Summary

'La periodista de investigación médica Maryanne Demasi expone los principales problemas en la publicación científica, incluyendo problemas con la Peer Review y los pre-prints, la politización de las revistas científicas, la censura científica, y la disminución de la confianza de los lectores. Demasi resalta argumentos de varios críticos, como el ex editor de British Medical Journal, Richard Smith, quien propone que la Peer Review a menudo pasa por alto la investigación innovadora y regularmente no detecta el fraude. Smith reconoce que las revistas establecidas tienen influencia, particularmente para los investigadores junior que buscan construir sus carreras académicas. Aunque Smith todavía ve la necesidad de revistas médicas, aboga por métodos de publicación alternativos, como Substack. Algunos expertos, como John Ioannidis, están preocupados por la posible fragmentación de la literatura científica con estos nuevos modelos de publicación emergentes. Ioannidis y defensores de un cuerpo unificado y completo de investigación. . La discusión también descubre preocupaciones sobre la disminución de la confianza en las revistas médicas y en la medicina en general durante los últimos años, debido a factores como la politización de la ciencia y la censura científica durante la pandemia de Covid-19. Ioannidis menciona la posible inexactitud de muchos hallazgos de investigación publicados, la negligencia apresurada de gran parte de la investigación temprana de Covid-19, y la difusión de información errónea y desinformación. Tanto los métodos de auto-publicación como los tradicionales tienen sus defensores y detractores, la cuestión central gira en torno a mejorar la credibilidad, integridad y accesibilidad de la investigación médica. Avanzando, la comunidad de investigación científica necesita evaluar cómo identificar y comunicar de la mejor manera los hallazgos científicos al público de una manera precisa y efectiva.'

'Muchos científicos están pensando en cómo se verifica la investigación y se comparte con el mundo. En este artículo, escuchamos a los editores de revistas científicas, también conocidos como las personas que deciden qué va a las revistas de investigación. Las revistas de investigación son algo así como periódicos o revistas, pero en lugar de compartir historias, comparten nuevos descubrimientos. Los hallazgos se prueban con experimentos, observaciones e información recopilada. También escuchamos a los investigadores, las personas que hacen estos descubrimientos, quienes envían su trabajo a las revistas y esperan que se publiquen. Cuando la investigación se publica, se toma más en serio. Richard Smith, quien solía ser editor de una revista de alto rango, señala que los pasos requeridos para que una investigación se publique no siempre tienen sentido. A veces, los verificadores de hechos pasan por alto estudios que son realmente buenos. Otras veces, se pierden errores importantes en la investigación y esos hallazgos incorrectos todavía llegan a manos del público. Eso puede causar problemas importantes, especialmente cuando los lectores confían en las revistas de investigación para tomar decisiones sobre qué alimentos comen, qué medicamentos toman y otras elecciones de estilo de vida. Algunos críticos de las revistas están preocupados por la censura. La censura es cuando ciertas personas o grupos tienen control sobre qué conocimiento se comparte y deliberadamente mantienen algo oculto, incluso si la información es 100% correcta. Muchas veces, esto se debe a que los censores no están de acuerdo con la información por razones políticas o sociales. Durante la pandemia, vimos que esto ocurrió con un estudio sobre vacunas que fue retirado después de haberse compartido. Esto hizo que algunas personas preguntaran si las grandes revistas médicas estaban ocultando cierto trabajo. Científicos famosos, como Carl Heneghan y Tom Jefferson, optaron por saltarse las grandes revistas y compartir su trabajo en revistas menos conocidas y en línea, porque creen que es más rápido y fácil. Pero, personas como John Ioannidis, un investigador, están preocupadas de que esto pueda confundir la forma en que se escriben los libros científicos. Ioannidis cree que la investigación médica debería mantenerse unida para que las personas puedan ver el cuadro completo, en lugar de tener una investigación importante en lugares que las personas pueden no conocer. Sin embargo, un ex editor de investigación respalda a los investigadores que comparten su propio trabajo porque cree que el proceso de verificación es demasiado lento y a menudo impide que las ideas del investigador se den a conocer. Otra editora de investigación está preocupada de que las personas están comenzando a perder la confianza en las revistas médicas y en los médicos y la medicina en general. Le entristece que la ciencia, como muchos argumentos durante la pandemia, se haya politizado. Ioannidis también habla de la pérdida de confianza y piensa que muchos de los resultados compartidos en la investigación podrían estar equivocados. Esta conversación muestra la lucha entre la antigua forma de verificar los estudios y la nueva forma en que cualquiera puede acceder a los estudios. Mientras que la antigua forma sigue siendo la principal forma de tener éxito en el trabajo de un científico, el posible secreto y ocultación ha hecho que las personas se sientan infelices. La pelea principal es acerca de hacer la investigación médica más confiable y fácil de obtener. Todos quieren asegurarse de que todos los demás obtengan información científica precisa y útil.'

--------- Original ---------

'En los últimos años, ha surgido un nuevo debate en la comunidad científica sobre la forma en que se verifica y publica la investigación. En este artículo, los investigadores y los editores de revistas de ciencia discuten los principales problemas dentro de la publicación científica, incluyendo cómo estos problemas impactan tanto a los científicos individuales como al público general. Richard Smith, el ex editor del British Medical Journal, expone sus preocupaciones con el Peer Review. El proceso de Peer Review sirve como columna vertebral del proceso de verificación de hechos de las revistas de ciencia. Antes de ser publicados en una revista de ciencia, los estudios son revisados por otros científicos. La mayoría de las veces, los revisores son seleccionados porque están haciendo una investigación similar, lo cual puede crear un tipo de sesgo especialmente en campos donde hay pocas personas haciendo ese tipo de trabajo porque facilita saber cómo son los revisores y puede llevar a un ambiente de tú me rascas la espalda, yo te rasco la tuya. . Esto puede crear un sesgo. Smith argumenta que “la Peer Review es fe no basada en evidencia” señalando que algunos estudios previamente rechazados por los revisores pasan a ser piezas de ciencia altamente valoradas. También hace hincapié en que los errores regularmente pasan por la Peer Review. Los críticos de las grandes revistas están preocupados por la censura. Durante la pandemia, vimos ejemplos de este tipo de debate, incluyendo un artículo sobre las vacunas de ARNm que fue retirado después de ser publicado. Esto hizo que algunas personas se preguntaran si las grandes revistas médicas estaban censurando cierto trabajo. Algunos científicos conocidos, como Carl Heneghan y Tom Jefferson, decidieron saltarse las grandes revistas y publicar su trabajo en revistas más pequeñas, especializadas y plataformas en línea como Substack, porque piensan que es más rápido y menos complicado. Pero, otros como el investigador John Ioannidis, temen que esto pueda distorsionar la literatura científica. Ioannidis piensa que necesitamos mantener la investigación médica unificada y equilibrada. , Smith apoya la auto-publicación porque encuentra el proceso tradicional demasiado lento y cree que a menudo sofoca la voz del autor. También reconoce que las grandes revistas tienen mucha influencia, especialmente para los jóvenes investigadores que buscan construir sus carreras. La ex editora de JAMA Internal Medicine, Rita Redberg, está preocupada por la decreciente confianza en las revistas médicas y en el campo médico en general. Está molesta con cómo las discusiones científicas, como el debate de la máscara durante la pandemia, se han politizado. Ioannidis también menciona la pérdida de confianza del público, señalando su propio trabajo que muestra que muchos hallazgos de investigaciones publicadas pueden ser falsos. Esta discusión muestra las opiniones conflictivas en torno a la publicación tradicional, revisada por pares, y los métodos más nuevos y de acceso abierto. Aunque el antiguo método sigue siendo el principal indicador de éxito profesional, el potencial secreto y la censura ha llevado a una creciente insatisfacción. Plataformas como Substack ofrecen más control para los autores y un acceso más rápido para los lectores, pero enfrentan críticas por posiblemente socavar la literatura científica y fragmentar la ciencia. En general, ambos métodos tienen sus partidarios y críticos, el punto central del debate es sobre mejorar la confiabilidad y la accesibilidad de la investigación médica. Todos quieren asegurarse de que el público obtenga información científica precisa y efectiva.'

--------- Original ---------

Former editor of The BMJ says, “It’s interesting to me in a way that journals are still alive, because I think there’s a lot of reasons why they should be dead.”

Problems that have plagued medical journals for decades include the failure of peer review, replication crisis, ghost-writing, and the influence of Big Pharma.

In 2004, Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet wrote, “Journals have devolved into information laundering operations for the pharmaceutical industry.”

More recently, Peter Gøtzsche, one of the founding fathers of the Cochrane Collaboration said, “The medical publishing system is broken. It doesn’t ensure that solid research which goes against financial interests can get published without any major obstacles.”

Scientific publishing is now one of the most profitable businesses. Elsevier, for example, made $2.9 billion in annual revenue with a profit margin approaching 40%, rivalling that of Apple and Google.

But despite these impressive numbers, trust in medical journals has diminished, and this has only been exacerbated by the covid-19 pandemic.

Peer review fail

Former editor of The BMJ Richard Smith once famously wrote; “Peer review is faith not evidence based, but most scientists believe in it as some people believe in the Loch Ness monster.”

In a recent conversation with Richard Smith, he explained why.

“Peer review was thought to be at the heart of science – that is, who gets a grant or who gets a Nobel Prize – and I suppose it wasn’t until the 80s and 90s that somebody actually examined it – it was just sort of assumed to be a good thing,” said Smith.

“Then people began a series of experiments – there was a Cochrane review – looking at the evidence to see if peer-review was beneficial. And actually, what they found was that there was really no evidence,” he said.

Smith, who worked at The BMJ for 25 years said the peer-review process is slow, it’s expensive, and it stifles the publication of innovative ideas.

“There are lots of examples of ground-breaking work that were rejected by peer-reviewers but go on to win Nobel Prizes. Is the work crazy? Or is it truly genius? Peer review is not good at deciding that,” he said.

Peer review also fails to detect fraud. The recent Surgisphere scandal is a case in point.

Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine were forced to retract studies after researchers reported a link between treatment with hydroxychloroquine and increased death of hospitalised covid patients.

Glaring discrepancies were found in the database underpinning the studies, but were not detected in the peer-review process.

“If researchers say there were 200 patients in the study, then you assume there were. But we have increasing evidence that that’s not the case – there are a lot of zombie trials that never happened or have been manipulated in some way,” said Smith.

“So, in a nutshell, we have lots and lots of evidence of the downside of peer review and really no convincing evidence of its upside,” he added.

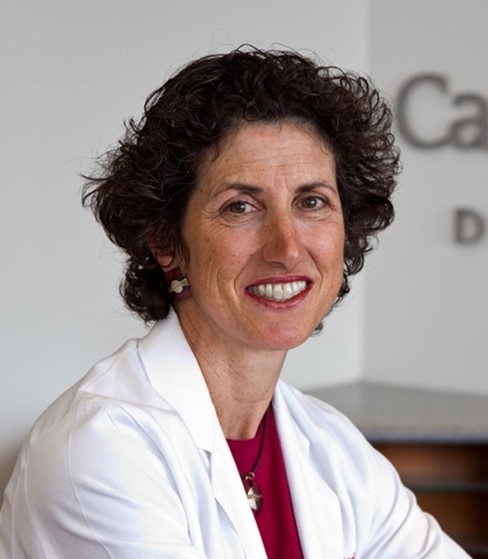

Rita Redberg, a cardiologist at the University of California San Francisco, who recently stepped down after 14 years as chief editor of JAMA Internal Medicine, concedes that peer-review is “not perfect”.

“You always assume that what the authors are telling you is true. The process depends on the honesty of the authors, and yes, people can be dishonest. But we’re doctors, we’re not investigators with the resources of the FBI. Of course, when any potential dishonesty comes to our attention, we will investigate,” said Redberg.

“It has its problems, but what’s the alternative? No peer-review? In general, I think peer review is much better than a system without peer review,” added Redberg.

Politicisation of journals

During the pandemic, some journal editors became increasingly politicised.

Editors at the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, took the rare step of writing an editorial in 2020, urging American voters to oust the sitting President. It was a controversial move.

John Ioannidis, Professor of Medicine at Stanford University, and the most cited scientist in the world, said he is not in favour of the politicisation of medical journals.

“The message it sends is that scientific journals are just another arm of the political propaganda machine,” said Ioannidis.

“That’s not to say that scientific journals shouldn’t take stances on important issues that are decided by politicians like climate change, regulation of industry, and environmental pollution. I just think the editorials were very poor choices and not for the pages of the journals,” he said.

Ioannidis is not convinced that these political statements swayed anyone to cross the political aisle, and thinks the editorials should be retracted.

“To be honest, the editors who made these statements should retract their own editorials on these political issues. Editors can keep their political orientation and still cover all the big important medical issues,” he added.

Emergence of pre-prints

Pre-prints are non-peer-reviewed articles posted on servers such as medRxiv and bioRxiv, that allow thousands of people to view the research. Many see this as a double-edged sword.

It enables faster data sharing in an emergency and quick feedback, but it also opens the door to sloppy science that can be widely disseminated by the public and the media.

Redberg’s personal view is that pre-prints, which have not undergone peer-review, are potentially harmful.

“I think there’s a danger of putting out information that’s not accurate. For approval of drugs and devices, it’s worth taking the time to get things right. I feel much more confident that you’re going to get it right if it’s undergone peer review,” said Redberg.

“I think it started with very good intentions – people sharing their work and getting comments – but the articles stay up there even after they’re published in journals, and having an older, different–and possibly inaccurate–version remaining in the public sphere may inadvertently disseminate incorrect information,” added Redberg.

Ioannidis, on the other hand, says he is in favour of pre-prints because “they offer more transparency in the system, and they allow for some earlier dissemination of work,”.

But he warned it can be a battlefield citing experiences where some of his pre-prints would receive more than 1000 peer reviews within a day of release.

“A few were very, very helpful. Hundreds of them were just abuse. It was a very traumatic experience. If you separate what is the good contribution versus the abuse, then I think that they’re useful,” said Ioannidis.

Smith argues that pre-prints actually prove his point about the failure of peer-review. “If you look at what eventually appears in journals, it’s usually very similar to the original pre-print. So, it’s evidence that peer review has not made much of a difference,” said Smith.

“What I argue is that the peer review should not be three or four selected people looking at something before it’s published, but where the ideas are available to everybody. That’s the real peer review,” he said.

Scientific censorship

Publishing articles in medical journals during the pandemic, especially research that was critical of vaccine safety, was sometimes censored or retracted for no good reason.

For example, a peer-reviewed paper linking the mRNA vaccines with myocarditis, authored by doctors Jessica Rose and Peter McCullough, was suddenly withdrawn with insufficient cause.

Some high-profile scientists have decided that the time burden and logistical intensity of publishing in the major medical journals is simply not worth it.

Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson, for example, two of the most reputable researchers in the world, say they’ll only publish in specialised journals that have peer-reviewers with the right expertise.

Otherwise, the bulk of their work is published on the writing platform, Substack (Trust The Evidence).

“I do worry about that,” says Ioannidis. “We need the voices of people like Carl Heneghan and Tom Jefferson and others in the mix. I suppose if they’ve been thwarted, then there must be some venue where that missing part can appear, and perhaps Substack caters to that need.”

“I do wish that we get them back into the traditional type of medical journals though. If the classical literature is missing a very key perspective like theirs, then the distortion becomes bigger,” he said.

“It makes it more difficult to balance the literature when knowledgeable, critical voices are missing. I know I may sound like I’m willing to stick to that sinking ship. But I would prefer to not fragment science into medical journals, and Substack and who knows where else,” added Ioannidis.

Smith on the other hand, is more enthusiastic about self-publishing.

“I’m in favour of getting it out there. Let the world decide. It makes a lot of sense to me,” says Smith citing his own challenges with publishing in medical journals.

“Recently, I submitted a piece to the Lancet – a book review – and there was the hassle of all the forms you have to fill in, all the comments from the editors, which I mean – maybe it’s arrogance on my part – but didn’t seem to make things much better,” said Smith in a perturbed tone.

“You’ve got a particular voice, and they disrupt it to some extent. So, it ends up much messier. Doesn’t feel to me like there’s a lot of value added in that process,” he said.

Smith says self-publishing is more of a problem if you are a junior researcher and want to rise in the academic arena.

“You need to publish in these journals because that’s how you’re judged. If you’ve published in the New England Journal of Medicine, it’s assumed to be a very significant piece of research. I mean, it’s completely unscientific to use the place you publish as a surrogate for the value of the research, but that’s what continues to happen,” said Smith.

Diminished trust

Redberg says it’s not just medical journals that lost trust.

“I think people’s trust in medicine and public health diminished in general in the last few years. The sad part to me is that science became political – whether you wore a mask or not became a political statement – It’s not a political question. It’s a scientific question,” said Redberg.

Ioannidis who famously authored the paper, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” said, “I think that we are losing…well, we have already lost the trust of a major part of the population.”

“Covid created a lot of extra stress on the system. People wanted to publish papers very quickly, by now it’s almost a million papers. We’ve looked at the covid literature and most of it was very sloppy, corners were cut, probably worse than usual,” said Ioannidis.

“The frontier of science is broken at the moment. If we do not acknowledge that we have a problem – and make no mistake – we have a very serious problem, then it will be difficult to defend against conspiracy theories or against people who just want to make money by spreading misinformation or disinformation,” he added.

So, are medical journals dead?

“I don’t think medical journals are dead, no. I feel like they’re busier and more important than ever, because there’s so much innovation and I think that disseminating it through a high-quality, peer-review process is the best way to go,” said Redberg.

Ioannidis is quick to acknowledge there is a problem with medical journals. “They are very sick, and they suffer from all sorts of diseases, but I just don’t want to say that I’m giving up on them. They need to transform. I hope that they get better. But I don’t want to proclaim them dead yet.”

Smith agrees that there’s a role for medical journals, but he seems less invested.

“It’s interesting to me in a way that journals are still alive, because I think there’s a lot of reasons why they should be dead,” said Smith.

Maryanne Demasi is an investigative medical reporter with a PhD in rheumatology, who writes for online media and top tiered medical journals. For over a decade, she produced TV documentaries for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and has worked as a speechwriter and political advisor for the South Australian Science Minister. She is a 2023 Brownstone fellow.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

2 Comments

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

recent posts

The Daley Fix with Matt Shindeldecker & Debbie Wagner

How long-term low-carb adaptation can raise fasting glucose without signaling disease

The Daley Fix with Sherb

Obviously a massive problem that science has become a business…

The idea of peer review has good intentions, but it is only as good as the reviewer is honest and has the resources to sift through the bullshit.

Ultimately, I think, the solution starts with education and a culture change. That is why the Broken Science Initiative is so powerful. If those who lead the way have a deeper understanding of what science is, and really care about the Truth, the process fixes itself.

Like Greg says – Any man, but not every man, will learn this.

…My hope is that enough learn to hold a dim light at the end of the dark mainstream tunnel.

Thank you for the article Maryanne. One important thing to mention regarding journals is the paywall that keeps researchers away from information. Science isn’t being shared openly. Perhaps, the model could quickly fall apart with a peer reviewed “wiki-medical journal”.