Summary

Greg Glassman, the founder of both CrossFit and BSI, discusses his views on the corruption and politicization of science. He shares personal anecdotes from his work in the fitness industry, along with explaining how his scientist father shaped his perspective.

Glassman became interested in probability theory as a basis for science after reading David Stove's book on philosophers Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend, and Lakatos. He shares his conversations with physicist E.T. Jaynes, who reinforced his beliefs, and Dr. Briggs, who helped him navigate problems identified in Stove's work. Glassman stresses the importance of connecting with thinkers who inspire him, as they significantly contributed to his knowledge and understanding.

Throughout the talk, Glassman cautions against the replacement of predictive strength with consensus when determining a model's validity. He uses his CrossFit experiences, which were often challenged by industry norms, to illustrate the dangers of such a shift in approach.

Glassman strongly advocates for a revamp of how science is approached and taught. He emphasizes skepticism, questioning, and independent thinking, seeing these elements as integral to the pursuit of scientific knowledge. He believes that experiential wisdom is key in complementing scientific knowledge.

His introduction to Briggs brings out a profound quote: "Chance is unpredictability, which is a synonym of ignorance, which is what random means," which helps underline the importance of understanding statistics, probability, and math. He views the turning of science into nonsense as a contributing factor to further corruption.

In short, Glassman perceives the corruption of scientific principles as a significant threat to the objectivity and validity of scientific knowledge. He underscores the necessity of understanding the predictive strength of scientific research and the dangers of letting consensus determine a model's validity.

In this speech, BSI and Crossfit founder Greg Glassman shares what he thinks is threatening scientific knowledge.

He talks about his background in science and what he learned from his scientist dad, Jeff Glassman, during childhood. Glassman then explains how these experiences led him to create CrossFit, a workout program. It was a massive success, but it was different from the usual approach to health and fitness. This made other fitness companies feel a bit threatened, which led some people to attack CrossFit.

Glassman became interested in something called probability theory - a different way to study and do science. He emphasizes that it's dangerous to ignore the power of predictions when doing any kind of scientific study. He also thinks that replacing predictions with simply agreeing on something messes up the facts and turns science into nonsense.

After reading a book about probability theory, Glassman began meeting with other experts to discuss these beliefs. It was very important for him to connect with thinkers who inspire him, because they helped him gain more knowledge and understanding.

The struggles of CrossFit and this demand for a better understanding of probability theory strengthens the need for a change in how science is taught and approached.

He ends by saying you should always ask questions, be skeptical, and think independently. He also believes learning from experiences is as important as learning from scientific facts. To sum up, he says that messing up science principles can be harmful and unfair, and stresses the need to understand the power of predictions in scientific studies.

--------- Original ---------

BSI and Crossfit founder Greg Glassman talks about the forces that are corrupting scientific knowledge.

Glassman discusses his background in science and what he learned from his scientist dad, Jeff Glassman, during childhood. Glassman then explains how these experiences led him to create CrossFit, a workout program. CrossFit grew really quickly and that caused some problems because it had an uncommon approach to health and fitness. Some established companies in the industry felt threatened by CrossFit's success, which led to attacks on the program.

Basically, CrossFit challenged the accepted way of doing things and got good results. That led Glassman to be interested in other unconventional ideas outside of fitness. He talks about a book on philosophers that changed the way he understood science. It sparked his interest in probability theory.

Glassman thinks it's dangerous to replace prediction with consensus when deciding if a scientific idea is valid. He sees this shift as turning science into nonsense and adding to the corruption of science.

He's now calling for a change in how science is approached and taught. He wants a greater emphasis on questioning, skepticism, and promoting independent thinking. He also stresses the importance of learning from experience in addition to learning from scientific knowledge.

His curiosity on the subject led him to connect with other out-of-the-box thinkers to discuss unconventional ideas about science.

Glassman warns listeners to not ignore the power of predictions in scientific research. He quotes a statement that basically means chance equals unpredictability, which is the same as not knowing, which is what randomness is. This is significant for understanding stats, probability, and math.

To sum it up: Glassman is pointing out that the corruption of scientific principles can threaten the fairness and truth of scientific knowledge. He emphasizes the importance of skepticism in science, the need to understand the power of prediction in scientific research, and the negative impacts of letting agreement determine if an idea is valid.

--------- Original ---------

Transcript

Greg Glassman: Good evening. How is everyone? How’s the food? Good. Any CrossFitters in here?

Crowd: *Cheers*

Greg Glassman: It’s good to see you again. Let me just touch up on a couple of things here. Some minor fixes, I don’t think science is broken, but I think there’s a lot of broken science. Okay. How much science is broken?

Well, I’ll tell you, most of it’s at the university. There are instances in pharma, in industry where science is broken, but typically when you see that you can find some kind of regulatory capture in a government agency. And the people are no longer in the business of providing remedies, but of assuaging the, the, the gatekeepers.

And in fact, Marcia Angell said she was 25 years editor in chief of New England Journal of Medicine. What was it, 2005? I think. She said that the regulatory capture of the FDA by the pharma industry was a hundred percent, and that nothing had come down from the FDA that wasn’t designed to, approved of, and originated at at Big Pharma.

So industry doesn’t have a lot of this problem. The natural sciences have very little of it, for the most part, where we’re looking at what we see, if you wanna talk departments, it’s where there’s primary research in psychology, sociology, some of the newer things like gender studies.

But I think the, the thing that’s so stressful, so devastating is that the, the epistemic debasement, and I’m gonna explain that, but the problem that has affected entire departments and entire fields has taken medicine as a victim. And that’s, that’s a bummer. You know, I don’t know what the expectation of, of experiments in psychology to replicate is and how much of a shock it would be to anyone to find that, that there was a lot in psychology that didn’t replicate, but to find that it’s true of oncology and hematology and other medical fields is, is stressful. Let me tell you a little bit about what got me here. It’s kind of funny if you think about it, but my involvement in terms of training and what I learned about science and science that works and doesn’t work, it began probably 30, 40 years prior to any interest in the subject.

And that was at home with dad. And in about 1960, we had a black and white tv. Everyone did, and it had a, there was no remote control. It had the rabbit ears, okay. Some of you remember that. But there was a Sensodyne commercial that was coming on, and it was on Bonanza and it was on you know, the, the fbi, everything we had on tv.

And it started at 9 outta 10 dentists, who recommend Sensodyne. We recommend a toothpaste, recommend Sensodyne, and by the time they could get to Sensodyne, my dad had run over and turned it down and would turn it and look at us, my mom and I and explain there’s no voting in science. That I don’t care what 9 outta 10 dentists think, I wanna know what the 1 in 10 dentists think. He would explain that innovation always comes from the lone to center. It’s not a group of people that come to you with committee with a new answer. It’s someone who’s that 1 outta 10 dentist. He goes, I wanna know what that guy thinks and why he doesn’t like Sensodyne and that would be more interesting to me.

He did that every single time, that commercial came on for a decade. My friends knew, they’d see the commercial. They’d go, “here we go,” and he’d turn up. And God bless him every time, he’d explain it. There’s no voting in science, none. It was like he had never heard it before. And so that was, that was part of my upbringing.

Then I got into school and of course, you know, I didn’t want to ever talk about what was going on. It’s science. Cuz no matter what we were doing, that’s not science. The old man was head of research and development, internal research and development at Hughes Aircraft Company for a couple of decades.

And he ran a lot of programs and he, the big thing he did was he would try to make scientists out of engineers and engineers out of scientists. And the biggest hurdle to that was teaching academics what science was so that more importantly, they knew what it wasn’t, and that’s what occupied his work.

I’m gonna jump forward now from 1960 to 1968 and I’m in the sixth grade and I was never much of a student. I like recess, CrossFitters, that’s what I liked, right. Go out and play. But we had open house and I don’t know if you know what that is, but it’s back to school night. But mom and dad come to school and they find out from the teacher what you’re all about.

It was nervous time to begin with, but, in the sixth grade, we go down to open house and my dad’s talking to Milo Johnson, my teacher. And Mr. Johnson explains, he says, we’ve been working on a science experiment for about three, four months now, and I don’t think Greg has done anything. And my dad looks at me in I, this isn’t good.

He didn’t say anything all the way home. And I, that made it even worse. And the following morning, he didn’t have anything to say. Later we talked and he says, what were you gonna do? And I was like, I was gonna, I had this box and I was gonna put a light in it and some rocks and some dinosaurs. It’d be like a diorama.

Isn’t that great? He goes, that’s not a, that’s not a science experiment. And I’m, yeah, it is. He goes, no, it’s not, not even close to a science experiment. So I’m like, oh, well that’s what I was gonna do. So he came home from work the following night and he’s got a box of a thousand nails that are one and a half inches, and he’s got a vernier scale micrometer in a box. And I, I have no idea what’s up. I, I couldn’t see this coming. So he pulls out the micrometer, and I don’t know if you know what that is, but it’s a little device you twist and then you read the Vernier scale and you could actually get to a 10000th of an inch, the length of something.

So we proceeded to measure a few of these inch and a half long nails, and we get, you know, 1.5 2, 1 3 and 1.4 9, 8, 6, 1. And he says, okay, you go now and go in your room and measure the thousand nails and write down each one that you, that you do, write it down and keep the biggest nail and the longest and the shortest.

And so I’m alright. So I went in my room, closed the door, and I got out my army men and I played for about 15, 20 minutes. Then I started just making up bullshit numbers, right? Writing ’em down so I can do this. They’re one and a half inches. I go a little to the left, a little to the right, a little to the left, a little to the right.

And I started kind of doing some mental arithmetic, which I didn’t have a lot of skill. I said, how long this should take? And I figured I need to sit here for a few hours cuz measuring the nails is really painstakingly slow. So I gave some lag time to make it credible and brought it into the old man.

And he sat there and played around, keeps looking at me, keeps looking at me. He says, you didn’t measure these nails? And I say, oh, yeah, I did, I measured them. Yeah. He says, no you didn’t. I go, I did. I swear I did. I measured them, every one of them, all thousand. And he says, no, there’s no possible way you did.

So I was like, wow. So he says, you gotta go back and do it again. So I cried, went back in my room, I figured he’d seen me. And so I pulled the shades out on my, on my, on my window. And I, and I stuck the towel under the door cuz maybe he’s looking under there. And I went back to doing my science experiment just like before.

And we, we, I, same thing. I come out and I’m like, did it? He’s playing with the numbers, looking at me, looking at me. He says damn it, you did not. I go, I did! He goes, you didn’t! I go, I did! This, this is my first exposure to scientific misconduct, by the way, as an active participant. And I sat there with the old man and it took seven hours to, and by now, this is like a 14 hour day, right?

And I’m 11. And when we were done, we got the most beautiful bell-shaped curve I’ve ever seen. Absolutely gorgeous. And he goes, this is what it looks like when you measure the nails, roll the clock forward 20 years, 25 years, 30 years. I got a kid in school and he’s supposed to do a science project. And he is not doing anything.

So I get a box of a thousand nails, but the micrometer was digital. It didn’t have a Vernier scale, it would just read it out. And I go, this sucks. This is easy. About an hour into it, Blake’s crying. He goes, daddy, do we have to do this? And he was so upset and I remembered how much fun it wasn’t for me. And I, I got soft and I couldn’t help it.

I let him go and I stayed up all night measuring the nails again. I had to do it again.

Yeah. Horrible. And the, and the school loved the project and he was getting all kinds of accolades and they’re asking him how he did it, and I’m just standing there feeling bad. It was all me. More scientific misconduct. Right. I liked recess and so my dad got me a job at Hughes Aircraft Company and I hated it.

It was fluorescent lights and there’s four dudes to a building and there’s no girls on the campus. And the whole thing was just bizarre. And I didn’t have the talents for it. It wasn’t my thing. And I got a job at a gym, cuz again, I keep telling you, I like recess, I like pe. But unwittingly, I brought a lot of what my father had taught me about science, about no voting, let’s define terms, let’s measure things, let’s do experiments. And I brought that mindset to the fitness space and created the fastest growing business in world history. Fastest growing chain in world history. 15,000 locations in about seven and a half years. Largely unintentional. Now here’s what happened.

I wasn’t trying to grow that. I wasn’t trying to grow that. But what I did do is I used the methods that I had learned from my father in terms of what science was and wasn’t. And I said, let’s do this. Let’s define fitness. And let’s start measuring some things and doing some experiments. And where that ended up is that constantly varied, high intensity functional movement, increases work capacity across broad time and modal domains.

That was the first kind of fundamental theorem of CrossFit. The success of that notion, the truth of that notion, the power of that notion created multi-generational wealth for me. So I, the nails paid off, I guess I got, I got more out of my fitness using my father’s methods than my dad did in terms of materially, you know, finding financial success and comfort.

It paid off, it paid off enormously but there, there was a reaction to it in, in academia, and the reaction was hostile. They sicced The New York Times on me, they sent reporters that were coming to do hatchet jobs on our little program. Never once did anyone take objection or issue with constantly varied high intensity functional movement, increasing work capacity across broad time and modal domains that got ignored.

The heart of it, the essence of what we were doing was never criticized. What they did was I saw things like the largest body of regulation internationally around exercise sciences, the International Confederation of Registers for Exercise Professionals. Their CEO announced in New Zealand that CrossFit had killed people in in the United States.

We sued them for it, of course, and the International Confederation of Registers for Exercise Professionals and the service address was at the Kellen Corporation in Atlanta, Georgia, the agency of of record. For the soda, big soda, food and beverage industry. That’s who had come out. They had set this organization up in proxy.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association, along with the American College of Sports Medicine, billed themselves as the academic twin pillars of sports medicine. One of ’em teamed with Gatorade and promoted hyper hydration. In a 1995 paper, they said that during endurance activities, athletes should drink as much as can be touched 40 ounces per hour, as much as can be tolerated.

And it killed a lot of people. Killed a lot of people. That’s the American College of Sports Medicine. Teaming up with with Pepsi, with Gatorade, did that handsome work. While Coke was forming exercises, medicine, a, academic plan to, and they, what they did is they infiltrated the affordable Care Act and got baked into that and would imagine what a surprise it was for me to find out is the largest thing in the fitness industry that up and coming is Coca-Cola.

And they are today the biggest player in in sports sciences through exercises, medicine. And we sent people to the certification, to the exercises, medicine certification and they went on for a full weekend. And my guys asked at the end, you haven’t said anything about nutrition the whole weekend.

And they go Very good. That’s right. And that’s on purpose cuz it’s outside of the ken of your field. Trainers, all you can do is offer up the, the U S D A guidelines. You can feed the pyramid, but you’re not allowed, you don’t wanna say anything else. You don’t wanna get off off the reservation in terms of the message.

And so what the next thing that kind of came along is one of these organizations published a study that had 16% of the participants being hurt in the CrossFit training. I knew immediately it was, it was, it was wrong. It wasn’t that the 16% that seemed super high and someone did something wrong, but what gave it away was that there wasn’t the 25% that won’t come back because they realize what, what hard work’s about and they weren’t there. And no one’s ever going to open up a bunch of CrossFit on a bunch of new people and not have about a quarter of ’em go, I don’t want to be fit.It’s not worth it.

See, the holy grail of my industry was, we promise you if you just sit there on the couch with the ThighMaster and watch TV five minutes a day, you’re gonna look like Suzanne Summers. Right? And it, it never isn’t really quite like that. The costs are much greater, like anything worth doing.

But this study was published and it it took off like wildfire and it got promoted and they went around the country talking about it. And so we sued them, said it was nonsense. And in discovery, we had been given some emails that showed there was a conspiracy to take CrossFit down, we got, we got our hands on that. And, the, National Strength and Conditioning Association said, no, there’s no way there’s none of that going on here. We showed the judge the emails we had, she ordered a forensic evaluation of their servers and there were hundreds of thousands and, in later phase of the suit, several million emails that were, that were responsive to our to our requests.

And what we saw in this email chain was the editor in chief of the National Strength and Conditioning Association, William Kramer, who’s just gotten a 30 year lifetime achievement award from the American College of Sports Medicine. He’s supporting the fabrication and falsification of data in the study. The researchers are telling him there were no injuries.

He says, I cannot publish this without injuries. You’ve gotta have injuries. So he came back. Two weeks later, he says, I got ’em. And he goes, now we can publish it. It now we can publish it. In deposition, there had been a whole bunch of lies told that the released emails revealed. We ended up getting the federal judge in the San Diego court to say that this is the most egregious behavior she’s seen in 25 years on the bench.

She pronounced them perjurors by name. She issued adverse inference sanctions that conceded the entirety of what we were after in our lawsuit, that they had fraudulently concocted this data, promoted it with an enormous effort. And then when caught lied in federal court over it and in state court, I called them soda whores and they sued me in state court.

We said, okay, well we wanna see all your exchange with soda. And they said, we don’t have any. And I go, I have some. And then the state judge ordered a forensic examination of their servers again, and there were, there were several million emails. With soda from the National Strength and Conditioning Association.

What was interesting at that point was that Lanny Davis, remember him, he called me at my home in Kauai, and I didn’t even know I had a landline. And it rang. I go, what the hell is that? And he was Lanny Davis, right? Effusive praise. He loves my work. He appreciates what I’m doing. He wants to talk about the NSCA versus CrossFit suit.

He’s representing no one in this, but he does have friends involved. And he told my attorneys that we would settle this suit the easy way or the hard way. My Manhattan White shoe law firm lawyer said, this sounds like a threat. And he says, no, no. You know how it works. Just, you know, you can settle or you can drag this all out.

But it, it was a threat. And what I’d done is I’d touched a nerve. I sold the company and It was, there was another part here from the, from what we’d seen, we started CrossFit Health and what we were doing there is bringing the people around that knew why it was that people became obese, what the nature of type two diabetes is and how you treat it.

Whole bunch of these issues, the, the role of statins their value, which is not good for, for treating of cholesterol. And these people are easy to bring around. And what I saw is that the problems that were inherent, that were, that were so profoundly disordered in academic fitness, were also there in academic medicine and it was shortly after that that I learned of the replication crisis in preclinical oncology and hematology where only 11% of foundational studies could be replicated.

These are studies on which clinical trials had repeatedly been conducted. So these are people that are sick with cancer. They’re, they’re clinging for the hope of this clinical trial. And the clinical trial never had a chance of doing anything for them because the science wasn’t there. Now, that’s a problem, I think, that’s a problem.

Let’s talk about, let’s talk about, about broken science. I didn’t pick the language, the term broken science, I got that from Google. A lot of people have written on the replication crisis and the problems in academic science. And that term has been used, and I like it, it works. We played with other terms. It’s a, it’s a debased science. It’s consensus science. It’s found in the academy. It only appears in peer review. It’s perverse. But the, but we stuck with broken cuz it’s been in use and some smart people have gone there. But I really like the notion of corrupt.

But I want to, I want to be clear about this. There’s two definitions of corrupt. There’s a corrupt that’s corrupt, one in most dictionaries is dishonest or unethical behavior for personal gain. There’s a second corrupt definition two, and this one is an alteration of former structure to, to impede function like a corrupted computer file.

Here’s what’s happened in academic science. It has been epistemically corrupted and that has left the door open for the other kind of corruption in rather dramatic fashion. I say it’s not unlike, imagine running a bank where you’re open five days a week, Monday through Friday, and you got a security guard while it’s open, and then someone decides that let’s be open on Saturdays too, but they don’t make arrangements for a security guard and, just think, bank starts getting robbed on Saturdays, right?

That’s what’s going on in academic science. The epistemic debasement. I’m gonna talk about that. But that, and I think I can, I think I can get it across so that everyone here has a good sense of what it is I’m talking about. But that epistemic debasement made the ethical and moral corruption. The first corruption made the second one, ineluctable, certain. There was, there was, there was no way it wasn’t gonna happen.

Now there’s a lot of literature on replication and on broken science, but in this, you don’t see enough discussion as to what science is. And so I’m gonna do that now, and I think we can do it very simply. And this is a, I’m gonna call this modern science, and I’m talking about the science of Bacon that delivered Newton and Laplace and all that kind of stuff.

And we need a term for the science that doesn’t work. I said broken. Several people that I have immense respect for Keith Winshuttle and and Roger Kimball have referred to the science that won’t replicate the academic science is postmodern. I kind of like that. It’s got its own kind of dig to it.

And there’s probably some awareness here of issues with post-modernism in, in the academic world, but whether we call it university science or, or post-modern science or broken science, I wanna contrast that from what I’m calling modern science. And I think we need to talk about what it is that’s broken before we look at the break.

So I’m gonna walk you through very simply how science is supposed to work. Okay? And I’m gonna play with four words here. I wanna talk about observation, measurement, prediction, and validation. All right? Stay with me. An observation is a registration of the real world on our senses or sensing equipment.

Easy enough, right? I see you with my eyeballs. If I can tie that to a standard scale with a well, well-characterized error, it becomes a measurement. Which also constitutes in science a fact. Okay, so I’ve got an observation, registration of the real world, and my senses or sensing equipment. I tie it to a standard scale with a well-characterized error, and now I have a measurement or a fact.

And if I take that fact or a measurement and I map it to a future unrealized fact as a prediction, I now have a model, a scientific model, and it is a forecast of a measurement. I take a fact and I map it onto a future unrealized fact, and it finds validation from its predictive strength. And we rank these models.

There’s four flavors. They’re graded and ranked by their predictive strength, and that’s conjecture, hypothesis, theory, and law. All right. So an observation becomes a measurement when tied to a scale measurement becomes a, it stands as a fact. We map a fact to a future unrealized fact. We have a prediction, and the validity of the thing is determined by the predictive strength.

Conjecture is an incomplete model, typically an analogy to another domain. It’s like when Claude Shannon first thought that information had entropy, just like physical things in the universe, and then later developed that theory. At first, it was a conjecture explored and demonstrated to miraculous effect.

A hypothesis is a model that, that based on all of the data in its specified domain, containing no counter examples, incorporating a prediction of an unrealized fact. Easy enough, right. Hypothesis. I’m gonna do that one again. It’s kind of the, the heart of this. It’s a model based on all of the data and it’s specified domain incorporated with no counter examples. Incorporating a novel prediction of an unrealized facts. Okay. And a law, the next step, the, the highest one, is a theory that has received validation. Received validation in all possible ramifications to known levels of accuracy. So we’ve just moved from an observation to a measurement.

To prediction and validation. And now prediction is, is a model, is a scientific model. Now I wanna talk about some of the kind of features of that that I think are five criteria that are pretty important. One, modern science is source and repository of, of objective knowledge, source and repository. It comes from there and it’s stored there.

Where does it store? It’s siloed in models, conjecture, hypothesis, theory and law. Just like we talked about, the models map a current fact to a future unrealized fact as a prediction. I’m repeating myself here, but it bears repeating and thinking about predictive strength is the sole determinant of validation.

That’s it. Which means that validation and method are entirely independent. So the truth of it is, is that when my, my model, my theory, whether it comes from inspiration or perspiration, it’s validity is determined not from once it came. But it’s predictive strength. So if you, if Einstein had the dream e equal mc squared, or he saw it in the, in, in his goldfish bowl on the bottom. It doesn’t matter. The source doesn’t matter. This kind of, you know, for those of you kind of philosophically include, this is when I hear Paul Feyerabend say, there is no, no scientific method. There’s almost a, kind of a truth to that. The method is baked into the definitions, into the, into the meaning.

Okay? Now, from here,

what I want to do is some further criteria from this. The process is inductive, where conclusions follow from premises with probability and not certainty. That’s very important. You see a lot of different definitions of induction compared to deduction. And you know, for Hume, it was from the seen to the not yet seen.

I really like what Martin Gardner offered up in terms of a definition of of induction. He said induction is where the conclusion, the conclusions come from the premises with probability, with deduction, it comes with certainty. And I think that works, that works very effectively. Here. We’re we’re validating these theories, these models on their predictive capacity.

Their predictive capacity is a measure of probability. It is an inductive process. The clear demarcation of science from non-science is the predictive power of its models. It’s very important. So you can stand up in front of a group of people, I half thought of doing that here tonight, but it’s not, not everyone enjoys the process so much, but you can ask a whole group of people in the sciences, from the sciences what science is and put it up on a board and I’ve seen this done.

And then you can ask, well, astrology and astronomy, let’s go through your list. And invariably what you’ll see is that no one offered up the significance of the predictive strength being the validating demarcation. And so that, that absent the list just about anything someone thinks science is to explain things to how the universe works, advance our education.

The astrologist, standing there nodding, go. Yep, yep, yep. The problem with astrologer is that you can’t make a statement about Aries that shows to be valid. You can’t, you can’t predict things effectively with it. All of our scientific knowledge is the fruit of, induction, validated by predictive power.

Predictive power is the sole source of rational trust in science. That’s it. That’s all there is. And in fact, if you think about it long, I think that we trust everything on predictive power. Your kids, your spouse, your insurance company, your doctor, right? And they, you evaluate by the same thing. Their trust in you is based on that predictive power.

Let’s talk about, let’s talk about breaking this model that we just gave you. Okay. Let’s look at that, I’ll tell you what’s happened in academic science. The inferential statistics, that is the frequentist statistics that has given us null hypothesis, significance testing and confidence intervals. And you’ve seen that in so many studies.

That inferential statistics does not admit the meaning of the probability of an assertion. What they say is that probability can only be of data and not of an assertion that an assertion like all propositions has a value, true or false. The academic science has deduct his roots. That wasn’t done by accident.

That was done very, very deliberately by Karl Popper. Hume was responsible for this start. His, his inductive skepticism. Hume believed that that induction couldn’t give couldn’t return certainty. He was exactly correct. It cannot, so what move on, what wasn’t accepted is that, is that validation comes from the probability from the, from the, the predictive strength.

But this science that uses a null hypothesis and significance testing and confidence intervals denies the meaning of the, of the probability of the proposition. And so the inferential statistics in the work never get around to the probability of the hypothesis of the, of the thing. And what you’re going for is a low P value, right?

A good confidence interval. And to get published in the right journal and we’re off to the races, I’m gonna share with you an expectation of replication in that system is irrational. An expectation of replication. It’s, it’s exactly what should happen when you flense validation from the scientific method and replace it with tools of consensus and a, and a and a rather absurd inferential statistics.

There’s been a 70 year battle to fix P values, and is there any progress being made? You know. Yeah. But I would recommend looking up a guy named Gigerenzer, just like it’s spelled from Max Planck Institute. There’s a guy Charles Lambdin from Intel Corporation who in, in 2012 said, this is sorcery.

Science is empirical, and p values are not. We had a guy named David Bakan, in 1966, Say that, that, that the mischief that’s, that’s afoot is unbelievable in the field of psychology. We had Sir Harold Jeffreys in 1939 on P-values, and I just love this. I think it’s the funniest thing ever said in statistics, which is not a hard thing to do, but it is the funniest. He said, in summarizing the P-values and he’s very correct, he says, a procedure that rejects a hypothesis, even though it may be true because it failed to predict things that never happened. He goes, Hmm, that’s an amazing process. And he saw it for exactly what it was in 1939. And it’s still an amazing process, but of course the science won’t replicate.

There’s no pressure for it to replicate. There’s no, there’s nothing in the method that would, that would cause it to replicate. There’s there’s no recognition of replication. It’s just a, it’s just a crisis when it’s discovered that things won’t replicate. Now I wanna, I don’t, I don’t wanna dwell on, on the replication stuff cause you can find a lot of that.

But I do wanna tell you to, I wanted to have you take, and I wanted to leave you with something tonight, you could do something with and build on. So I want you to think, and all this is available online, and so with the notes I got, but I want you to play with me with this observation becomes a measurement.

A fact tied to a future fact is, is a prediction. And that validates through its predictive strength. And I want you to look at that. And then there’s a handful of, of conundrum dilemmas, problems, debates around the philosophy of science that are well known.

And I’m gonna send you to Wikipedia of all damn places to look at. And I, I love it cuz, cuz I hate Wikipedia more than anybody. All right. You know, so many people think that the social media censoring started in this covid era. It didn’t. Everyone that was willing to speak truth to power about statins and the nature of heart disease found themselves delisted from Wikipedia.

They were removed. And these included some of the, some of the most important scholars in the world on these topics. And so I had a little ax to grind with them, but I, no one hates Wikipedia more than I do, and no one recommends articles of Wikipedia more than I do, but I’m usually wanting you to go there to see how messed up it is.

You won’t believe this. Look how they got this wrong, but I got a handful of these that I’d like you just to explore. And one of them is the demarcation problem. You learn there in the first sentence. This is a 2000 year old problem. Well, I’m gonna solve it in three seconds. Popper was wrong.

Falsification is not the demarcation. Falsification would be necessary for a scientific assertion, but, but not sufficient. And what he did is he took the Vienna circles of the logical positivist. It was Ayer who said that falsification was a requirement for a meaningful assertion.

But science delivers way more than meaningful assertions. Like Aries are beautiful, is a, is a meaningful assertion, true or not, is a different thing. What what science has to do is has to have, have theorems that have predictive value. And so you go to the article on the replication crisis and a demarcation rather than you see it in.

So you go to the replication crisis. And again, why would this stuff replicate? There’s no force for replication. The essence of validation has been removed from academic science and replaced with consensus being published in the right magazine and getting that p value. Another one, interpretation of probability.

First, let’s go, let’s go to it’s a foundations of statistics, and that’s a, that’s a great little article. And they say that. It’s unanimously agreed, just starts like this, that the foundation statistics lies in probability theory, but the meaning of probability is never since the Tower of Babel has there been more debate on and confusion around something than there is on the meaning of probability.

Interesting. You go to the meaning of probability and they, they talk about this being an ancient debate, several hundred years old, not ancient, but several hundred years old. And the issue is this, that does probability inhere in the object or is it a measure of our, of our knowledge? And you might look at the penny and say, is the 50 50 of the coin toss or the one in six of a die?

Is that, is that baked into the object or is it a reflection of, of our knowledge and. We know, and it’s not an easy thing to learn, but we do know that probability is, is a objective measure of your level of knowledge. And Dr. Briggs has a great demonstration of that, that he did for us in Phoenix.

Go to scientism. That’s another fascinating story we learned there, that there’s things that look like science. There’s two kinds of scientism. There’s one of having a overarching crazy faith in it and treating it like religion. And there’s another scientistism that’s kind of the faking of it. You got the lab coat and the computers and all that stuff, but what’s really what’s happening is not science that will resonate with you, if you look at that.

Science wars. Meta science. This is largely John Ioannidis offered it using research methods to analyze research. And there’s all this gnashing and worrying and talk, and, but nowhere is it defining science, which is kind of interesting. Makes it hard. And of course the article on scientific method.

Now, what’s the solution here to this, this science that won’t replicate? I don’t know. I don’t, I don’t really think that way, but what I would like to see done in, in other words, I don’t, I don’t see a mass conversion event. I don’t think this is gonna be fixed, at least not any time soon, but what I do think we can do is provide resources and tools to protect individuals from the tyranny of fake science and its purveyors that I think we could do.

I don’t think it would be too hard to give enough education to ninth graders that someone says, ‘if you don’t believe what I’m saying, you don’t believe in science’ that should make kids laugh. Right? Science isn’t something we believe in or when someone talks about the science, right? You may have the science, you know, you’re on that, on that wrong track.

What I would propose we do is take Hume, Pearson, Fisher, Neyman, Popper, Lakatos, Kuhn, and Feyerabend, especially Popper, Lakatos, Kuhn, and Feyerabend, what David Stove called the four irrationalists. These are the guys that said science is deductive when it’s not. These are the ones that denied meaningful, trustworthy knowledge coming from induction.

It does. But I would replace them with Bayes, Laplace, Pólya, Jeffreys, Cox, Shannon, Jaynes, and Stove, whether you know those names or not, you can look ’em up online, we’ll send you to ’em. But what’s interesting, the substitution takes from academic science, five philosophers and three statisticians. And by the way, the three statisticians that are involved in academic science, Pearson, Neymann, and Fisher, they would be aghast to see what had been done with their work.

They were competing views of the world and it was psychologists in journals and textbook writers in statistics for psychology that took a hybrid chimera of these two opposing views and formed them into one that doesn’t do anything for anyone.

And it’s not even recognized by statistics or mathematicians, that’s null hypothesis significance testing. It’s an aberration of the social sciences in academia and unfortunately medicine. But what we’re doing is we’re trading five philosophers and three statisticians for four physicists, two mathematicians, the father of, of information theory and one philosopher.

The good guys list again is Bayes, Laplace, Polya, Jeffreys, Cox, Shannon Jaynes, and Stove. And in that group, what we have is a probability logic that is the, is the fabric, the structure of the logic of science. And I believe that we can teach this to children to seventh, eighth, and ninth graders to enormous benefit. The idea of teaching, I think teaching the trivia of science.

You know, look, look at what a survey course in science looks like, right? We spend a, you might spend a week on a periodic chart, and then you go to the, we go to the solar system. We might take some styrofoam balls and spray paint ’em and put ’em on coat hangers and build them to scale, right? And then you get into biology and we’ll do a week of photosynthesis and a few days of respiration and compare the plant and animal kingdom and move on.

I think ahead of any of that, what we need to do is teach kids philosophically what science is and what science isn’t. And it’s important for, it was for engineers, a Hughes aircraft company, and it is for our children. It is for people’s future science education. If you hear an anti-science message in here, you’re not listening clearly. Science is source and repository of man’s objective knowledge. It may be the crowning intellectual achievement of the human race, but there’s a problem and it can’t be ignored. And when it manifests in oncology and hematology when it invites this wave of corruption that finds it so easy, you know how, look, imagine from soda’s perspective, I either have to find some, create some science that shows that sugar’s good for you, or we need to find a scientist and get some good p values and published in the right magazine.

And they’ve found that easy to do, easy to do. The force that soda and the food and beverage industry in, in total plays on our lives and our healthcare and our public health is enormous. Is enormous. Any questions? Thank you.

Crowd: Negative effects of discrimination and kids. Okay, but you’re not going to find a study about the positive results of good parenting and kids. There are certain subjects which are not being studied and to, to increase our awareness and frankly to maintain traditional culture. Because so often it’s what used to be done is what needs to be done in the future. So I just wonder what you would comment on that.

Greg Glassman: Yeah, if I make a list of the things most important to my life most of ’em are not amenable at all to any kind of inputs from science. My love for my children, my love of country my trust of, of my, of my family and wife and loved ones, my friends, and none of these things.

I used to say, Hey, I’ll go to the, I’ll go to the town debate on free speech, but I’m bringing my gun in case I lose, you know, I mean, right. I, there’s, there’s a, there’s a lot of things that are really, really important and don’t come within that sphere. I think it’s important what we eat, but I also think that handing out surveys and then following up on people five years later, I don’t think that’s really doing science.

What’s the problem there? Well, this process begins with an observation of the real world. Answers to a survey aren’t observations of the real world. I’m sorry. That’s a, that’s an entirely man created thing. And I’ve got your memory, your honesty, all these things as factors here. And when my dad saw the Framingham and Harvard Nurses study, he’s like, God, they didn’t even measure anything.

They didn’t, they didn’t. And this is, you can, you can level this charge to almost all of of nutritional epidemiology. And I would be so bold as to say that kind of probably with Douglas Murray on this, that I think that there’s probably been a better contribution to- say guys I’m gonna make myself unpopular here, I should have walked off a little bit ago. But it may be that Shakespeare’s given us more insights into psychology than psychology has as a science. And maybe these things, maybe these things just really aren’t sciences, but still important. I’m willing to admit that. So that’s where I, I kind of go with that.

I understand what you’re saying, but I’m glad I’m not in that field. But it is. The social sciences are, are supremely affected with this, with this malady and I, but I’m gonna, I’m gonna give this psychologist this, it started with them. It was, it was they and their, and their statistics book writers that, that got this whole null hypothesis thing rolling.

But the psychologists spoke up first and loudest about the problem. Those guys would be commended for that. Like Gerd Gigerenzer, I mean this guy, every five or six years, he writes another brilliant paper, the same thing. This thing’s gotta stop. We gotta stop it. The people that took exception to null hypothesis significance testing, were saying this would lead to a replication crisis long before it was observed. That includes my dad.

Crowd: Yeah. My question is, if you believe that the corruption of science is fundamentally connected to the politicization of science, science fundamentally just means knowledge. But knowledge in the search for knowledge is to question authority. But as science attempts and, and people calling themselves, scientists attempt to seize authority for themselves.

Then they can no longer be skeptical because you have credentials, you have peer review. I’m honored, I’m someone important and you should listen to me. But it seems that that spirit of, of scientific inquiry is incompatible with authority simply that you, you have to have some sort of division there.

I wonder what your thoughts were on that question.

Greg Glassman: You know, which do you think would be an easier task to sell a BS theory of gender origins to a gender studies professor or to convince Elon Musk of a rocket field that didn’t really work. In industry and technology the demand for deliverables keeps everyone honest.

And what’s interesting is that they don’t do a lot of philosophical discussion. And, and oddly it’s not needed because of that demand for deliverables. And this is what got Serawitz to say from a University of Arizona. He said science was in its senescence, which was interesting. And his solution was, this is a socialist is more government involvement, but he thinks it all should be tied to product development, to deliverables, to tangibles and not tenure and labs and, you know, publication.

But I wanna remake the point that the epistemic debasement and removing predictive strength as the validating factor is just like sending the bank guard home every Tuesday at two o’clock. You’re gonna get robbed at three o’clock on Tuesday. That’s what’s gonna happen. And so it was ineluctable, it’s fertile grounds for the first corruption.

I don’t, I I can’t say too much more about that. I don’t think. I think I’m beating a dead horse.

Crowd: Why were they after CrossFit?

Greg Glassman: I’m sorry?

Crowd: Why were they after you and CrossFit?

Greg Glassman: Well, you know, I understand RFK Jr was here recently, and Murray Carpenter wrote a piece on me in the Washington Post and he said that Glassman’s at war with Coke and winning.

And my life changed after that. And RFK called me and to tell me good work. Nice way to go. You remind me of something. I know you’re not asking this, but I want to, I want to offer it anyways cuz I got a chance to

it’s too, too far down the rabbit hole. Did I answer that at all?

Crowd: Go for it, go for it!

Greg Glassman: Repeat your question again. Let me see if it sparks that same

Crowd: Why were they after the CrossFit.

Greg Glassman: Yeah. We were speaking truth to power and we had the fastest growing chain in world history and we were one at a time bringing people over to, to the light. And it, it made the, it made the whole thing a problem for, for people.

Brett Waite: Yeah. We will take one more question before the next speaker. So

Crowd: You talked about there need to be an objective view of the world, but I’ve seen that there seems to be a replacement in some of the literature of the word nature with the word science. To me, that seems like it’s a shift from it becoming more authoritarian, not looking at the objective world, but * Unitelligble *

Greg Glassman: Certainly when you see the science. Right, right.

Yeah. I’m gonna, I want to introduce Dr. Briggs here. I read, I read David Stove’s book on Kuhn, Popper, Feyerabend, and Lakatos, and now Broken Science, we own the rights to that book. We’ve got that for a penny. And I think it’s one of the most important things written on science in the past a hundred years, perhaps.

And when I was finished reading Stove, I felt convinced that probability theory was where science grounded. But I, I didn’t know any probability theory, but I assumed that if I went over to the other side of the, of the world and looked at probability theory, I should be able to find people that thought that’s where Science grounded.

And in fact, I did in E. T. Jaynes. And he was one of these superstars, the physicists that I would put in the pantheon and replace one of these, these wacky philosophers. But from Jaynes, I started typing into Google looking for strings of things. Like I said, that Stove talked about a problem with modus tollens in the offering that if, you know, in modus tollens is, is if a, then B is one premise and then not B is a premise, second premise and then the conclusion is not A, right. And stove had observed a a problem seemingly with “if baby cries, we beat him. We don’t beat him so he doesn’t cry.” And you know, everyone’s had a kid knows where that fails on a lot of levels. But I put that into, I put that into Google cause I wanna go, who else has seen this?

And this man comes up and I send em, what was my lead on all of this for reaching out to, to I, I’ve done something wonderful here. Rather than waiting for the smart people to come around like I did at CrossFit what I did was I went and found all the people that had mentored me through their works in writing.

And I contacted him and I hit him up with this. I said when science replaces predictive value with consensus as the determinant of a model’s validity, science becomes nonsense. And Matt’s response was, you think, and I, and I, I knew I’d, I’d found a soulmate, but I, I call him my math teacher, but I’m gonna leave you with a sentence here that I think is, I think is the most profound thing ever in this whole rarefied space of statistics, probability, and, and math .

I, I have to, I have to bring it with me to remember it. It’s so hard to remember, but you keep reading on this and look at it, and it just gets better and better and better. And it’s one of the smartest things ever said. And it’s chance is unpredictability, which is a synonym of ignorance, which is what random means.

And I, I’m not gonna play with that here. I’m gonna leave it for you to do, but you can find it on our website, Matt. So, but I invite you to read uncertainty. If Matt had died, he’d be on my list of, of of dead guys we should all be following in science. But I think he, I think he is a very important living philosopher.

I have immense respect for the guy. And with, with great honors, I’m gonna introduce you to, to Matt Briggs.

Thank you.

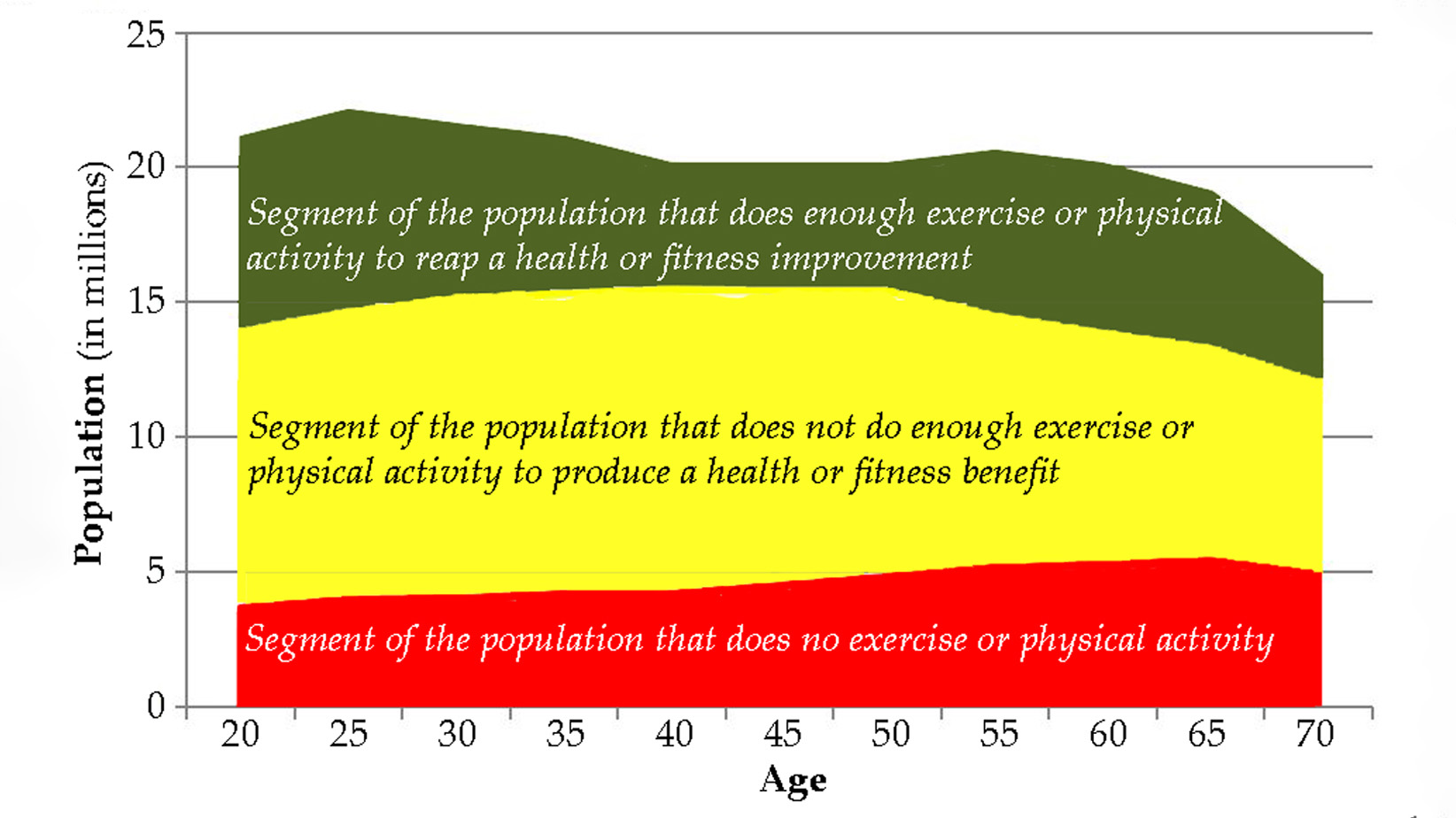

Greg Glassman founded CrossFit, a fitness revolution. Under Glassman’s leadership there were around 4 million CrossFitters, 300,000 CrossFit coaches and 15,000 physical locations, known as affiliates, where his prescribed methodology: constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity, were practiced daily. CrossFit became known as the solution to the world’s greatest problem, chronic illness.

In 2002, he became the first person in exercise physiology to apply a scientific definition to the word fitness. As the son of an aerospace engineer, Glassman learned the principles of science at a young age. Through observations, experimentation, testing, and retesting, Glassman created a program that brought unprecedented results to his clients. He shared his methodology with the world through The CrossFit Journal and in-person seminars. Harvard Business School proclaimed that CrossFit was the world’s fastest growing business.

The business, which challenged conventional business models and financially upset the health and wellness industry, brought plenty of negative attention to Glassman and CrossFit. The company’s low carbohydrate nutrition prescription threatened the sugar industry and led to a series of lawsuits after a peer-reviewed journal falsified data claiming Glassman’s methodology caused injuries. A federal judge called it the biggest case of scientific misconduct and fraud she’d seen in all her years on the bench. After this experience Glassman developed a deep interest in the corruption of modern science for private interests. He launched CrossFit Health which mobilized 20,000 doctors who knew from their experiences with CrossFit that Glassman’s methodology prevented and cured chronic diseases. Glassman networked the doctors, exposed them to researchers in a variety of fields and encouraged them to work together and further support efforts to expose the problems in medicine and work together on preventative measures.

In 2020, Greg sold CrossFit and focused his attention on the broader issues in modern science. He’d learned from his experience in fitness that areas of study without definitions, without ways of measuring and replicating results are ripe for corruption and manipulation.

The Broken Science Initiative, aims to expose and equip anyone interested with the tools to protect themself from the ills of modern medicine and broken science at-large.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio

Maintaining quality of life and preventing pain as we age.