In this next video, BSI’s Emily Kaplan explains all-cause mortality, and how it should be included when considering any medical treatment.

TRANSCRIPT

Hi, it’s Emily from the Broken Science Initiative, and I’m going to talk about all cause mortality and why I think it’s essential to know and essential to help you navigating your own health care management. So when we go to seek medical advice, we’re usually focused on a very specific disease or health issue, something that’s brought us into the doctor that we want to cure or treat or get rid of.

And, you know, There’s another really important factor to consider when you’re thinking about intervention, and it’s all cause mortality. So all cause mortality refers to the total number of deaths in a population from any cause over a specific period of time. And in a medical trial, this becomes a really key piece of data to know.

So why do I think it’s perhaps the most important piece of information to get when you’re seeking medical advice? Um, or considering a treatment or any kind of intervention or knowing what your options are. Well, it’s because it’s the most important risk reward calculation that you’re going to make. And I think that it should be asked in regards to everything like Every medicine that you’re prescribed, every intervention you’re thinking about getting, every surgery, every treatment.

So medicines become so specialized that doctors are really focused on the problem that’s presented in front of them, right? The issues that brought you to them. And they’re looking at this through their own specialties. So it can be really easy for them to overlook long term, unintended consequences of their recommendations or how these interventions might combine with other interventions that you’re going to need, you know, down the road.

So it really behooves you as a patient to get to know all cause mortality, get really comfortable with it and ask about it a lot. Here’s what I mean. Okay. So let’s imagine that there’s a drug called BoneRevive. And it was designed to increase bone density, to reduce the risk of fractures, to help with osteoporosis in patients.

The early results showed that it was pretty remarkable at accomplishing that targeted goal. However, like any medication or treatment, it’s never solely about the targeted effect. You have to look at the entire picture. And all cause mortality is the term that basically encapsulates the deaths from any cause in a specific group over a set of time and with our BoneRevive drug, while it was proven very effective in treating osteoporosis, the all cause mortality rates in the treatment group were higher than in the non treatment group or the placebo group.

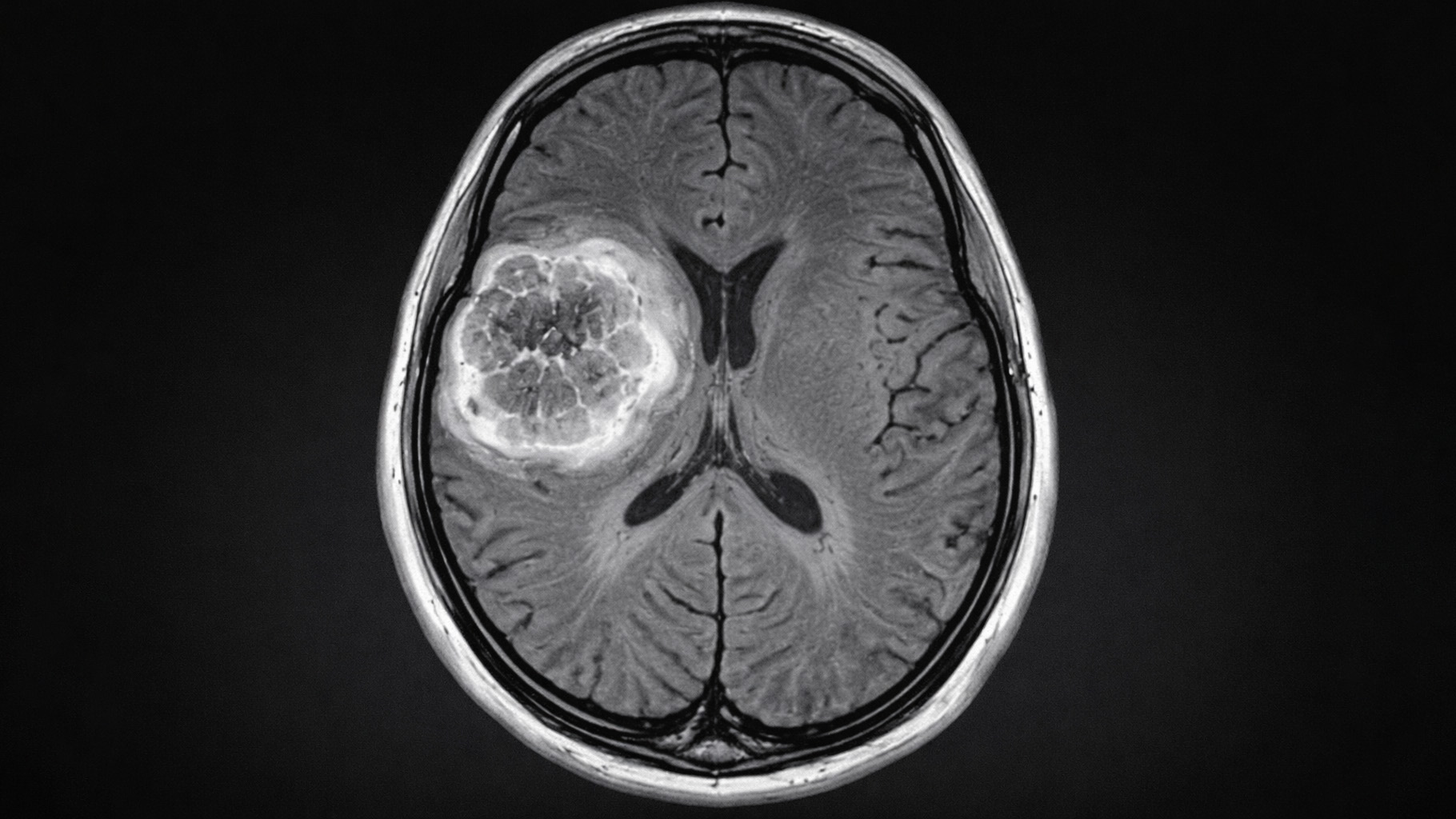

So I hate to say this, but the truth is this is not uncommon in the world of medicine. So for instance, There are cancer treatments that are very effective at shrinking tumors, but they also come with side effects that increase your risk of death from other causes. Same is true for a lot of heart medication.

So there’s heart medication that’s really great for treating the intended heart condition, but poses risks to all of your other vital organs. So it’s the delicate balance and medications and interventions, while designed to treat specific ailments, always carry the potential for unintended consequences.

Right? And we see this in all the side effects. It’s why the medical community, though, leans heavily on this concept of all cause mortality, because that’s a really important end point to be tracking.

So if someone is considering a treatment that carries a certain risk of death, it’s important to weigh that against the all cause mortality rate. If the all cause mortality rate is high, The additional risk from the treatment may be considered perfectly acceptable and actually your best option.

Conversely, if the all cause mortality rate is really low, even a small increase in risk from the treatment may be considered significant. So a real life example of this might be If you’re considering having some sort of cardiovascular surgery, um, and let’s say something that’s pretty risky. So like a heart bypass surgery.

So this procedure carries a certain mortality risk. Now if the patient is already a high likelihood of death due to severe heart disease, which is You know, potentially why you’d have that surgery, then the additional risk of the surgery might be fine. It’s, you know, your other option isn’t so great. The potential benefits of having that surgery might extend your lifespan, improve your quality of life.

All of that can justify the risks of the surgery. Now, on the other hand, if we consider somebody who’s young and healthy with, say, like a minor heart defect, then all cause mortality rate for that person is pretty low. Because they’re young and generally healthy so in that case any kind of small increase that from what would be considered like an elective procedure might be considered very significant.

The all cause mortality is, you know, often used as a clinical endpoint, but it’s also really important for you to remember like where you are in your life and what your quality of life is about and how these interventions may or may not impact those things. Considering all cause mortality with somebody who’s elderly is very different than considering it with somebody who’s young. And these sort of inverse things that I was explaining are both like, you’re looking at the population or the individual. You’re young, you’re healthy. You don’t have your all cause mortality rate is very low, but then this is also applied to treatment groups and placebo groups.

It’s the same concept applied in both. And I’m delineating because you need to make these calculations both based on who you are and what your all cause mortality is, along with all of the other things having to do with quality of life, as well as looking at the research to determine: what is the all cause mortality rate in the treatment group versus the placebo group?

It’s the same calculation. You need to do it twice by looking at the research and finding that data as well as applying it to yourself because the research may not be on people like you. So one of the examples that I like to give, which isn’t necessarily directly all cause mortality, but it’s the same calculation kind of calculating process is women who are put on statins are far more likely to develop type two diabetes than men. Men are primarily studied in clinical trials so there’s a lot of information about women that doctors don’t know about. It’s definitely not, you know, talked about as much as it probably should, how different our bodies are. So if you go to the doctor and the doctor says, hey, Emily, your cholesterol is really high, you know, this makes me a little nervous about your cardiovascular health, which is a whole host of bad science that Malcolm Kendrick does a great job talking about.

But for the sake of this, Okay. Let’s just say that that’s true. So he now thinks that I have a higher increase of having a cardiovascular event because my cholesterol is high, but I’m pre diabetic. So he should be actually calculating, okay, if I put her on a statin, she’s more likely to get type two diabetes.

What’s a greater risk for her? A cardiovascular event based on high cholesterol or type 2 diabetes. That’s the calculation that the doctor should be making. The doctor may not know all of that, but it’s up to you as the patient to sort of know what are the risk factors you’re bringing to the table. And that includes your family history, right?

It includes a lot of stuff. So what are risks that you are bringing to the table? And then what are the risks that are involved with these interventions and how do these things go together?

All cause mortality is often used as an endpoint. in clinical trials, and it’s because it’s great at determining the efficacy.

All cause mortality is often used as the, as an endpoint in clinical trials, and it’s effective at determining whether the intervention worked or not, right? And what the risks were. A reduction in all cause mortality is considered the most robust evidence of a beneficial intervention. Understanding the all cause mortality rate should provide you with some context that allows you for interpreting sort of the significance of the specific causes of death.

So an example of this would be the opioid crisis, which showed obviously unintended negative effects of the treatment. So opioids were great at managing pain, but they led to a surge in addiction and overdose deaths, which contributed to the increase in all cause mortality within certain demographics.

So we’d look at that now and we would say, okay, well, given that I don’t want to take any opioids because it’s probably not worth the risk. Considering that it’s about pain management, maybe there’s another alternative option. So this highlights the need to weigh the potential benefits of the risk of a treatment by considering its impacts on all cause mortality. You don’t want a medication that reduces your risk of death for one cause, but increases it for another. And all cause mortality is really one of the clearest examples of how medicine is all just a big risk reward calculation. Because death is such a clear end point that this provides a real opportunity for us to talk a little bit, um, about how these calculations need to be made because they need to be made all the time and, you know, that’s

the standard part.

so knowing the all cause mortality rate can certainly help you make more informed decisions about the treatments, the options that are being presented to you, and it allows you to sort of consider both the potential benefits as well as the risk and who you are and how you fit into all of that.

So in summary, I would say that all cause mortality is essential to know when you’re getting any kind of medical advice because it provides this baseline for understanding and interpreting all of these various risks and as well as telling you the benefits of the treatment and the intervention. So I hope that was helpful.

Emily Kaplan is an expert in strategy and communication. As the CEO and Co-founder of The Broken Science Initiative, she is building a platform to educate people on the systemic failings in science, education and health while offering an alternative approach based in probability theory. As the principal at The Kleio Group, Emily works with high profile companies, celebrities, entrepreneurs, politicians and scientists who face strategic communication challenges or find themselves in a crisis.

Emily’s work as a business leader includes time spent working with large Arab conglomerates in the GCC region of the Middle East looking to partner with American interests. Emily acquired Prep Cosmetics, expanded it to become a national chain and revolutionized the way women bought beauty products by offering novel online shopping experiences, which are now the industry standard. She was a partner in a dating app that used the new technology of geolocation to help interested parties meet up in real life. Emily developed Prime Fitness and Nutrition, a women’s health concept that focused on the fitness and diet needs of women as they age, with three physical locations. She was the host of the Empowered Health Podcast, and wrote a column in Boston Magazine by the same name, both of which focused on sex differences in medicine.

Emily is an award winning journalist who has written for national newspapers, magazines and produced for ABC News’ 20/20, Primetime and Good Morning America. She is the author of two business advice books published by HarperCollins Leadership. Emily studied Advanced Negotiation and Mediation at Harvard Law School. She has a Masters of Science from Northwestern University and received a BA in history and psychology from Smith College.

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

And more evidence that victory isn’t defined by survival or quality of life

The brain is built on fat—so why are we afraid to eat it?