By Maryanne Demasi, PhD

The case shines a light on how journalists cover scientific issues and how the media seeks to discredit those who challenge the official narrative.

In the UK, two medical experts have earned a major win in the High Court in a case described by the Judge as “the most significant piece of defamation litigation” he has seen in a very long time.

The case shines a light on how journalists cover scientific issues and how the media seeks to discredit those who challenge official narratives.

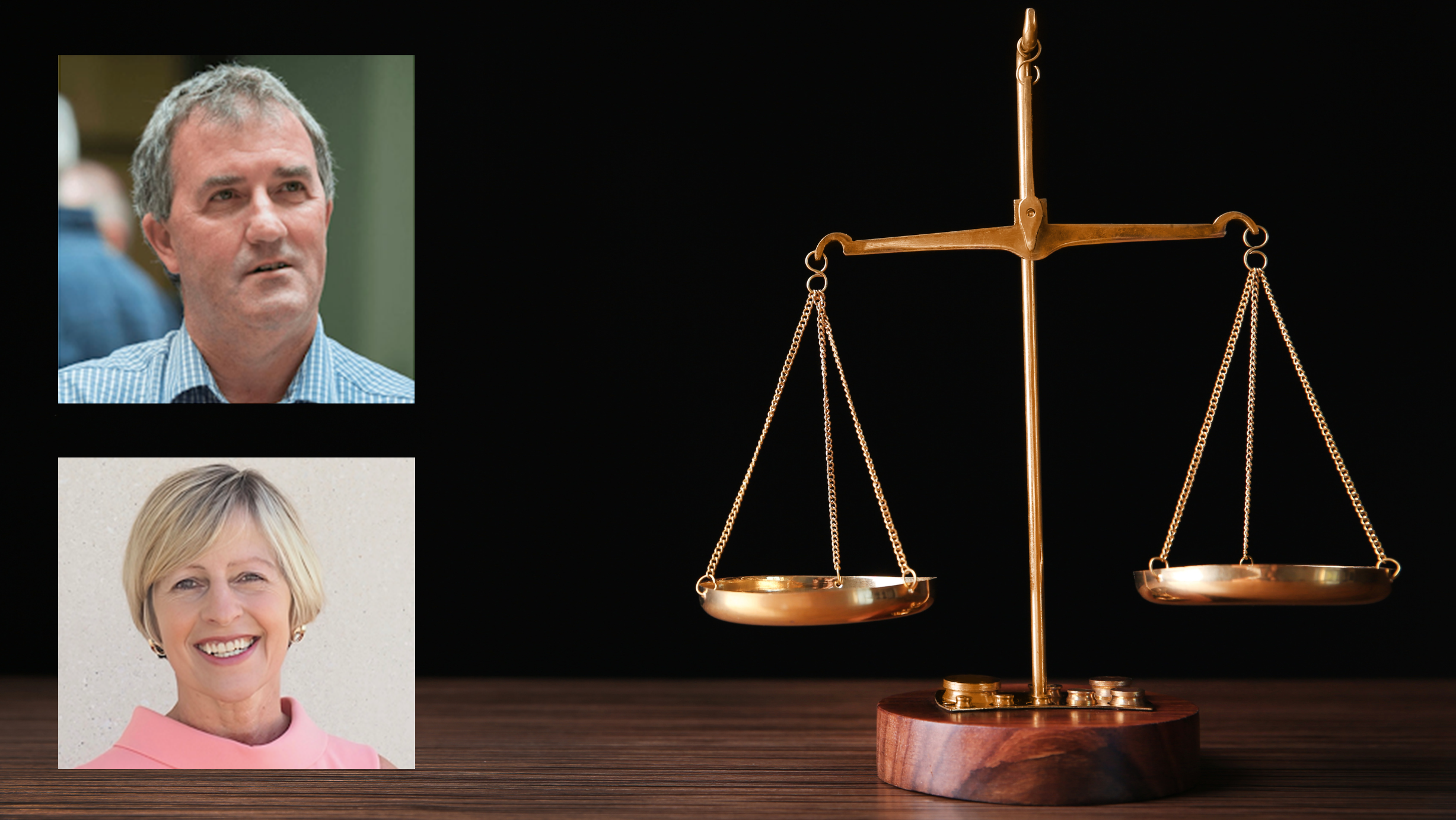

For decades, Malcolm Kendrick, general practitioner and Zoe Harcombe, PhD in nutritional science, have publicly challenged the role of saturated fat and cholesterol in heart disease, as well as the widespread use of statin medications.

Their views are contradicted by ‘medical dogma’ which contends that high intake of saturated fat raises cholesterol and causes heart disease. Some proponents argue that cholesterol-lowering statins are so safe that they could be put in the water supply.

In 2019, journalist Barney Calman began working on a series of articles to promote the benefits of statin drugs, and attack doctors he called “statin deniers.” It was part of the Mail on Sunday’s campaign to ‘Fight Fake Health News’ and counter medical misinformation.

In the articles, Calman branded Kendrick and Harcombe as “pernicious liars” who put millions at risk of debilitating heart attacks and strokes, responsible for a “public health catastrophe” with far graver consequences than the MMR scandal.

Calman went so far as to suggest there was “a special place in hell for the doctors who claim statins don’t work.”

Calman and his publishers, Associated Newspapers Ltd, refused to apologise, remove or alter the offending articles. Kendrick and Harcombe sought legal advice in March 2019, and subsequently sued for libel in February 2020, arguing the articles “caused serious harm” to their reputations.

The counterargument put forward by Calman and Associated Newspapers Ltd was that the articles were simply “honest opinion,” published as a “matter of public interest” and therefore protected under the Defamation Act 2013.

Last month, however, Justice Matthew Nicklin issued a 255-page judgement and dismissed a “public interest defence” because the articles in question had “seriously misled readers.”

The ruling now opens the door for Kendrick and Harcombe to proceed to the next phase of the lawsuit.

Evidence so far

Upon reading the judgment, evidence in the case portrays Calman as a journalist with tunnel vision who “planned a big takedown” of his targets, and who misrepresented the facts in order to fit a predetermined narrative.

Justice Nicklin suggests that Calman allowed himself to be used as a patsy, and to be unduly influenced by well-known professors whose primary interest was to advance their own agenda.

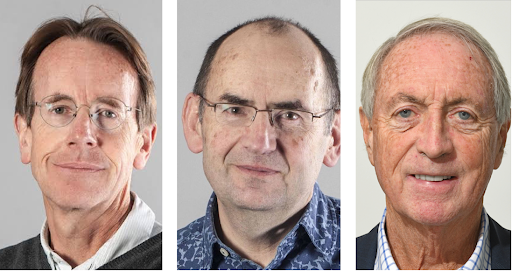

‘The Professors’ included Rory Collins, Peter Sever, and Colin Baigent who co-authored a 2016 review in The Lancet which promoted the wider use of statins, even for people at low risk of heart disease – a view that Kendrick and Harcombe had publicly challenged.

Their advocacy of statins to lower cholesterol is well-known.

Collins told Calman that anyone who thinks LDL-cholesterol does not “cause” heart disease is akin to “flat earthism” and “in the same realm as claiming that smoking does not cause lung cancer.”

The Professors also published a 2019 study in The Lancet claiming that statins prescribed to people over the age of 75 could save thousands of lives. It garnered a lot of media attention after Baigent said that offering statins to everyone over 75, could save 8000 lives a year.

But Baigent and his team came under heavy fire from various experts, including Harcombe who published a rapid response in The BMJ (and newsletter) arguing that such a claim was not supported by the statistical data in the study.

Harcombe’s criticism is what put her in Calman’s crosshairs. Calman sent her criticism to Baigent for a response but never heard back.

In court, Calman admitted during cross-examination that he had no expertise in statistical analysis, nor did he fully understand the detail of Harcombe’s criticism of The Lancet study.

When Justice Nicklin analyzed the evidence, he determined that Harcombe had actually made “a valid point that The Lancet 2019 Study did not support the claim, attributed to Professor Baigent, as to the number of deaths that could be avoided in the over 75s with statin treatment.”

Kendrick found himself on Calman’s list of “statin deniers” after publishing multiple articles and books on why cholesterol is not the cause of heart disease.

For decades, Kendrick (like Harcombe) criticized the official advice that if you reduce saturated fat intake, you can lower your so-called ‘bad’ LDL-cholesterol.

But when Calman asked another doctor to contest the claims, he did not get the response he was expecting. The cardiologist – who wasn’t named in the court documents – wouldn’t contradict Kendrick’s view.

“So, Kendrick is right?” Calman then asked the cardiologist in an email.

“I wouldn’t like to have to defend the argument that high intake of saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol,” replied the cardiologist.

Calman responded, “It doesn’t look good for the medical prof[ession]. If you are giving non evidence based advice. The NHS is giving fake news in this case.”

Calman’s articles did not accuse the NHS of peddling fake news, but he did resort to branding Kendrick and Harcombe as dishonest brokers, who “make money from saying statins don’t work” and focused on the business of selling books that downplay the role of cholesterol in heart disease.

Media misrepresented facts and misled readers

While researching his stories, Calman decided he would seek a comment from Matt Hancock who was the UK’s Health Secretary at the time. Hancock provided a blistering rebuke of people who spread “pernicious lies.”

But Hancock was not referring to any particular individual, he was merely providing a general statement about the dangers of health misinformation.

Kendrick and Harcombe argued that the use of Hancock’s statement about pernicious lies would lead any reasonable reader to believe that it was about them.

Justice Nicklin, in his judgment, stated that neither Hancock nor his office staff knew the statement was going to be used to criticize named individuals, and therefore was “seriously misleading” to readers.

Calman’s lack of journalistic rigour did not end there.

His narrative was that people would stop taking statins after hearing negative stories in the press, and it would lead to unnecessary heart attacks and strokes. However, Calman needed a “case study.”

Calman put out a call for people to come forward and tell their stories, but he was apparently “inundated by stories of people who have stopped taking statins and felt far healthier.”

He also received “two quite dramatic stories” of patients who were taken off their statins by their doctors after they developed serious liver problems and died from complications. “The families themselves both naturally question whether statins caused the problems,” noted Calman.

All these case studies contradicted the narrative that stopping statins was dangerous, so Calman wrote to the Professors. “What we haven’t had is a single story which backs your thesis, and obviously I’m concerned,” he explained. “I think it makes us look rather weak.”

Calman pressed the Professors to find a case study. “Have any of you [had] a real-life example of someone who has suffered a heart attack or stroke because they declined/quit statins because they thought they didn’t really work anyway, or similar?” asked Calman.

A patient by the name of “Colin” eventually came forward, but Calman committed the cardinal sin in journalism – he misrepresented the interview.

Transcripts of the interview revealed that Colin did not stop taking his statins because he’d been influenced by negative stories in the media, but because the medication left him feeling lethargic and he also had digestion problems.

Colin, an avid radio listener, denied that he’d been influenced by misinformation on the radio because he said, “I like to make my own mind up.”

After reading the transcripts of the interview, Justice Nicklin agreed they “provided very little (if any) support for the suggestion that Colin had given up statins because of misinformation he had seen or heard in the media.”

Justice Nicklin wrote, “The quotations, attributed to Colin [in the article] are both inaccurate. Colin did not say this in his interview. At best, these ‘quotations’ represent Mr Calman’s inaccurate synthesis of the interview. They materially misrepresented the totality of what Colin had said.”

The right-of-reply

When it came to giving Kendrick and Harcombe a right-of-reply, Calman only allowed less than 24 hours to respond to a series of complex questions. This contrasted the lengthy correspondence Calman had with the Professors who’d already seen a draft of the article.

To their credit, Kendrick and Harcombe wrote strong rebuttals with credible references, denying the accusations leveled against them. So, Calman revised his article, adding their quotes to provide more balance.

But when Calman sent the revised version to the Professors, they made their objections known.

“Oh dear, what a shame. It is extremely disappointing how the balance of the article has been completely changed at the last minute by the influence of the unbalanced inclusion of quotes from Harcombe and Kendrick,” wrote Professor Collins.

Collins then suggested “a major revision” to bring the article “back to somewhere closer to what it had been.”

Professor Sever was reticent to give Kendrick and Harcombe any leeway. He wrote, “The way the article now reads seems to give credibility to some of their assertions.”

Calman had to insist on including quotes from Kendrick and Harcombe to avoid editorial complaints, but he did redraft the article again, to accommodate the Professors’ demands.

Surrendering editorial control

Allowing the Professors to review the full article before it was published presented an obvious risk that they would seek to exercise a disproportionate influence over the editorial decision-making and final version.

In the judgment, Justice Nicklin wrote that the Professors represented one side of the debate, “there was a clear risk that they had ‘an axe to grind’” and wished “to convey their evidence and arguments, almost to the exclusion of all others.”

It was put to Calman in cross-examination that all the opportunities he gave the Professors to edit his draft articles effectively “surrendered, or fettered, his editorial judgment as a journalist.” But Calman denied it.

Justice Nicklin wrote that Calman inevitably felt pressured to make the edits suggested to him, and that he was being “used” by the Professors to advance their agenda.

“The changes he made shifted the balance of the Article materially to the disadvantage of the Claimants [Kendrick and Harcombe] and, perhaps most importantly, added emphasis to the suggestion that the Claimants’ actions were driven by financial motives,” noted Justice Nicklin.

Overall, Justice Nicklin’s assessment found the totality of the evidence indicated that Calman’s articles were “fundamentally unbalanced, and had been from the outset.”

He said Calman treated Kendrick and Harcombe “as outsiders to the process, and, from the start, had been identified and treated as the ‘targets’ of the articles; to be exposed as proponents of ‘fake health news’ about statins.”

Further, he noted Calman gave full draft articles to the Professors and a “generous period within which to respond.”

In contrast, Kendrick and Harcombe were given no draft article “to enable them fully to understand the range and gravity of allegations they faced. They were, instead, given only a précis of some of the allegations that were to be made against them, and were given less than 24 hours to respond.”

The judge determined that Calman had “written off” the ample evidence given to him from Kendrick and Harcombe in their right-of-replies and did not accept Calman’s claim that it was due to a lack of “space” in the article.

While the Judge accepted that alleged misinformation regarding statins was one of significant interest, Calman acted to “misrepresent important facts relating to the statin debate and to deny readers important details of the material upon which the Claimants had relied in their own defence of serious charges of wrongdoing.”

Justice Nicklin pointed to the “palpable irony” that Kendrick and Harcombe had been accused of being “purveyors of misinformation” when Calman and his publishers had themselves “seriously misinformed their own readers.”

In conclusion, the judgment stated:

“Mr Calman set out to publish a “polemical” “takedown” of the Claimants. He achieved that, but, in my judgment, his belief that publication of the Articles was in the public interest was not reasonable. Therefore, my conclusion is that the public interest defence for the print publication of the Articles fails, and it will be dismissed.”

Following the judgment, Harcombe said she was delighted by the outcome, “I am grateful to the Judge for his detailed and careful analysis of all of the facts and pleased that he has recognised the enormity and unfairness of the public attack on our integrity.”

Kendrick said he was also pleased with the Judge’s ruling, “It was always our position that we had not been treated fairly by the publishers, and the Judgment sets out clearly how badly we were in fact treated.”

Kendrick and Harcombe have indicated they will move to the next phase of the lawsuit in due course.

Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in rheumatology, who writes for online media and top tiered medical journals. For over a decade, she produced TV documentaries for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and has worked as a speechwriter and political advisor for the South Australian Science Minister. She is a 2023 Brownstone fellow.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life

The brain is built on fat—so why are we afraid to eat it?

Q&A session with MetFix Head of Education Pete Shaw and Academy staff Karl Steadman