blockage, such as occurs in a heart attack. Yes it did… Otherwise…no. Not really, or not at all. Depends on which of the thousands of clinical papers you read. Here is the summary of one article from Stanford Medicine.

“Patients with severe but stable heart disease who are treated with medications and lifestyle advice alone are no more at risk of a heart attack or death than those who undergo invasive surgical procedures, according to a large, federally funded clinical trial led by researchers at the Stanford School of Medicine and New York University’s medical school.” [5]

This study looked at CABG, and stents (small metal tubes inserted into coronary arteries to open them up). They found that for the great majority of people, they simply do not work. As Bernard Lown had established over years previously.

As you can see the ‘if you can’t see it, it doesn’t exist’ fallacy has not gone, and probably never will. It continues to drive many areas of medical thinking, and remains a recurring theme.

Summary

This has been a very short run though of some of the barriers to changing medical practice. Often the first thing that happens is for a flawed idea, often based on very limited observations, to take hold, At which point it can quickly become unquestioned ‘fact’ which will be taught to all doctors.

The rigid hierarchy of medicine then defends such facts with great ferocity. The pressure to conform silences most doctors and researchers.This is all made far worse if the flawed ideas themselves underpin massively profitable medical and surgical procedures. Nothing supports a bad idea more effectively than money.

Can it be changed? Not really from within, I do not think.

References:

- A Note to My Younger Colleagues… Be Brave, Harlan M. Krumholz: Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

- William Harvey: History Learning Site.

- The circulatory system, from Galen to Harvey, Steven A. Edwards, Ph.D: AAAS.

- A Maverick’s Lonely Path in Cardiology (Essay 28), Bernard Lown, MD: Dr. Bernard Lown’s Blog.

- Stents, bypass surgery show no benefit in heart disease mortality rates among stable patients, Tracie White: Stanford Medicine, News Center.

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

One Comment

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio

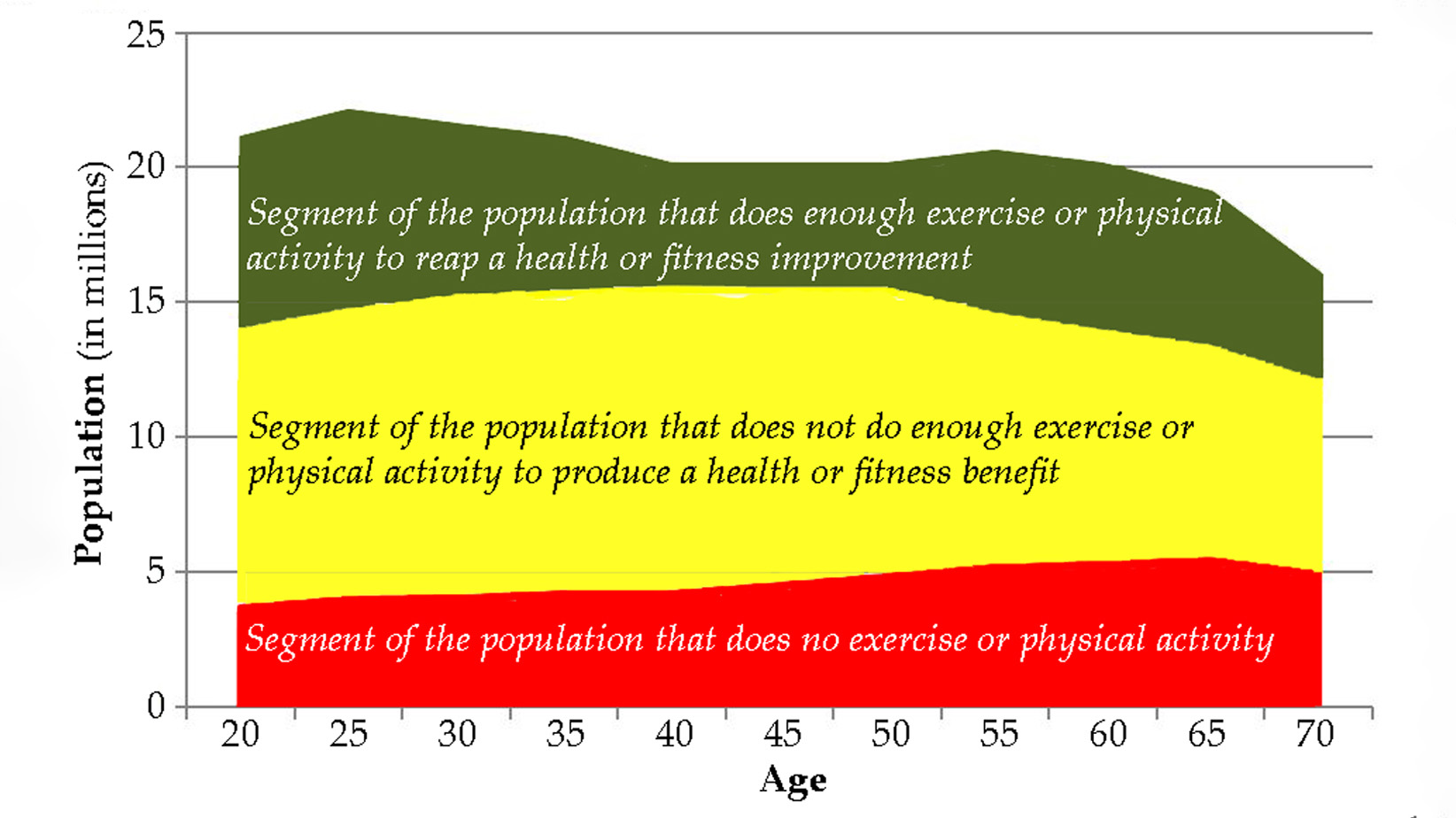

Maintaining quality of life and preventing pain as we age.

Excellent article! I was not aware of William Harvey’s story, but it could have been repackaged with minimal changes and published any time during the pandemic.

You are right about the influence of money on science. It is like a vitamin that enables a hypothesis to evolve and overcome any objection.