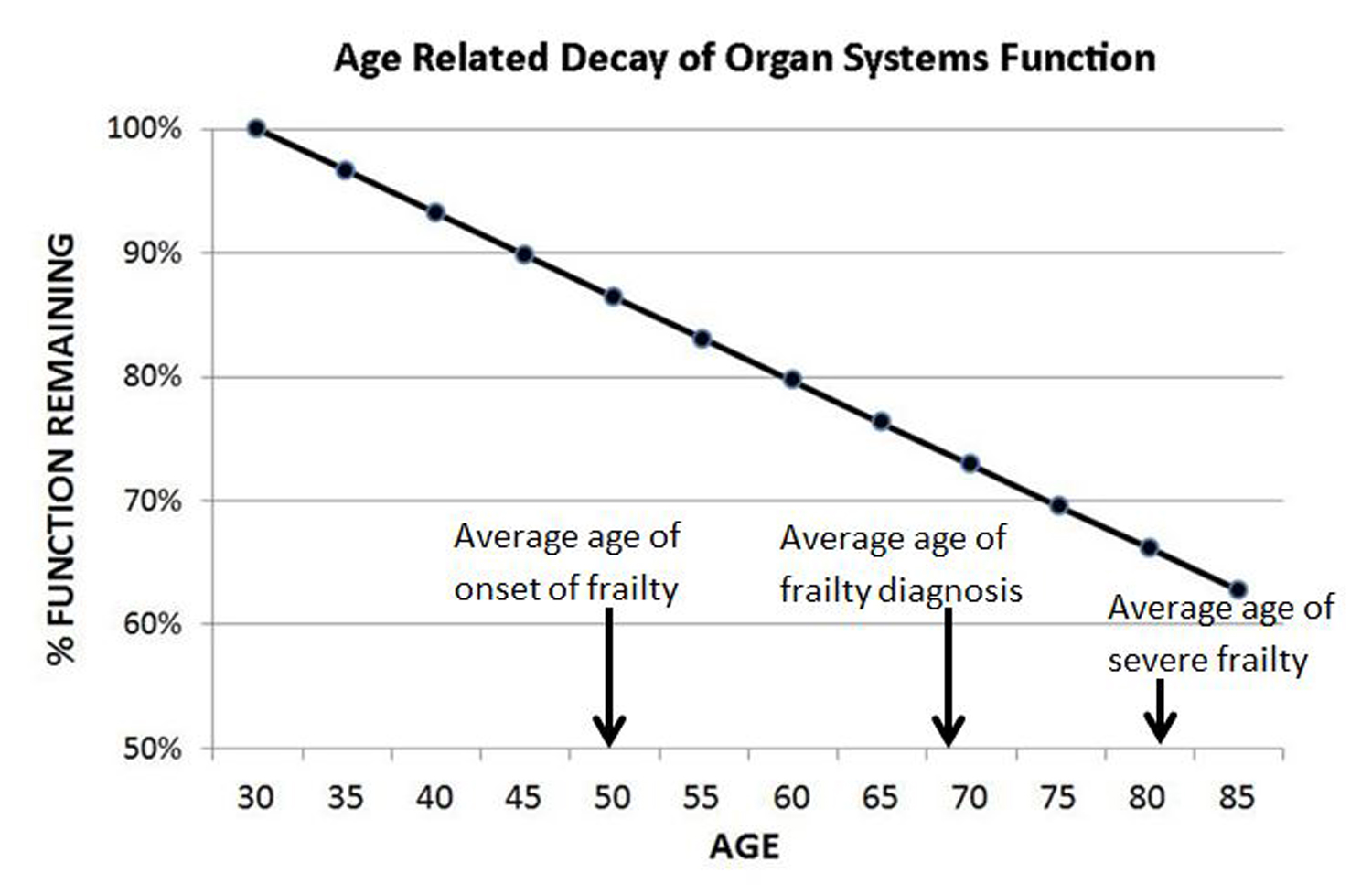

Much has been written in the popular press regarding the inevitable loss of physical function in one’s later years of life. Most of those articles do not provide any concrete data in support of that notion; they simply parrot a conjecture from non-replicated scientific research. Specifically it has been long proposed that about some small percentage of each organ system’s ability to carry out its biological processes is lost each decade after 30 years of age. If we seek out published experimental data on the subject and plot out that concept into graphic form we see that there appears to be a naturally occurring loss of overt function (senescence) over the adult lifespan:

Figure 1. With each passing year after age 30, the biological systems of the body begin to become less efficient in their function. Each year it is conjectured that we lose about 0.68% (less than 1%) in functional capacity compared to our 30 year old self. These losses while small, and virtually imperceptible in late middle ages, are dangerous as they accumulate in a devastating fashion in older age groups. (Organ decay data derived from Sehl et al, Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56(5): 8198-8208, 2001; Age and frailty data from Walsh et al, Age and Ageing 52: 1-9, 2023)

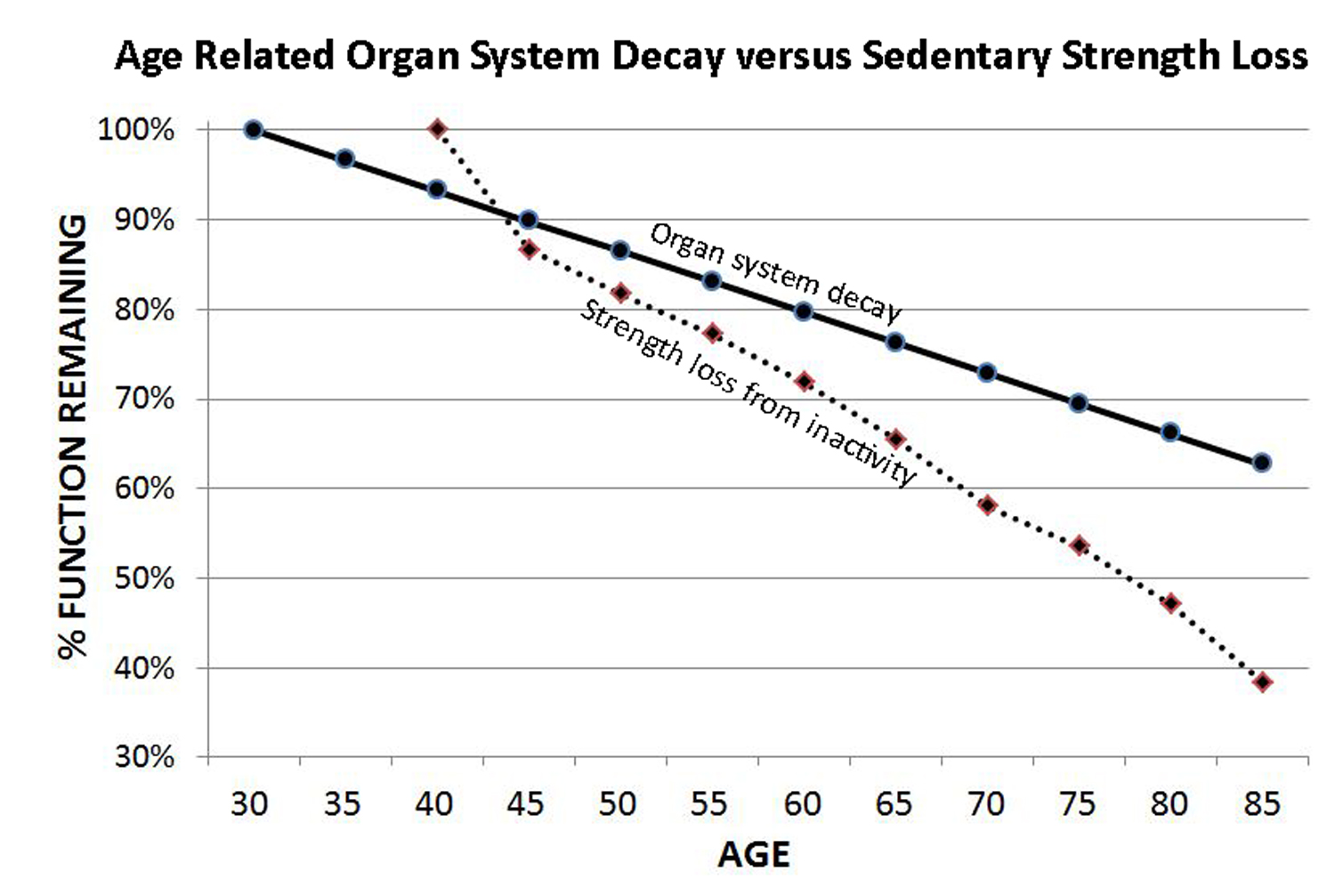

If we accept this data as representing the reality of a sedentary life and we focus our attention on the basic anatomical and biological systems that carry out bodily movement, we see that there is some support for this conjecture in respect to strength over the lifespan:

| System | Yearly Rate of Decay |

|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | 0.36% |

| Neural | 0.77% |

| Circulatory | 0.44% |

| Respiratory | 0.84% |

| Thermoregulatory | 0.95% |

If exercise-supporting physiological systems are functionally eroded with age, does the conjectured rate for those organ system’s functional losses parallel the loss of strength seen in sedentary, non-exercising, populations?

Figure 2. Strength loss in sedentary populations occurs at a faster rate than organ function decay, indicating more than simple erosion of anatomical and physiological systems affects fitness loss.

While organ system functional loss and strength loss over the lifespan are strongly correlated (causation is not inferred), the rate of strength loss does not parallel organ system functional decline. Strength is lost faster than organ function. This relationship is interesting as the musculoskeletal system has the slowest rate of decay of all systems (0.36% loss per year after 30). So, when we consider that the above data is from non-exercising populations, it begs the question; can exercise of any kind slow, or even eliminate, the loss of anatomical and physiological status considered to be the inevitable result of getting older?

Evidence of Human Potential: Sporting Records

If physiological decay from simply getting older diminishes the function of the systems that produce movement and support exercise, then it follows that actual physical performance of exercise will similarly decay over the lifespan.

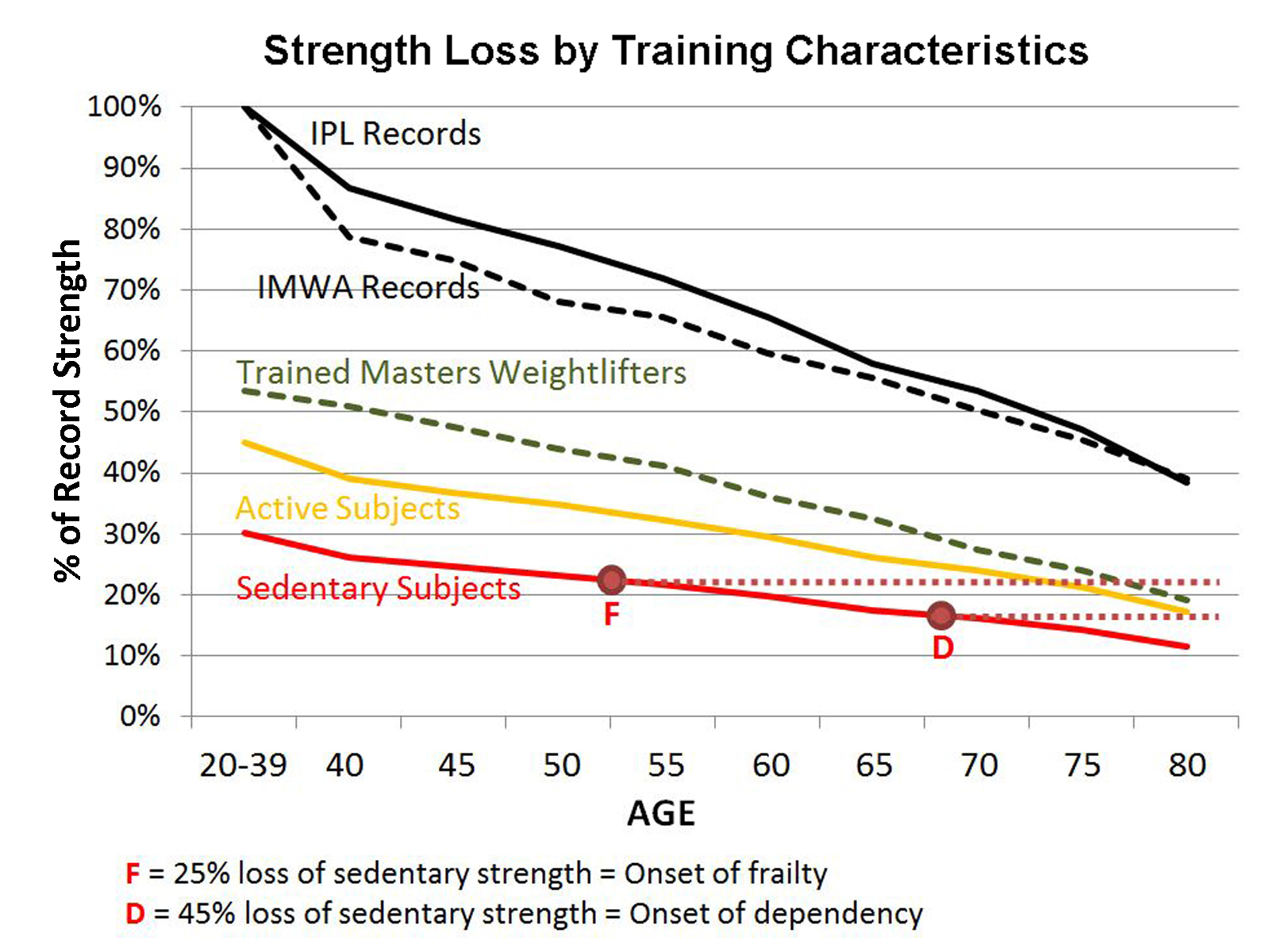

National and world records in sports that have lifespan participation programs (“Masters” competitions) can be informative here. Athletic records from two sports organizations conducting competitions for older populations, or “masters athletes”, can help us plot out the decay in strength that occurs even with continued training. International Masters Weightlifting Association (IMWA – formerly IWF Masters) records and International Powerlifting League (IPL) records provide us with two related but differing data sets. USAMW contests the Snatch and Clean & Jerk, two very ballistic and gymnastic lifts; high velocity strength. IPL contests the Back Squat, Bench Press, and Deadlift, all three high load and slow lifts; low velocity strength. Using that data we can track the patterns and magnitudes of strength loss over the lifespan.

Figure 3. Competitive performances that set “IPL records” and “IMWA records” indicate the performance potential to which individuals can aspire. As such records represent 100% of potential human strength. The “trained masters weightlifters” line represents the actual recorded competition results of the average competitive weightlifter expressed as a percentage of record performances (derived from 50 years of data on every competing USA master weightlifter). The “active subjects” line represents the strength level of a person who meets the Surgeon’s General guidelines for physical activity (but does not lift). This group’s strength level is a smaller fraction, about 45%, of record holder’s strength levels. The lowest strength level, relative to potential human strength and the other groups, is in “sedentary subjects” who are approximately 30% as strong as record holders of the same age and weight.

Note that each sport, weightlifting and powerlifting (IMWA high velocity strength and IPL low velocity strength) has a similar pattern of performance decay. However, high velocity strength appears to decay much faster before age 40 than low velocity strength. After that low velocity strength decays slightly faster until the two types of strength converge in level of strength loss at about age 80. If we extrapolate the lines of record strength decay out over older ages, we see that record holders may not approach frailty level strength until about age 100 … IF they stay competing at that level. Unfortunately less than a handful of weightlifters continue training and competing after 80.

Sadly, organizational records (sports performance records) do not describe the greater population of the USA. They specifically represent what magnitude of strength performance is possible by a single individual of a specific age and bodyweight who specifically trains for and competes in either of these sports. They do indicate that high levels of strength, compared to sedentary persons, can be achieved at any age; however, there appears to be inevitable age-related strength decay just as the popular press reports. Further, when we look at all male competitors competing in USA masters weightlifting between 1975 and 2024, we see that the slope of the line (green dashed line in figure 3) shows strength decay in that specific population is lower than the records line at any age, but nearly mirrors the rate of strength loss plotted with records data. The line of strength loss within active masters weightlifters exists in between the higher records line and the lower sedentary line of strength loss. This supports the conjecture that regular and long term weight training will result in retention of more physical work capacity with increasing age. The data presented here suggests that training like that of a competitive weightlifter or powerlifter can stave off the onset of frailty by nearly 25 years and the onset of dependency by about 15 years. The closer one gets to record performance, the more unlikely the descent into frailty and dependence becomes.

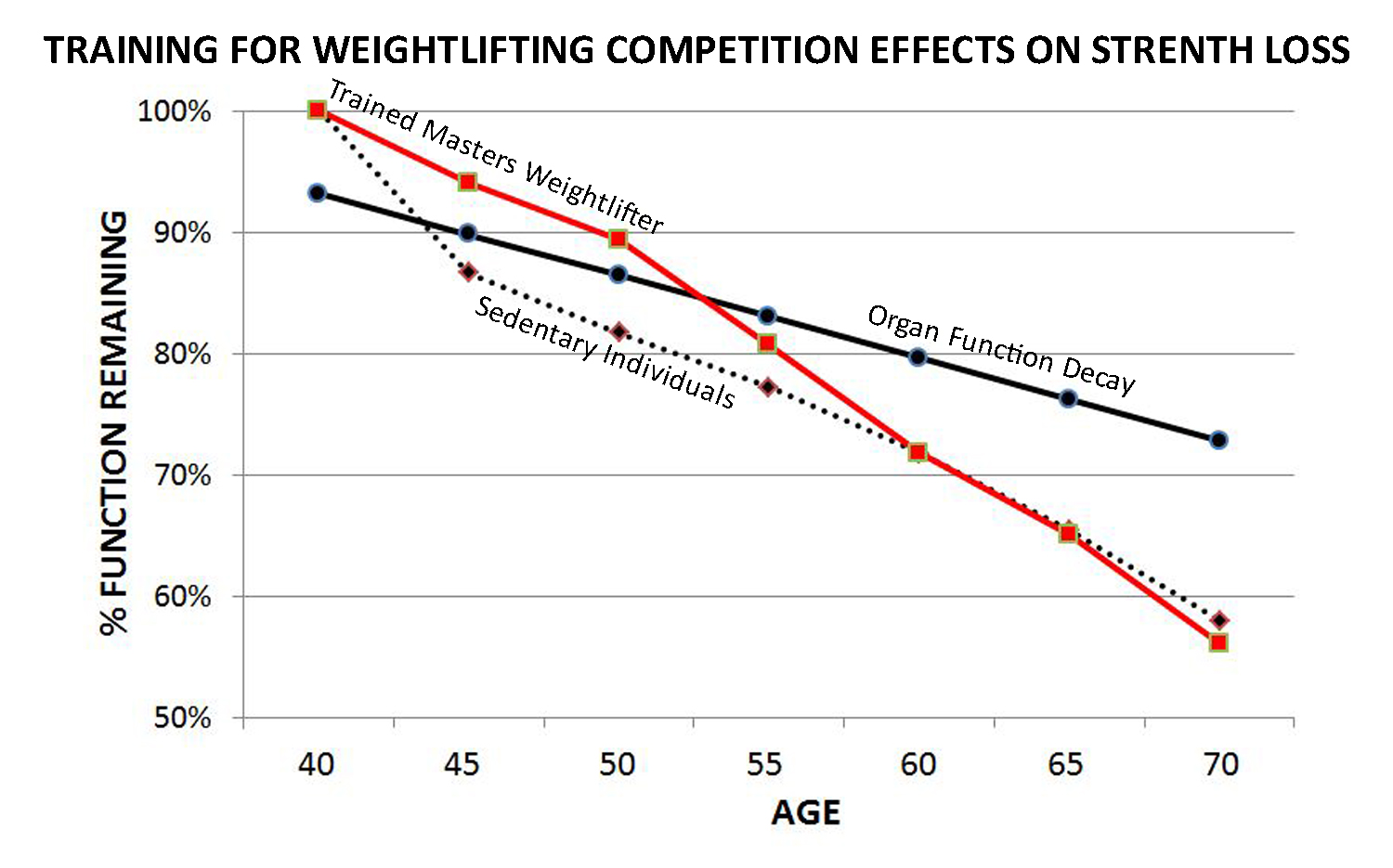

If we compare the rates of decay between conjectured organ systems decay, strength decay in the sedentary, and the rate of performance decline in masters weightlifters, we see that initially training for weightlifting competition seems to slow functional decline to be somewhat similar to the rate of organ system decline. However, between ages 50 to 55 the slope changes and the rate of strength losses amplify to far exceed organ system functional losses.

Figure 4. We expect that training with weights to increase strength, as masters weightlifters do, will keep physical function retained at a higher rate than we would see in sedentary people. While this is true, the rate of strength loss in weightlifters does not parallel the slope of organ function decay or sedentary strength loss.

There are a couple important considerations here: (1) Participation in powerlifting and weightlifting, while relatively popular sports, represents a very small fraction of the overall population and (2) why is there an uncoupling of organ system functional decay rate and strength decay in weightlifters after age 50 to 55?

The first consideration is that at present, sports participation is a very small contributor to physical activity and exercise participation in the USA. The total number of all adult athletes, amateur and professional, in all sports in the USA is actually fairly low:

| Age | Number of Americans in Age Range | Number of Athletes | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 21,000,000 | 1,900,000 | 8.8 |

| 25 | 22,000,000 | 1,400,000 | 6.1 |

| 30 | 21,500,000 | 900,000 | 4.1 |

| 35 | 21,000,000 | 600,000 | 3.0 |

| 40 | 20,000,000 | 600,000 | 3.0 |

| 45 | 20,000,000 | 400,000 | 2.0 |

| 50 | 20,000,000 | 300,000 | 1.4 |

| 55 | 20,500,000 | 200,000 | 1.1 |

| 60 | 20,000,000 | 300,000 | 1.3 |

| 65 | 19,000,000 | 200,000 | 1.3 |

| 70 | 16,000,000 | 200,000 | 1.2 |

| 75 | 11,000,000 | 100,000 | 1.0 |

| 80 | 6,000,000 | 50,000 | 0.8 |

So in respect of the entire USA population, fewer than 3 people per 100 aged 20 to 80 compete as athletes. Those that compete in strength sports likely represent less than 5% of this population. However, as most sports use weight training as a means to improve competition performance, it is likely that their strength decay is similar in pattern. Further, observed strength levels would be lower than weightlifting and powerlifting athletes at all ages; on figure 3 it would be below “trained masters weightlifters” and above “active subjects”.

If we consider only people that meet the US Surgeon’s General Healthy People physical activity recommendations (but do not lift weights) we see that published research data suggests that they start adulthood with about 45% of the strength of record holding athletes of the same age. Interestingly, the slope of strength decay for the physically active is less than that of bodyweight matched record holders and trained masters weightlifters (see figure 3). Further, we also see that those that do not train with weights nor are physically active start adulthood with a strength level of approximately 30% of bodyweight matched record holders. Put into the context of “frailty”, defined as a loss of 25% of sedentary strength, a sedentary lifestyle puts one on a path to enter the early stages of frailty by about age 52. An active lifestyle, one that meets physical activity guidelines, pushes entry into frailty to approximately age 72, a massive benefit. Weightlifting training for competition pushes frailty back a further five years to about 77 years of age at the onset of frailty.

The second consideration – Why does the rate of strength loss in trained masters weightlifters increase after age 50? – is a bit difficult to answer with the limited data available. The most likely explanation for this is not that turning 50 triggers a significant and negative change in anatomical or physiological capacity; rather the root of the issue is more likely that the volume and intensity of training changed. We can see an example of this by simply enumerating the number of training sessions normally included in training plans by age group:

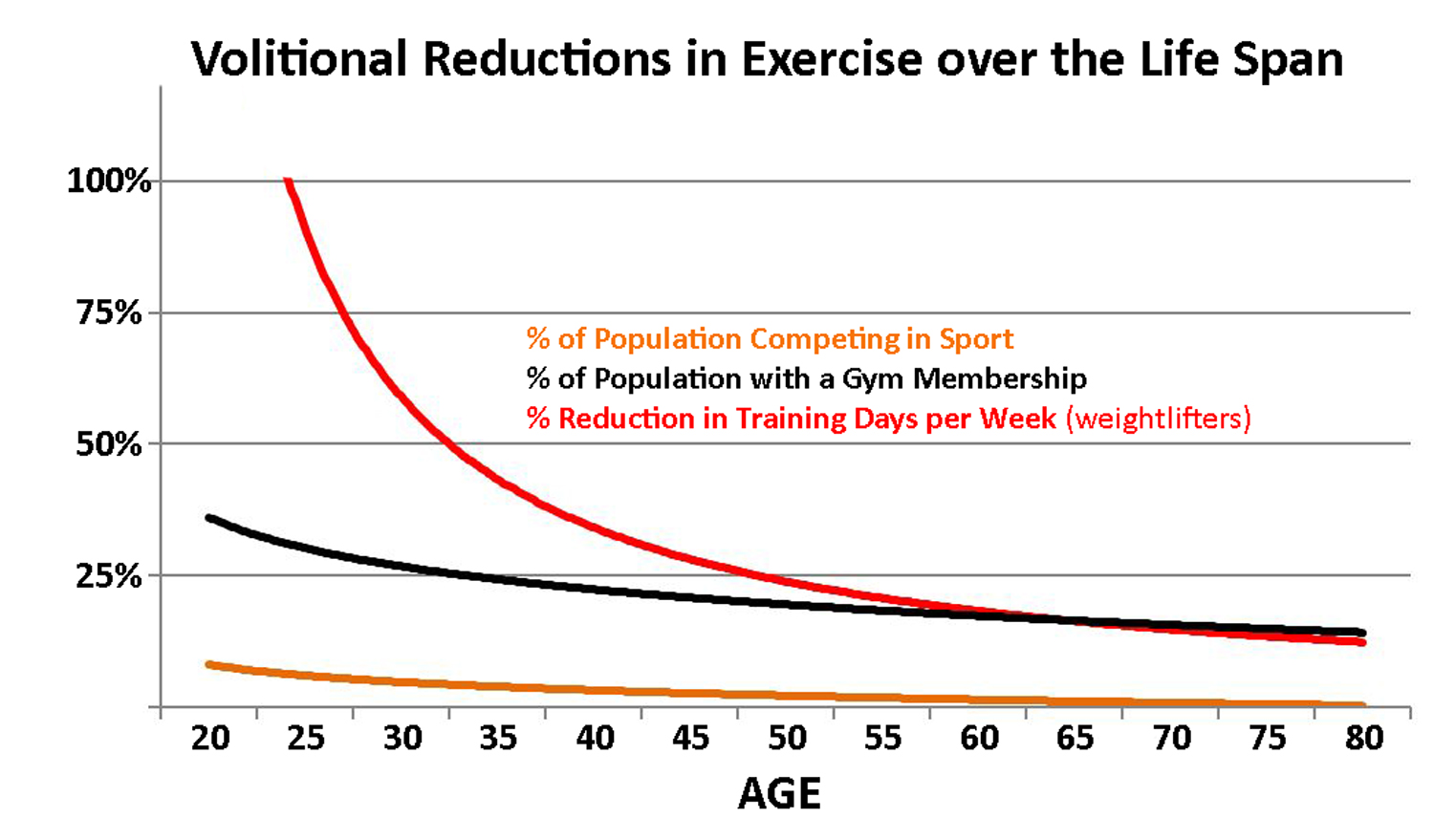

Figure 5. Competitive weightlifters train using higher volumes early in their career and much lower volumes later in life. The red line represents a data supported conjecture of how quickly training volume is voluntarily reduced over the lifespan of trained weightlifters. The “gym membership” and “competitive sports participation” lines indicate the rate of withdrawal from training at a gym and competing in sports with advancing age.

In elite competitive weightlifters the number of training sessions per week can be in the area of 15 workouts per week (Poletaev et al, Strength & Conditioning 17(1): 20-26, 1995) or more. If these workouts are on average two hours in duration, then the average elite competitor is training about 30 hours per week, nearly a full time job. That level of training volume is not maintained over a significant portion of the lifespan. By age 40 the number of training sessions per week has dropped to approximately 4.1 sessions per week, by 50 to 3.5 workouts per week, and by 60 workout frequency is approaching 3.0 per week (derived from Huebner et al, PLoS One 15(12): e0243652, 2020; Huebner et al, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(5): 2708, 2022). So specifically for weightlifters, it is likely the large reduction in training rather than the biological decay in organ systems function that drives the accelerated loss of strength in the post-50 years.

While it may appear that the obvious solution is to increase the number of training sessions in over 50 masters weightlifters, further analysis is required to determine the underlying motivations or other deleterious factors that led these middle-aged and older lifters to begin to reduce their training loads as they grew older. Balancing workload to an older person’s ability to adapt is not well researched and there is much unsubstantiated opinion in the press, and in classrooms.

Going to the Gym

Sports do not encapsulate the primary means by which the American public participates in physical activity or exercise; going to the gym, fitness center, or recreation center is the most common path chosen. About 21% of the USA population have spent money on a gym membership. If we break this number down into age ranges we see a steady decline over the lifespan:

| Age | Number of Americans in Age Range | Number of Memberships | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 21,000,000 | 6,300,000 | 30 |

| 25 | 22,000,000 | 6,400,000 | 29 |

| 30 | 21,500,000 | 7,100,000 | 33 |

| 35 | 21,000,000 | 6,100,000 | 29 |

| 40 | 20,000,000 | 5,200,000 | 26 |

| 45 | 20,000,000 | 4,300,000 | 22 |

| 50 | 20,000,000 | 4,100,000 | 21 |

| 55 | 20,500,000 | 3,600,000 | 18 |

| 60 | 20,000,000 | 2,800,000 | 14 |

| 65 | 19,000,000 | 2,800,000 | 15 |

| 70 | 16,000,000 | 2,600,000 | 16 |

| 75 | 11,000,000 | 1,200,000 | 11 |

| 80 | 6,000,000 | 800,000 | 13 |

Approximately 29% of younger adults from 20 to 44 years of age have memberships, but from ages 45 to 64 that number drops to 18%. In post-retirement years, 65 to 84, only about 14% have memberships.

While most people would consider everyone who goes to the gym to be doing something positive for their fitness and health, only 1 out of every 8 people you see in the gym are is likely training enough to keep or improve any aspect of fitness. This is definitely not the reality most expect.

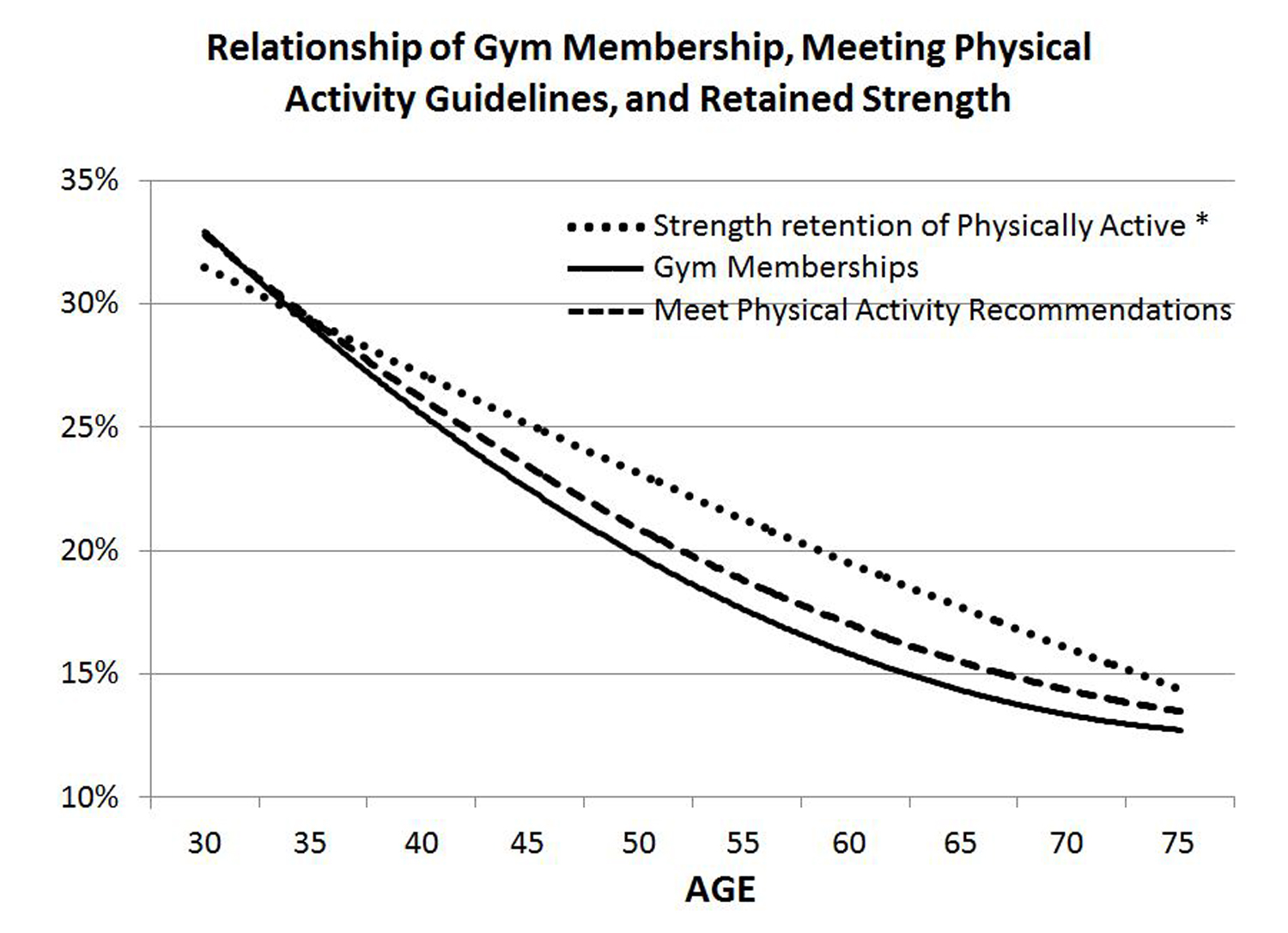

Figure 6. If we consider that those individuals who meet the Surgeon’s General recommendations for participation in physical activity to likely be the result of training at a gym or recreation center, then the lines should be roughly parallel. What we do see is that gym memberships and the percent of people meeting physical activity guidelines have a very tight relationship (solid line and dashed line). While there are statistical correlations, neither is tightly aligned to the loss of strength experienced by the physically active (dotted line). * Strength retention is expressed as a percentage of age specific weightlifting records; physical activity does not include programmed exercise or strength training.

What this data says, combined with the data on sports participation, is that Americans drop out of participation in sport and in gym attendance steadily. And this accrual of inactivity occurs in a manner correlated to long term losses in the strength element of physical fitness (endurance and mobility also decay).

Things may actually be worse than gym membership dropout data portrays (see figure 6). If we delve a little deeper into the data we find some disappointing characteristics of the training done, or not done, by those with gym memberships. Gym-goers train in a manner fundamentally different from competitive weightlifters or powerlifters. Across all adult age groups that purchase gym memberships, somewhere between 18% (Statista, 2021) and 67% (USA Today, 2016) of them never use them, ever. If we take an average of those two estimations, an average of about 42%, it turns out that only about 58% of people who have memberships actually go to the gym, and they do not necessarily go to train. Approximately 28% of those members who actually show up at the gym, do so specifically to socialize, not to train for improved fitness (Statista, 2020).

If we consider the previous data on masters weightlifters, where we see continued strength decline even with 3 or 4 workouts per week, doing less than that would be less effective at keeping strength levels up over the lifespan. And less than 3 to 4 workouts per week is precisely what the most active fraction of gym members does. After the first six months of training:

| Percentage of active members training less than 1 time per week | 43.7% |

| Percentage of active members training between 1 and 1.5 times per week | 27.6% |

| Percentage of active members training between 1.75 and 2.5 times per week | 15.3% |

| Percentage of active members training 2.75 or more times per week | 13.4% |

| (Data adapted from Fitness Industry Association, 2001) |

What this means is that over 71% of gym members do not do enough training to improve fitness or maintain strength. About 15% of them do enough to roughly meet the Surgeon’s General recommendations for physical activity. And only about 13% meet the requirements to be considered enough exercise to maintain or improve fitness.

Another consideration is that half of all gym memberships are cancelled by the member within the first six months after sign-up (IHRSA data, 2020). Even those memberships that last beyond the initial dropout still only average about 4.7 years in total length of membership (IHRSA data, 2020). Myriad reasons are reported as the motivation for dropping out quickly or after a few years; poor access, high cost, and low effectiveness at achieving goals are often touted as the primary factors. But before that, in getting older populations into the gym, barriers act to block motivation of older individuals to get off the couch. These individual perceptions can be boiled down to just a few. The most common reasons an elder chooses not to exercise or go to the gym are specious:

“I already get enough exercise”

“I say that exercise is important but I’m not doing it”

“I would go except I have a health issue”

(adapted from Biedenweg et al, Journal of Primary Prevention 35: 1-11, 2014)

If you aren’t doing anything, do something. If you’re doing something, do more.

Personal strength and fitness, and its biological mechanisms of attainment and maintenance, are not well described in the scientific literature, relative to cause and effect. Most research in the area sets about to discover some minute physiological phenomena associated to age-related decay, and there are some exceptional explorations on many underlying physiological mechanisms that are responsive to weight training. For example, research suggests that exercise can reduce the amount of cellular degradation. In one such study, telomeres (a chromosomal element related to cell survival) were degraded much less in older individuals who exercised versus those who did not (Tucker et al, Preventive Medicine 100:145-151, 2017). The average slowing of telomeric decay equated roughly to the older exercising individual having telomere structure similar to that of someone 9 years junior. There are multitudinous other studies correlating training with weights with some biological process. But we argue here that the voluntary reduction in volume and intensity of exercise noted with advancing age is the primary effector of strength decay, affecting all those underlying biophysical processes (after stopping physical activity or exercise long term) and which are now without stimulus for driving maintenance or functional improvement. Without the presence of robust physical activity or exercise there is no biological impetus to adapt positively, rather, the lack of stimulus allows negative adaptation to occur. Negative adaptation simply means the loss of physiological function or anatomical structural integrity.

In short, the vast majority of us need to do more than we currently are doing relative to physical activity or fitness in order to live longer, healthier, and better quality lives. This does not imply that aging is arrested by doing exercise, as some would like you to believe, the march of time never stops. But, it does mean that if you are older and are spending your life on the couch, you need to get up and move by doing anything active. It is imperative to note that the activity or activities chosen to engage in are ones that you enjoy. Enjoyment driven habit can help sustain your long term participation. The same advice holds for those that are currently physically active in some manner. Take it up a notch and start setting goals and purposefully exercising to reach them. Lift weights if you want to get or stay strong. Again, what you do as exercise should be a thing you like to do. The best type or system of exercise for someone, anyone, is the one they will actually do.

The author would like to thank the USA Masters Weightlifting organization, specifically Les Simonton and Michael Cohen, for providing the complete historical performance data for the entire membership of the organization since the masters program began (1975 to 2024).

Lon Kilgore earned a Ph.D. from the Department of Anatomy and Physiology at Kansas State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. He has competed in weightlifting to the national and international level since 1972 and coached his first athletes from a garage gym to national-championship event medals in 1974. He has also competed in powerlifting and currently holds several continental and world records, won his division in the first CrossFit Total event, was a decent high school wrestler, caught a number of crabs during his short collegiate rowing stint, was and still is a hack at golf, and was a regional fish cutting champion and competitor at nationals. He has worked in the trenches – as a qualified national-level coach or scientific consultant – with athletes from rank novices to the Olympic elite, and as a consultant to fitness businesses. He was co-developer of the Basic Barbell Training and Exercise Science specialty seminars for CrossFit (mid-2000s) and was an all-level certifying instructor for USA Weightlifting for more than a decade. He is a decorated military veteran (sergeant, U.S. Army). His anatomical illustration, authorship, and co-authorship efforts include several bestselling books and works in numerous research journals. His fitness standards for weightlifting and calisthenics have been included in textbooks and multitudinous websites. After leaving a 20-year plus professorial career in higher academia, his teachings can be found in vocational-education courses offered through the Kilgore Academy, and in articles like these.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

One Comment

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

A Conversation with Bruce Edwards on Metabolism, Community, and the Road to Health

Journal Club: February 5, 2026

When number-chasing replaces treating the root cause

Love this , thank you for sharing.