A two-part series on weight loss drugs and food policy

By Maryanne Demasi, PhD

There’s no easy solution to weight loss, despite what drug companies might have you think. Weight loss medications have a long history of successive failures. Many of them begin with great promise but often don’t live up to the hype or end up discontinued because of serious side effects.

Recently, intense media focus on obesity and diabetes drugs like Ozempic, Wegovy, Saxenda, and Mounjaro has been fuelled by celebrity endorsements causing some manufacturers to struggle to keep pace in the face of soaring demand.

But are these “miracle” drugs or merely a band-aid solution to the obesity crisis?

In this two-part series, I speak to experts in metabolic health and food policy about the latest evidence for these medications and explore ways to address the root cause of the problem.

The medications

They’re known as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1ra), which mimic the GLP-1 hormone to signal a feeling of fullness. It does so by slowing the clearance of food from the gut, leaving the person feeling fuller for longer.

The degree of weight loss is similar to that seen after weight-loss surgery and is accompanied by improvements in blood pressure and blood sugar levels, which helps people with diabetes to manage their condition.

The drugs are typically self-administered weekly through injections to the belly or thighs. Semaglutide is the active ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy, liraglutide is the active ingredient in Saxenda, and tirzepatide is the active ingredient in Mounjaro.

Do they really work?

The simple answer is “yes” with a caveat says Mark Cucuzzella, an obesity and metabolic health physician and professor at West Virginia University School of Medicine.

“The drugs can bring about modest weight loss, but who should be prescribed these drugs, for what indications, and for what long-term outcomes, are the real questions,” he says.

Several years ago, Cucuzzella began using the drugs sparingly in severely diabetic patients who were significantly obese, had a poor relationship with trigger foods, and at high risk of heart disease.

But recently he noticed something different about the patients being referred to his clinic.

“I began seeing patients who were metabolically healthy and wanting to take the drug just to lose a few pounds,” says Cucuzzella. “People need to understand that the drug comes with significant downsides and therefore, should only be used in the highest risk patients.”

Cucuzzella explains that because the drug slows the movement of food through the gut, it can lead to great discomfort. It sends a ‘satiety signal’ for some, but for many it leads to nausea.

“The drug makes many patients feel miserable. They get nausea, they don’t enjoy food anymore, and this is particularly bad for children. What are we teaching young kids about their relationship with food?” says Cucuzzella.

His concerns stem from the recent push to prescribe these medications to young people, driven by the increasing prevalence of childhood obesity, which has quadrupled in the US since the 1980s.

The American Academy of Paediatrics, for example, issued its first comprehensive guideline calling for more aggressive treatments for children and adolescents with obesity, including pharmacological interventions.

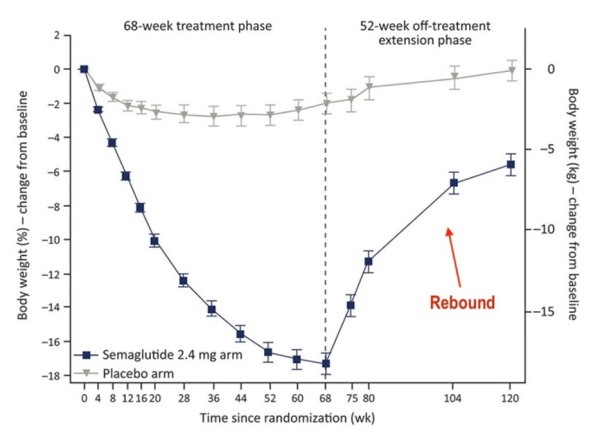

“The trials in kids were conducted for only 68 weeks,” says Cucuzzella. “What happens to these children five years later? There is no long-term data. And what happens once they stop the drug? We saw in the trials that there was immediate rebound of their weight.”

He adds, “We are seeing mental health sequelae too. What happens to the relationship with food in the youth prescribed these meds? My hypothesis is that it will not be a positive one.”

Now, the drug makers have announced that they are testing the drugs in children as young as 6 years old.

Cucuzzella worries about the mass prescription of these life-long drugs and wants to see a more judicious approach to prescribing.

“For diabetes patients on big doses of insulin who are massively insulin resistant and have a bad relationship with food and at high risk of early mortality, the drug probably has a net benefit,” says Cucuzzella.

But he also stresses that we need a better way to empower citizens early in their life to own their health despite the huge influence of Big Pharma and Big Food.

“The cost of these drugs for all who meet the ‘criteria for therapy’ is unrealistic,” says Cucuzzella. “In some ways this is another strategy for the Medical-Industrial Complex to further control you….lock you into to needing the assistance of doctors, pills, and medical testing for your whole life.”

The downsides

• Stomach paralysis

The US Food and Drug Administration has received reports of patients experiencing severe gastroparesis, or “stomach paralysis,” in which digestion of food slows significantly, potentially causing severe vomiting and nausea after taking these medications.

The American Society of Anaesthesiologists has also warned that patients should stop taking GLP-1 drugs days before surgery to reduce the risk of regurgitation and aspiration of food into the airways and lungs during general anaesthesia and deep sedation. They found that even though patients were fasting before surgery, their stomachs still contained food on the operating table.

The FDA has also said that symptoms of stomach paralysis are reported to persist even after patients have discontinued their medication.

A 44-yr old Louisiana woman has filed a lawsuit against the drug manufacturers for failing to warn of the risk of severe gastrointestinal events. After taking Ozempic and Mounjaro, she claimed she was hospitalised for stomach issues involving “visits to the emergency room, teeth falling out due to excessive vomiting, requiring additional medications to alleviate her excessive vomiting, and throwing up whole food hours after eating.”

• Muscle loss

Weight loss (~16%) in adults and adolescents over 68 weeks, consisted of an almost equal amount of loss in muscle mass, which some doctors say is “alarming.”

The problem is two-fold. First, muscle is essential for metabolic function. Skeletal muscle is mainly where your body processes sugar, so you don’t want to reduce that metabolic ‘sink’.

Second, when the person stops the drug and their weight rebounds, they only regain fat (not muscle), leaving them with a net muscle loss.

In the end, the person is metabolically ‘fatter,’ or sometimes referred to as “skinny fat” – a phenomenon where you have increased visceral fat, but little muscle mass so you are ‘normal’ weight, but metabolically unhealthy.

• Weight rebound

A study in the Journal of Pharmacology and Therapeutics found that a majority of people who take semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) gain most of the weight back within a year of stopping the medication.

Benjamin Bikman, a professor of Cell Biology and Physiology at Brigham Young University and author of Why We Get Sick, says weight rebound can be at least partly explained by the effect that the drugs have on fat cell biology.

“Animal studies have shown that while these drugs can shrink the size of fat cells, it can also increase the number of new fat cells being produced,” explained Bikman. “Having more, but smaller, fat cells is perfectly healthy…until you stop the drug.”

He added, “So once the person stops taking the drug, their cravings come back, and their fat cells will be allowed to grow. But because they have more fat cells now, the person may end up heavier than when they commenced the drug.”

• Bone density

In addition to weight loss, the trials show a small risk of reduced bone density of about 2%, which may sound modest, but it has been associated with a 16% increased risk of hip fracture.

• Suicidal risk

In July, reports of sudden onset thoughts of suicide associated with GLP-1 drugs spurred the European Medicines Agency to announce that it would investigate data on the risk of suicidal thoughts and thoughts of self-harm.

Some have hypothesised that it could be due to the drugs’ impact on the gastrointestinal tract where 95% of serotonin is produced – a neurotransmitter that plays a key role in mood and sleep.

Penny Ward, an expert on EU drug safety monitoring and professor at Kings College in London said the most likely outcome of this investigation will be a change in the drug’s label in the EU to carry a warning of the possible adverse effect of suicidal thoughts.

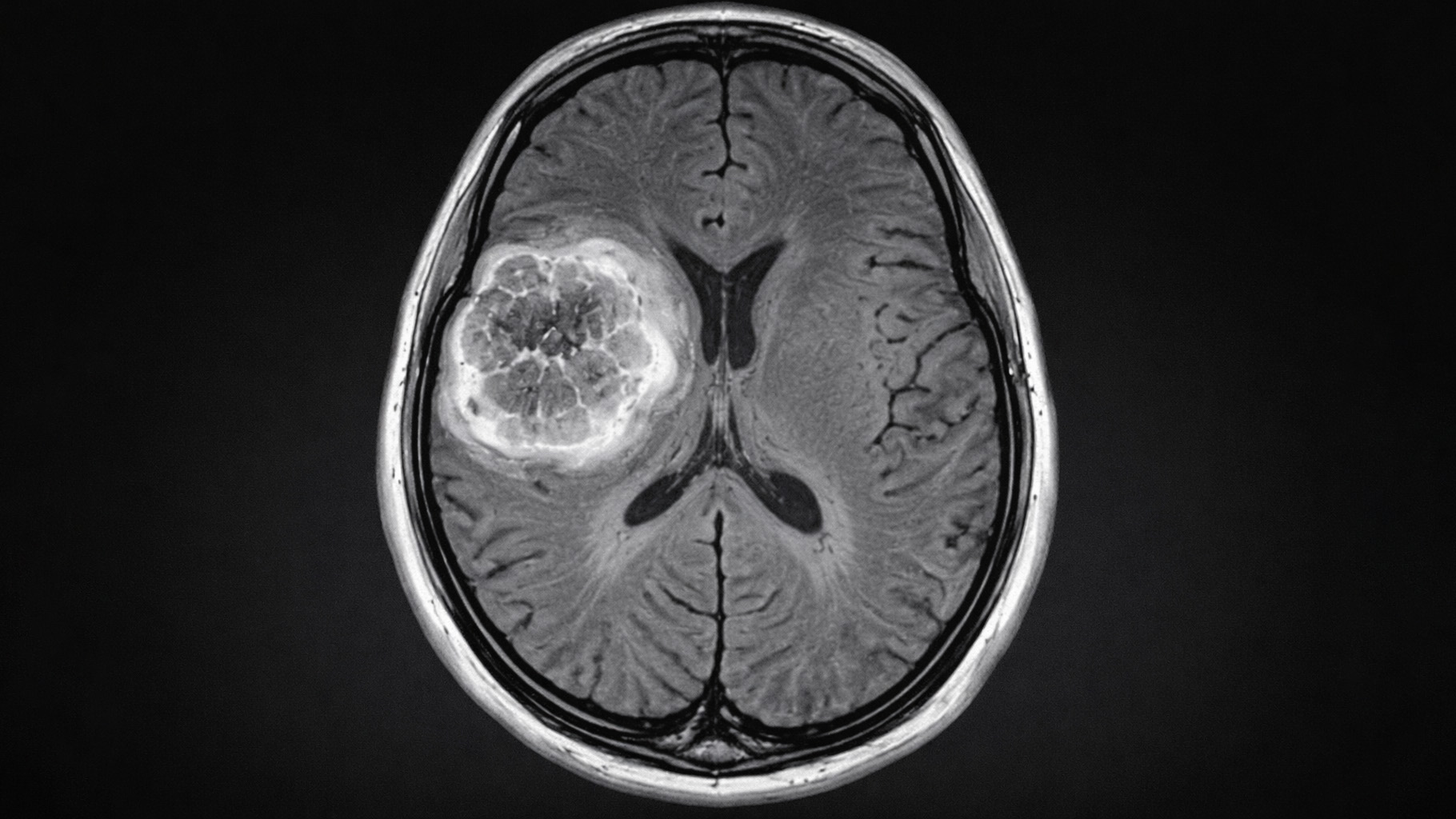

• Cancer risk

Currently, the medication’s label carries a black box warning against prescribing to people with a family history of thyroid tumours and doctors are instructed to counsel patients on thyroid cancer risks.

Read More

Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in rheumatology, who writes for online media and top tiered medical journals. For over a decade, she produced TV documentaries for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and has worked as a speechwriter and political advisor for the South Australian Science Minister. She is a 2023 Brownstone fellow.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

One Comment

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

How a Low-Carb Ketogenic Diet Naturally Activates the Same Pathways

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life

Great article. I have seen people who thought this was a quick fix and have now gained all weight back plus some because they didn’t create any sustainable habits. Education like this is needed on the topic. Please keep up the great work!