You’re in your doctor’s office, looking over your latest bloodwork. Your HbA1c (A1c) comes back at 5.7, and the doctor smiles—“You’re fine for now, but let’s keep an eye on it.” Still, something about it sticks with you. What does that number actually mean? What if it’s not fine at all—what if it’s just the tip of something bigger?

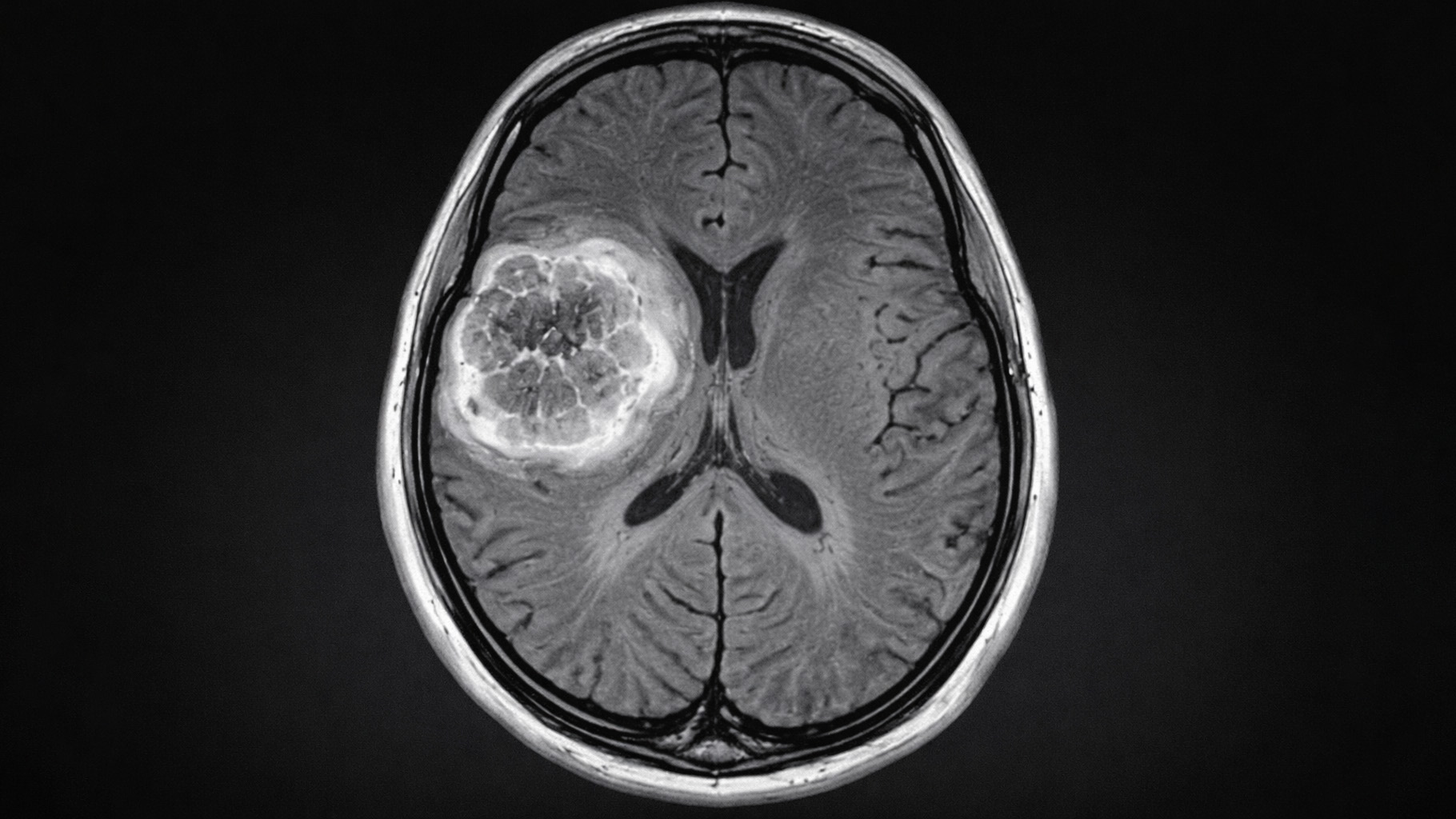

The surface may look calm, but below it, an iceberg of metabolic damage is quietly taking shape. Your A1c result is just the visible tip of that iceberg—a snapshot of sugar in the bloodstream. Beneath the surface lies the older ice of glycation—neurons, vascular walls, and structural proteins slowly accumulating damage over time. As the iceberg sinks deeper, it traps rocks, sediment, and pockets of ancient gas—just as glycation traps waste products, inflammation, and oxidative stress in slow-turnover tissues. What we see in the blood reflects the last few months of sugar exposure—it’s relatively recent and reversible. What lies below represents years of slow, cumulative injury in deeper tissues—older damage that’s far harder to move.

Glycation happens when sugar binds to proteins, lipids, or DNA—warping their shape and function, often permanently. Once a molecule is glycated, there’s no undoing it. The only fix comes through turnover: breaking down damaged cells and rebuilding new ones. Fast-renewing tissues like skin and liver can recover quickly, while slow-turnover systems—cartilage, nerve tissue, vascular endothelium—carry that burden for years. Less sugar means slower glycation, giving your body’s renewal cycles a chance to keep pace. That’s the essence of glycation: chemistry that quietly determines your future resilience or your decline.

A1c is the fingerprint of that chemistry. It’s the share of your red blood cells’ hemoglobin bonded with glucose—a 90-day snapshot of how sugary your blood has been. Clinically, anything below 5.7 % is considered normal. In practice, we often see athletes closer to 5.1–5.3 %, which may reflect better fuel regulation and nutritional tolerance.

A1c captures only what’s visible above the surface.. It shows what’s happening in your blood, but not what’s occurred in your brain, joints, or nerves. Beneath the surface, glycation from glucose and fructose is already corroding performance, recovery, and long-term health.

Each blood sugar spike—every processed carb or sweet treat—adds another microscopic layer of glycation your body has to repair. These reactions occur both in the bloodstream and along vessel walls and connective tissue, where glycation creates crosslinks that stiffen and weaken those structures over time. This process contributes to the vascular stiffness and metabolic wear that mark early chronic disease.

That’s what your A1c captures—a 90-day record of sugar exposure, reflecting the average lifespan of a red blood cell. It tells the story of how consistently your blood has carried glucose, rather than moment-to-moment spikes. But it only shows part of the chemistry. Glucose bonds directly to hemoglobin, forming measurable glycated blood (A1c), while fructose reacts even faster with proteins in other tissues—muscles, joints, and neurons—where the damage can’t be easily tracked. Both sugars drive the same end result: advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that stiffen tissues, inflame vessels, and slow recovery.

At 5.7, medicine calls it prediabetes. At 6.4, diabetes. But glycation begins long before those lines get drawn. By the time A1c hits 6.0, the chemistry is already cooking—and that test still says nothing about fructose damage. High-fructose foods—soda, juice, sauces—elevate methylglyoxal, a highly reactive byproduct of sugar metabolism that rapidly binds to proteins and fats, forming crosslinks in slow-turnover tissues like collagen and neurons. Fructose acts less like food and more like a chronic toxin, elevating uric acid (a known driver of gout), compounding mitochondrial stress and fat storage, adding yet another layer beneath the iceberg. That’s damage you won’t catch in a lab—but you’ll feel it in your joints, your sleep, and your recovery.

Early metabolic decline shows up before the lab results—as soreness that lingers, recovery that stalls, and output that fades early. The solution isn’t always tweaks in the workouts; it’s adjustments in the nutrition. Just as we teach the neutral spine for movement integrity, we also teach A1c for metabolic integrity. A coach who understands glycation can see what medicine misses: performance loss as the earliest biomarker of chronic disease.

In medicine, A1c helps diagnose diabetes. For us, it’s an early warning of a looming disaster. When A1c rises, the iceberg is growing—and the danger is rising with it. Glycation is already hardening what lies below the surface, long before symptoms appear.

The iceberg isn’t inevitable—it builds with poor choices. But it can melt with better ones. For trainers, that’s the opportunity: to see A1c not as a lab number but as a coaching metric—a signal of how well the athlete’s metabolism is responding to nutritional inputs. The sooner we act, the smaller the iceberg gets.

Health outcomes aren’t random. They’re dependent on two variables: what you ate and how you trained. The path out is straightforward: Little fruit. No sugar. Off the carbs, off the couch—Less glycation. A coach who understands this can intervene sooner and restore capacity before medicine even gets involved.

Hollis Molloy is a career coach and Certified CrossFit Level 4 Trainer who served on the CrossFit HQ Seminar Staff from 2007 to 2025 and has owned CrossFit Santa Cruz since 2008. He continues his work as CrossFit Santa Cruz while expanding into MetFix Santa Cruz and serves as a member of the MetFix Academy Staff, teaching and developing education for coaches on metabolic health and performance.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

4 Comments

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

How a Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Naturally Activates the Same Pathways

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life

A great article, thank you Hollis!

Great article, really like the metaphors utilised to aid with understanding. Going to have my members read this.

This article is meant to scare you a bit, on purpose, but there is hope. If your A1C is high, you are not broken. You are getting feedback, and the best part about feedback is that you can respond to it. You do not have to throw out your training or your identity as an athlete. You just get to tighten the plan so your health matches your effort.

Your body will start rewarding you sooner than you think. Some things turn over fast. Your gut lining refreshes in about 3 to 5 days, and shorter-term glucose markers can reflect progress in 2 to 3 weeks. Skin is more like 40 to 56 days. A1C is the longer report card, about 8 to 12 weeks, so do not panic if week two does not look dramatic yet. Stay steady. The long-game tissues take years, which is exactly why consistency wins. Small changes, repeated, are how you become the athlete who is not just fit, but durable.

Great explanation!