Summary

La giornalista medica investigativa Maryanne Demasi analizza i principali problemi legati alla pubblicazione scientifica, compresi problemi con The Broken Science Initiative, Peer Review e pre-stampa, politizzazione delle riviste scientifiche, censura scientifica e diminuzione della fiducia da parte dei lettori. Demasi mette in evidenza gli argomenti di vari critici, come l'ex redattore del British Medical Journal Richard Smith che propone che Peer Review spesso ignora la ricerca rivoluzionaria e fallisce regolarmente nel rilevare frodi. Smith riconosce che le riviste consolidate hanno un'influenza, in particolare per i ricercatori junior che cercano di costruire la loro carriera accademica. Mentre Smith vede ancora un bisogno per le riviste mediche, sostiene metodi di pubblicazione alternativi, come Substack. Alcuni esperti, come John Ioannidis, sono preoccupati per la potenziale frammentazione della letteratura scientifica con l'emergere di questi nuovi modelli di pubblicazione. Ioannidis e sostenitori di un corpo unificato e completo di ricerca. La discussione svela anche preoccupazioni per la fiducia in calo nelle riviste mediche e nella medicina in generale negli ultimi anni, a causa di fattori come la politizzazione della scienza e la censura scientifica durante la pandemia di Covid-19. Ioannidis evidenzia l'eventuale inesattezza di molte scoperte di ricerca pubblicate, la svista frettolosa di molte delle prime ricerche su Covid-19 e la diffusione di informazioni errate e disinformazione. Mentre sia i metodi di pubblicazione tradizionali che quelli autonomi hanno i loro sostenitori e detrattori, la questione centrale ruota attorno al miglioramento della credibilità, integrità e accessibilità della ricerca medica. Andando avanti, la comunità di ricerca scientifica deve valutare come identificare e comunicare al meglio le scoperte scientifiche al pubblico in modo accurato ed efficace.'

'Molti scienziati stanno riflettendo su come la ricerca viene verificata e condivisa con il mondo. In questo articolo, ascoltiamo gli editori di riviste scientifiche, cioè le persone che decidono cosa va inserito nelle riviste di ricerca. Le riviste di ricerca sono un po' come giornali o riviste, ma invece di condividere storie, condividono nuove scoperte. I risultati sono provati con esperimenti, osservazioni e informazioni raccolte. Ascoltiamo anche dai ricercatori, le persone che fanno queste scoperte, che inviano il loro lavoro alle riviste e sperano di essere pubblicati. Quando la ricerca viene pubblicata, viene presa più seriamente. Richard Smith, che una volta ha curato una rivista di punta, sottolinea che i passaggi necessari per la pubblicazione della ricerca non sempre hanno senso. A volte, i verificatori ignorano studi che sono davvero buoni. Altre volte, commettono errori grossolani nella ricerca e questi risultati errati finiscono comunque nelle mani del pubblico. Questo può causare grossi problemi, soprattutto quando i lettori si affidano alle riviste di ricerca per prendere decisioni su cosa mangiano, quali medicine prendono e altre scelte di vita. Alcuni critici delle riviste sono preoccupati per la censura. La censura è quando certe persone o gruppi hanno il controllo su quale conoscenza viene condivisa e ne nascondono deliberatamente una parte - anche se l'informazione è corretta al 100%. Molte volte, ciò avviene perché i censori non sono d'accordo con l'informazione per motivi politici o sociali. Durante la pandemia, abbiamo visto questo accadere con uno studio sui vaccini che è stato ritirato dopo essere stato condiviso. Questo ha fatto chiedere a certe persone se le grandi riviste mediche stessero nascondendo alcuni lavori. Scienziati famosi, come Carl Heneghan e Tom Jefferson, hanno scelto di saltare le grandi riviste e condividere il loro lavoro in riviste meno conosciute e online, perché pensano sia più veloce e facile. Ma, persone come John Ioannidis, un ricercatore, temono che questo potrebbe incasinare come vengono scritti i libri scientifici. Ioannidis ritiene che la ricerca medica dovrebbe rimanere unita in modo che le persone possano vedere il quadro completo, invece di avere ricerche importanti in luoghi che la gente potrebbe non conoscere. Un ex editore di ricerca, tuttavia, sostiene che i ricercatori condividano il loro lavoro perché pensa che il processo di verifica sia troppo lento e spesso impedisca le idee del ricercatore di emergere. Un'altra editor di ricerca è preoccupata che le persone stiano iniziando a perdere fiducia nelle riviste mediche e nei medici e nella medicina in generale. È triste che la scienza, come molti argomenti durante la pandemia, sia diventata politica. Anche Ioannidis parla di persone che perdono fiducia e pensa che molti dei risultati condivisi nella ricerca potrebbero essere sbagliati. Questa conversazione mostra la lotta tra il vecchio modo di controllare gli studi e il nuovo modo in cui chiunque può accedere agli studi. Mentre il vecchio modo è ancora il modo principale per fare bene nel lavoro di uno scienziato, la possibile segretezza e l'occultamento hanno reso le persone infelici. La lotta principale riguarda il rendere la ricerca medica più affidabile e facile da ottenere. Tutti vogliono assicurarsi che tutti gli altri ottengano informazioni scientifiche accurate e utili.'

--------- Original ---------

'Negli ultimi anni, è emerso un nuovo dibattito nella comunità scientifica sul modo in cui la ricerca viene controllata e pubblicata. In questo articolo, i ricercatori e gli editori di riviste scientifiche discutono i principali problemi all'interno della pubblicazione scientifica, inclusi come questi problemi influiscono sia sui singoli scienziati che sul pubblico generale. Richard Smith, ex direttore del British Medical Journal, svela le sue preoccupazioni sulla peer review. Il processo di peer review funge da colonna vertebrale del processo di verifica dei fatti delle riviste scientifiche. Prima di essere pubblicati in una rivista scientifica, gli studi vengono esaminati da altri scienziati. La maggior parte delle volte, i revisori tra pari vengono scelti perché stanno svolgendo una ricerca simile, il che può creare una sorta di pregiudizio, soprattutto in campi in cui ci sono solo poche persone che svolgono quel tipo di lavoro perché rende molto facile sapere come sono i revisori e può portare a un ambiente di tipo ti gratto la schiena se tu gratti la mia. Questo può creare un pregiudizio Smith sostiene che "la peer review è basata sulla fede, non sulla prova" sottolineando che alcuni studi precedentemente respinti dai revisori tra pari diventano successivamente dei pezzi di scienza molto apprezzati. Fa anche notare che gli errori passano regolarmente attraverso la peer review. I critici delle grandi riviste sono preoccupati per la censura. Durante la pandemia, abbiamo visto esempi di questo tipo di dibattito, incluso un articolo sui vaccini mRNA che è stato ritirato dopo la pubblicazione. Questo ha portato alcune persone a chiedersi se le grandi riviste mediche stessero censurando certi lavori. Alcuni scienziati noti, come Carl Heneghan e Tom Jefferson, hanno deciso di saltare le grandi riviste e pubblicare il loro lavoro in riviste più piccole e specializzate e su piattaforme online come Substack, perché pensano che sia più veloce e meno complicato. Ma, altri come il ricercatore John Ioannidis, temono che ciò potrebbe distorcere la letteratura scientifica. Ioannidis pensa che dobbiamo mantenere la ricerca medica unificata ed equilibrata. , Smith sostiene l'autopubblicazione perché trova il processo tradizionale troppo lento e pensa che spesso soffochi la voce dell'autore. Riconosce anche che le grandi riviste detengono molta influenza, soprattutto per i giovani ricercatori che cercano di costruire la loro carriera. L'ex editore di JAMA Internal Medicine, Rita Redberg, è preoccupata per la fiducia in calo nelle riviste mediche e nel campo medico in generale. È sconvolta da come le discussioni scientifiche, come il dibattito sulla maschera durante la pandemia, siano diventate politiche. Ioannidis porta anche alla luce la perdita di fiducia del pubblico, facendo riferimento al suo stesso lavoro che mostra che molti risultati di ricerca pubblicati potrebbero essere falsi. Questa discussione mostra i punti di vista contrastanti tra la pubblicazione tradizionale, revisionata tra pari, e i metodi di accesso aperto più recenti. Mentre il vecchio metodo è ancora il principale indicatore del successo professionale, il potenziale segreto e la censura hanno portato a una crescente insoddisfazione. Piattaforme come Substack offrono più controllo agli autori e un accesso più veloce per i lettori, ma affrontano critiche per aver potenzialmente minato la letteratura scientifica e per aver diviso la scienza. Nel complesso, entrambi i metodi hanno i loro sostenitori e critici, il punto centrale del dibattito riguarda il miglioramento dell'affidabilità e dell'accessibilità della ricerca medica. Tutti vogliono assicurarsi che il pubblico ottenga informazioni scientifiche accurate ed efficaci.'

--------- Original ---------

Former editor of The BMJ says, “It’s interesting to me in a way that journals are still alive, because I think there’s a lot of reasons why they should be dead.”

Problems that have plagued medical journals for decades include the failure of peer review, replication crisis, ghost-writing, and the influence of Big Pharma.

In 2004, Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet wrote, “Journals have devolved into information laundering operations for the pharmaceutical industry.”

More recently, Peter Gøtzsche, one of the founding fathers of the Cochrane Collaboration said, “The medical publishing system is broken. It doesn’t ensure that solid research which goes against financial interests can get published without any major obstacles.”

Scientific publishing is now one of the most profitable businesses. Elsevier, for example, made $2.9 billion in annual revenue with a profit margin approaching 40%, rivalling that of Apple and Google.

But despite these impressive numbers, trust in medical journals has diminished, and this has only been exacerbated by the covid-19 pandemic.

Peer review fail

Former editor of The BMJ Richard Smith once famously wrote; “Peer review is faith not evidence based, but most scientists believe in it as some people believe in the Loch Ness monster.”

In a recent conversation with Richard Smith, he explained why.

“Peer review was thought to be at the heart of science – that is, who gets a grant or who gets a Nobel Prize – and I suppose it wasn’t until the 80s and 90s that somebody actually examined it – it was just sort of assumed to be a good thing,” said Smith.

“Then people began a series of experiments – there was a Cochrane review – looking at the evidence to see if peer-review was beneficial. And actually, what they found was that there was really no evidence,” he said.

Smith, who worked at The BMJ for 25 years said the peer-review process is slow, it’s expensive, and it stifles the publication of innovative ideas.

“There are lots of examples of ground-breaking work that were rejected by peer-reviewers but go on to win Nobel Prizes. Is the work crazy? Or is it truly genius? Peer review is not good at deciding that,” he said.

Peer review also fails to detect fraud. The recent Surgisphere scandal is a case in point.

Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine were forced to retract studies after researchers reported a link between treatment with hydroxychloroquine and increased death of hospitalised covid patients.

Glaring discrepancies were found in the database underpinning the studies, but were not detected in the peer-review process.

“If researchers say there were 200 patients in the study, then you assume there were. But we have increasing evidence that that’s not the case – there are a lot of zombie trials that never happened or have been manipulated in some way,” said Smith.

“So, in a nutshell, we have lots and lots of evidence of the downside of peer review and really no convincing evidence of its upside,” he added.

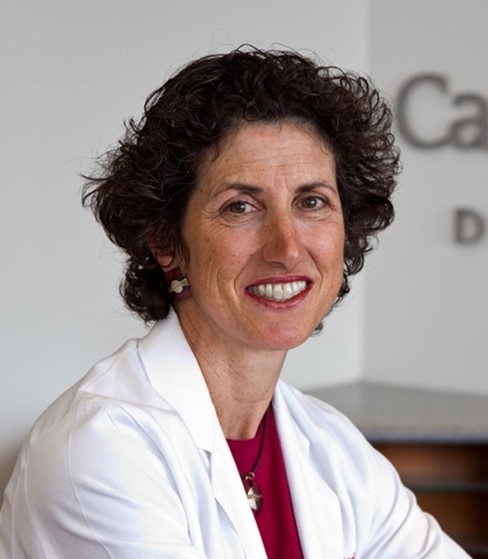

Rita Redberg, a cardiologist at the University of California San Francisco, who recently stepped down after 14 years as chief editor of JAMA Internal Medicine, concedes that peer-review is “not perfect”.

“You always assume that what the authors are telling you is true. The process depends on the honesty of the authors, and yes, people can be dishonest. But we’re doctors, we’re not investigators with the resources of the FBI. Of course, when any potential dishonesty comes to our attention, we will investigate,” said Redberg.

“It has its problems, but what’s the alternative? No peer-review? In general, I think peer review is much better than a system without peer review,” added Redberg.

Politicisation of journals

During the pandemic, some journal editors became increasingly politicised.

Editors at the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, took the rare step of writing an editorial in 2020, urging American voters to oust the sitting President. It was a controversial move.

John Ioannidis, Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, and the most cited scientist in the world, said he is not in favour of the politicisation of medical journals.

“The message it sends is that scientific journals are just another arm of the political propaganda machine,” said Ioannidis.

“That’s not to say that scientific journals shouldn’t take stances on important issues that are decided by politicians like climate change, regulation of industry, and environmental pollution. I just think the editorials were very poor choices and not for the pages of the journals,” he said.

Ioannidis is not convinced that these political statements swayed anyone to cross the political aisle, and thinks the editorials should be retracted.

“To be honest, the editors who made these statements should retract their own editorials on these political issues. Editors can keep their political orientation and still cover all the big important medical issues,” he added.

Emergence of pre-prints

Pre-prints are non-peer-reviewed articles posted on servers such as medRxiv and bioRxiv, that allow thousands of people to view the research. Many see this as a double-edged sword.

It enables faster data sharing in an emergency and quick feedback, but it also opens the door to sloppy science that can be widely disseminated by the public and the media.

Redberg’s personal view is that pre-prints, which have not undergone peer-review, are potentially harmful.

“I think there’s a danger of putting out information that’s not accurate. For approval of drugs and devices, it’s worth taking the time to get things right. I feel much more confident that you’re going to get it right if it’s undergone peer review,” said Redberg.

“I think it started with very good intentions – people sharing their work and getting comments – but the articles stay up there even after they’re published in journals, and having an older, different–and possibly inaccurate–version remaining in the public sphere may inadvertently disseminate incorrect information,” added Redberg.

Ioannidis, on the other hand, says he is in favour of pre-prints because “they offer more transparency in the system, and they allow for some earlier dissemination of work,”.

But he warned it can be a battlefield citing experiences where some of his pre-prints would receive more than 1000 peer reviews within a day of release.

“A few were very, very helpful. Hundreds of them were just abuse. It was a very traumatic experience. If you separate what is the good contribution versus the abuse, then I think that they’re useful,” said Ioannidis.

Smith argues that pre-prints actually prove his point about the failure of peer-review. “If you look at what eventually appears in journals, it’s usually very similar to the original pre-print. So, it’s evidence that peer review has not made much of a difference,” said Smith.

“What I argue is that the peer review should not be three or four selected people looking at something before it’s published, but where the ideas are available to everybody. That’s the real peer review,” he said.

Scientific censorship

Publishing articles in medical journals during the pandemic, especially research that was critical of vaccine safety, was sometimes censored or retracted for no good reason.

For example, a peer-reviewed paper linking the mRNA vaccines with myocarditis, authored by doctors Jessica Rose and Peter McCullough, was suddenly withdrawn with insufficient cause.

Some high-profile scientists have decided that the time burden and logistical intensity of publishing in the major medical journals is simply not worth it.

Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson, for example, two of the most reputable researchers in the world, say they’ll only publish in specialised journals that have peer-reviewers with the right expertise.

Otherwise, the bulk of their work is published on the writing platform, Substack (Trust The Evidence).

“I do worry about that,” says Ioannidis. “We need the voices of people like Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson and others in the mix. I suppose if they’ve been thwarted, then there must be some venue where that missing part can appear, and perhaps Substack caters to that need.”

“I do wish that we get them back into the traditional type of medical journals though. If the classical literature is missing a very key perspective like theirs, then the distortion becomes bigger,” he said.

“It makes it more difficult to balance the literature when knowledgeable, critical voices are missing. I know I may sound like I’m willing to stick to that sinking ship. But I would prefer to not fragment science into medical journals, and Substack and who knows where else,” added Ioannidis.

Smith on the other hand, is more enthusiastic about self-publishing.

“I’m in favour of getting it out there. Let the world decide. It makes a lot of sense to me,” says Smith citing his own challenges with publishing in medical journals.

“Recently, I submitted a piece to the Lancet – a book review – and there was the hassle of all the forms you have to fill in, all the comments from the editors, which I mean – maybe it’s arrogance on my part – but didn’t seem to make things much better,” said Smith in a perturbed tone.

“You’ve got a particular voice, and they disrupt it to some extent. So, it ends up much messier. Doesn’t feel to me like there’s a lot of value added in that process,” he said.

Smith says self-publishing is more of a problem if you are a junior researcher and want to rise in the academic arena.

“You need to publish in these journals because that’s how you’re judged. If you’ve published in the New England Journal of Medicine, it’s assumed to be a very significant piece of research. I mean, it’s completely unscientific to use the place you publish as a surrogate for the value of the research, but that’s what continues to happen,” said Smith.

Diminished trust

Redberg says it’s not just medical journals that lost trust.

“I think people’s trust in medicine and public health diminished in general in the last few years. The sad part to me is that science became political – whether you wore a mask or not became a political statement – It’s not a political question. It’s a scientific question,” said Redberg.

Ioannidis who famously authored the paper, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” said, “I think that we are losing…well, we have already lost the trust of a major part of the population.”

“Covid created a lot of extra stress on the system. People wanted to publish papers very quickly, by now it’s almost a million papers. We’ve looked at the covid literature and most of it was very sloppy, corners were cut, probably worse than usual,” said Ioannidis.

“The frontier of science is broken at the moment. If we do not acknowledge that we have a problem – and make no mistake – we have a very serious problem, then it will be difficult to defend against conspiracy theories or against people who just want to make money by spreading misinformation or disinformation,” he added.

So, are medical journals dead?

“I don’t think medical journals are dead, no. I feel like they’re busier and more important than ever, because there’s so much innovation and I think that disseminating it through a high-quality, peer-review process is the best way to go,” said Redberg.

Ioannidis is quick to acknowledge there is a problem with medical journals. “They are very sick, and they suffer from all sorts of diseases, but I just don’t want to say that I’m giving up on them. They need to transform. I hope that they get better. But I don’t want to proclaim them dead yet.”

Smith agrees that there’s a role for medical journals, but he seems less invested.

“It’s interesting to me in a way that journals are still alive, because I think there’s a lot of reasons why they should be dead,” said Smith.

Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in rheumatology, who writes for online media and top tiered medical journals. For over a decade, she produced TV documentaries for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and has worked as a speechwriter and political advisor for the South Australian Science Minister. She is a 2023 Brownstone fellow.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

What Addiction Medicine Missed – and What Bitten Jonsson’s Work Reveals

The Daley Fix with Matt Shindeldecker & Debbie Wagner

Obviously a massive problem that science has become a business…

The idea of peer review has good intentions, but it is only as good as the reviewer is honest and has the resources to sift through the bullshit.

Ultimately, I think, the solution starts with education and a culture change. That is why the Broken Science Initiative is so powerful. If those who lead the way have a deeper understanding of what science is, and really care about the Truth, the process fixes itself.

Like Greg says – Any man, but not every man, will learn this.

…My hope is that enough learn to hold a dim light at the end of the dark mainstream tunnel.

Thank you for the article Maryanne. One important thing to mention regarding journals is the paywall that keeps researchers away from information. Science isn’t being shared openly. Perhaps, the model could quickly fall apart with a peer reviewed “wiki-medical journal”.