Misrepresenting the results of clinical trials

By Malcolm Kendrick

In the frantic information world we now live in, few of us can be bothered to pay close attention to…well, pretty much anything. Yes, we have our own areas of interest. We know a great deal about certain things and will happily spend time and effort finding out more.

As for almost everything else ‘Give me a headline, it’s all I need. Life is too short.’ So, many important things pass most people by. Or, as Winston Churchill once remarked. ‘A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its boots on.’

Here is a headline for you, from 2017.

“Amgen Announces Repatha® (Evolocumab) Significantly Reduced The Risk Of Cardiovascular Events In FOURIER Outcomes Study.’

(I highlighted the word ‘events’)

Just to fill in a little background here. Repatha is the brand name of the drug evolocumab. It is an injectable LDL/cholesterol lowering agent. It lowers the LDL level to a far greater degree than statins. Therefore, in theory at least, it should reduce the risk of dying of cardiovascular disease to a far greater degree than statins.

Repatha was the first in a new class of LDL lowering agents, known as PCSK-9 inhibitors. There are now several of them. They only cost several hundred times as much as statins. Bargain.

To return to the headline. What it states – or appears to state – is that Repatha significantly reduces the risk of cardiovascular ‘events.’ If you read the whole paper, it expands on that statement. Explaining that there was a:

“15% reduction in the risk of the primary composite end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization.”

And a

“20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.”

These reinforce the finding that Repatha showed significant benefits on cardiovascular health… over and above anything that statins can provide. [Everyone on this trial also had to take a statin as this represents ‘standard’ treatment and could not ‘ethically’ be withheld].

Now, dear reader, I would like you to stop for a moment and take in a deep breath. Spend a few moments thinking about what you believe these headline statements mean.

I am unable to read your thoughts, but I am guessing you probably believe that Repatha reduces the risk of dying of a myocardial infarction (heart attack), and stroke, by twenty per cent – over and above statins.

How else are we supposed to interpret the statement: A “20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.”

Which does sound pretty damned good. At this point, I would like to make it clear that this statement is correct. I am not questioning the facts it presents – although I do have my doubts about the validity of the underlying research. Doubts that can wait for another day.

However, despite being unable to read your mind, I can pretty much guarantee that both statements don’t mean what you think they mean. Whatever you currently think they mean. Unfortunately, digging beneath the headlines does take some time. I hope you find it time well spent.

What is a cardiovascular event?

The issue to start with here is the following. What is a cardiovascular (CV) ‘event.’

A CV event can be many different things. It can be a heart attack. It can be a stroke. It can be an episode of angina. It can be a fatal heart attack, or a fatal stroke. Or atrial fibrillation, or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, or a heart arrhythmia. Or a rise in cardiac enzymes. It could be having a stent put in. The full list would be very long indeed.

In short, the term ‘CV event’ is broad enough to range from something you were unaware happened at the time, to something that kills you.

Even if you try to narrow things down to look at a specific CV event, these come in many different shapes and sizes too. A myocardial infarction, for instance. A man, or woman, clutches at their chest in agony, falls to the floor, then dies. This certainly happens. I would call this a ‘bad’ myocardial infarction a.k.a. heart attack. As bad as it gets.

How about a man, or woman, who has a stent put in?

A stent is a small latticework metal tube inserted in coronary arteries to open it up and improve blood flow, this technique has pretty much replaced coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

What most people do not know is that this procedure often results in heart muscle/myocardial damage. This is confirmed by the release of an enzyme called troponin. An enzyme that normally sits within myocardial cells, but if myocardial cells die, troponin is released into the bloodstream, where it can be measured with a blood test.

In almost 70 percent of cases, stent insertion can result in a troponin level considered high enough, in other situations, to diagnose a heart attack.

From the paper ‘Peri-Procedural Troponin Elevation after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease.’

“Despite the great efficiency and high safety, it should be emphasized that LM PCI* are challenging and highly invasive procedure. Periprocedural myocardial injury (Troponin (Tn) > 99th percentile) is frequently discovered after LM PCI, being recognized even up to 67% of patients using a standard Tn assay.”

*left main coronary artery percutaneous coronary intervention (a stent).

Did the patient know that they had, technically, suffered a heart attack during stent insertion? Were they even told? Should they have been? Discuss.

Leaving that issue behind, the main point I want to emphasize here is that cardiovascular ‘events’ come in many different shapes and sizes. And even something that sounds like it could be a single thing, e.g. a heart attack, can present in many different ways. From deadly, to something only discovered by a blood test.

All of which means that, when a clinical trial press release uses the word ‘events’, an urgent little alarm sounds within my brain. Awakening me to the fact that critically important information is quite deliberately being hidden from you, me, and everybody else. “Come Watson! The game is Afoot!”

The Game Of Obfuscation

There is a joke from the cold war era about two athletes picked to compete against each other. One from the Soviet Union, one from the US. This was to demonstrate which system was superior. Capitalism, or Communism.

The US athlete won.

Pravda, the main Soviet newspaper reported the result as follows: “Soviet athlete finishes runner-up in major international athletics event. US athlete finishes second from last.”

Let me take you back to one of the statements I copied earlier:

“15% reduction in the risk of the primary composite end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization.”

What do you think a primary composite end-point may be when it’s at home? Any idea?

Then we have the next one:

“20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.”

Almost everyone, including almost every doctor, reading the second passage would believe that cardiovascular death, due to myocardial infarction, or stroke, was reduced by 20 percent. And that is exactly, and precisely, what you are supposed to believe.

I, on the other hand, give a world-weary shrug, then set to reading the paper with a more skeptical eye. I ponder questions such as:

What the hell do they mean by a ‘serious key secondary end point’? What was the reason for this very carefully crafted choice of words?

I also wonder why this turned out to be the ‘serious’ end-point of the trial? Is the primary end-point not serious enough? If not, why not? In addition, we have three separate events mentioned: cardiovascular death, MI and stroke. Yet they are referred to as a ‘secondary end-point’ – singular. Aren’t these three different things? Shouldn’t these be three different end-points – plural.

What the hell do they mean by a ‘serious key secondary end point’? What was the reason for this very carefully crafted choice of words?

I pretty much know what you are thinking now. Why doesn’t Dr Kendrick get a life?

Well, to a somewhat depressing degree, this is my life. Or an important part of my life. Stripping apart clinical papers to try and understand what they really mean, rather than accepting them at face value. I do find it strangely satisfying. Like the conclusion to a murder mystery, or a Sherlock Holmes case.

Now, and having deliberately danced around it for a while, I am going to tell you how many cardiovascular deaths there were in those taking Repatha, and in those taking placebo. The very same trial that appeared to report a 20 percent reduction in CV deaths.

In the FOURIER trial, in those taking Repatha, there were 251 CV deaths.

In the FOURIER trial, in those taking placebo, there were 240 CV deaths.

A four percent increase in cardiovascular death in those taking Repatha.

Yes, read that again, then read it again, just to ensure that you have got it right. And no, I have not got the figures the wrong way round. You could say that these are the cardiovascular mortality data that did not bark in the night.

In the next article, running soon on BrokenScience.org, I am going to explain how the statement that there was a “20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke” can be true. When there were more CV deaths in those taking Repatha. They can’t both be right, can they? Well, gentle reader, of course they can.

References:

- Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease; The New England Journal of Medicine, May 4, 2017.

- Peri-Procedural Troponin Elevation after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease; Journal of Clinical Medicine, Dec. 28, 2022.

More From the Series

Setting Up The Trick

Research Manipulation Part I

Part 1

Surrogate End-Points

Research Manipulation Part II

Part 2

Falsely Reporting Success

Research Manipulation Part IV

Part 4

Looking Even Closer

Research Manipulation Part V

Part 5

Placebos – The (Not) Nothing Pill

Research Manipulation Part VI

Part 6

If Placebos Are Not True Placebos…Then What

Research Manipulation Part VII

Part 7

Placebos. Trial Blinding, and Biomarkers

Research Manipulation Part VIII

Part 8

The Replication Crisis, And Where Placebos Fit In

Research Manipulation Part IX

Part 9

An Existential Crisis?

Research Manipulation Part X

Part 10

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio

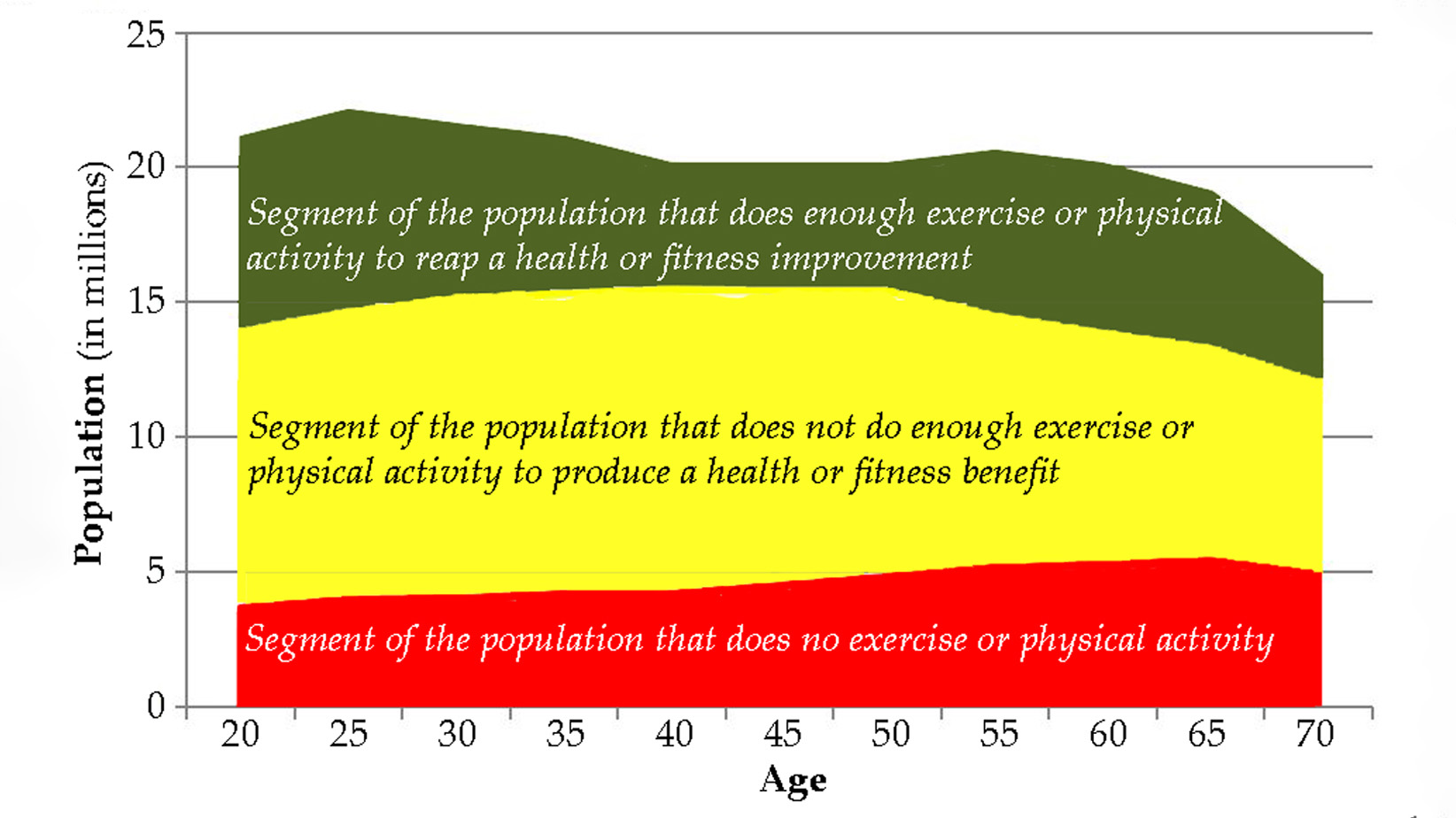

Maintaining quality of life and preventing pain as we age.