(Placebos Part C)

By Malcolm Kendrick

The first time I became aware that it is virtually impossible to ‘blind’ many (if any) clinical trials was with the use of AZT to treat AIDS. Here is a short section of a blog written by a doctor who lived through the AIDS crisis:

“The reason why randomized placebo controlled clinical trials are blinded, (so that neither investigator nor participant knows who is receiving placebo or active drug) is to minimize bias. Bias can influence the outcome that might incorrectly be attributed to a drug effect.

“But it’s impossible to blind a trial using AZT. The drug causes changes in routine blood counts that investigators need to see. Therefore, we must conclude that investigators could know who was receiving AZT or placebo.” [1]

The only thing here I would change is the word ‘could’. As in “we must conclude that investigators could know who was receiving the AZT, or placebo.” There can be no could about it. There is only would. Because it is simply not possible to believe that the investigators would be unaware of who was taking AZT. They had direct access to blood tests which told them.

In addition, the participants in this, the original AIDS trial, also knew if they were on the drug, or the placebo. Because many of them went to private labs to get blood tests to find out for themselves. At which point, many of those given the placebo went straight across the border to Mexico to get hold of (probably exceedingly dodgy) AZT.

No, this was certainly not the greatest trial ever. However, when the results came out it was widely proclaimed that AZT saved lives. But it didn’t. Which is the most positive thing I can find to say about the toxic and terrible drug called AZT. But it does highlight a major problem with using placebos in clinical trials. Which is that the effect of the active drug can often be seen, in one way or another.

Biomarkers – and other ways to know you are taking the active drug.

If you give someone a drug that lowers their blood pressure, then the blood pressure will be lowered. It’s what such drugs do. You can’t keep this a secret. A major part of any clinical trial on a blood pressure lowering agent will consist of repeatedly measuring the blood pressure, then writing it down. So, the investigators, in almost every case, will know who is taking the drug.

Patients can also measure their own blood pressure at home if they want to. “Oh look, it went down when I started on the clinical trial, I wonder what that could possibly mean.” They can also go to their GP for a check-up.

In much the same way, if you give a drug that lowers blood sugar levels, this reduction in blood sugar will be seen. Anyone can buy a relatively cheap machine to measure their own blood sugar level. Or pop along to your family doctor for a HBA1c test.

If you are studying a cholesterol lowering agent the level will go down in those taking the drug. You certainly cannot hide this from the investigators. In fact, you cannot hide it from the participants either. The simple fact is that if you give a drug which has a measurable effect (leaving aside side-effects) then ‘blinding’ is impossible.

A few years ago, I was invited to give a talk at the Scottish Lipid Society, believe it or not, considering my views on statins and cholesterol lowering in general. Another talk was given by the UK lead investigator on the FOURIER study. A trial I have written about at length.

At one point, the lead investigator mentioned that a trial participant told him they knew they were taking the placebo. When asked how, the participant said “Because my LDL/cholesterol did not go down.” He had seen the result of a blood test, taken at his GP surgery.

So, yes, he knew. His GP knew, and the investigators obviously knew. Everyone knew. Yet this trial was still published claiming to be fully double-blinded. How many other participants knew they were taking a placebo or the active drug? There are no studies on this. But my guess would be that almost everyone finds out, one way or another.

The official party line is that no-one has a clue. Blinding is always perfect. But if you never ask the question “Did you know you were taking the drug, or the placebo?” you can always claim that blinding was perfect. “Hey, no-one said anything to me.”

At this point, hands up anyone who truly believes that an average human being can take part in a clinical study, in some cases lasting up to five years, without needing to know what they are taking. And then finds out. Also, hands up anyone who does not believe the investigators look at various test results and conclude that the participant they are speaking to is on, or not on, the drug.

Once anyone knows, blinding has gone, and bias enters the equation. Which is the exact thing that blinding is designed to stop.

How can this affect the trial results themselves?

Some trial results cannot be biassed. If someone dies, they are dead.

However, there are many other things which are far from black and white. A small and transient stroke, for example. The symptoms can be vague. A period of confusion, or some difficulty standing up. A bit of numbness and tingling. The brain scan shows a few things that may, or may not, correlate to the symptoms. There is no definitive test. One doctor may say stroke, another may not.

What about a heart attack? Some chest pain that lasted an hour or so. The ECG shows a couple of signs that may or may not be consistent with an infarction. The heart enzymes rise a bit. Heart attack, or not?

If you think it is straightforward diagnosis then you really ought to try reading the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). There are four major types of myocardial infarction, with many pages on myocardial injury, that could be, or could not be an infarction. The documents runs to over thirty pages.

“Arriving at a diagnosis of MI using the criteria set forth in this document requires the integration of clinical findings, patterns on the ECG, laboratory data, observations from imaging procedures, and on occasion pathological findings, all viewed in the context of the time horizon over which the suspected event unfolds.” [2]

Of course, a full-blown stroke or a major heart attack are straightforward. But the grey areas cover a very large percentage of your trial population. The decisions are complex. It requires “the integration of clinical findings, patterns on the ECG, laboratory data, observations from imaging procedures, and on occasion pathological findings.”[2]

If one of the clinical findings you take into account is the cholesterol level then, inevitably, you are less likely to diagnose a stroke or a heart attack in those with very low levels.

Therefore, the trial participants taking an LDL/cholesterol lowering drug will be significantly less likely to have a minor stroke or heart attack diagnosed, than those taking a placebo.

This is exactly how bias enters clinical trials. Blinding is the main technique to prevent this. But if blinding does not truly exist…then what? Then the results of your trial become unreliable. People start seeing what they want to see – as people tend to do. And what they see will inevitably favor the drug, over the placebo. And the problems with blinding do not stop here.

Official unblinding

Imagine you are taking part in a clinical trial using a cholesterol lowering agent. What do you think happens if you are admitted to hospital, for whatever reason?

“In cases of medical emergencies or serious medical conditions that occur while a participant is taking part in a study, the participant may not be able to be treated adequately unless the doctors know which treatment they have been receiving. In such situations, unblinding may be necessary.” [3]

Yes, of course, the medical staff have to know. If not, how can they possibly treat you? This new experimental drug may have interactions with other drugs they want to prescribe. It may have effects on the heart, or the lungs, or kidneys. You could be killed by ignorance.

So, the medical staff will be told if you are taking the drug, or the placebo. They also need to know exactly what that drug is, and what it does. At which point, they too are unblinded. And the pharmaceutical company also knows and can therefore ‘advise’ on how to manage the patient. At which point the trial participant, the investigators, the pharma company, and the medical staff are all unblinded.

Summary

The double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial is a myth. It is a convenient myth for everyone involved in clinical trials to believe in. Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil. The reality is that in most clinical trials blinding is imperfect, at best. And completely ineffective, at worst.

This may not matter much in trials on, say, painkillers. But when you are looking at major clinical events such as heart attacks and strokes, unblinding is a massive problem. It allows clinical bias to enter, and this bias can easily overwhelm the results, to the point where they can become virtually meaningless. Which I will look at next.

References:

- Remembering the Original AZT Trial; Joseph Sonnabend, MD; POZ; January 29, 2011.

- Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018); Kristian Thygesen, et al., Circulation; August 24, 2018.

- Within-trial decisions: Unblinding and termination; EUPATI website. Update November 11, 2016.

More From This Series

Setting Up The Trick

Research Manipulation Part I

Part 1

Surrogate End-Points

Research Manipulation Part II

Part 2

Deliberate Obfuscation

Research Manipulation Part III

Part 3

Falsely Reporting Success

Research Manipulation Part IV

Part 4

Looking Even Closer

Research Manipulation Part V

Part 5

Placebos – The (Not) Nothing Pill

Research Manipulation Part VI

Part 6

If Placebos Are Not True Placebos…Then What

Research Manipulation Part VII

Part 7

The Replication Crisis, And Where Placebos Fit In

Research Manipulation Part IX

Part 9

An Existential Crisis?

Research Manipulation Part X

Part 10

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio

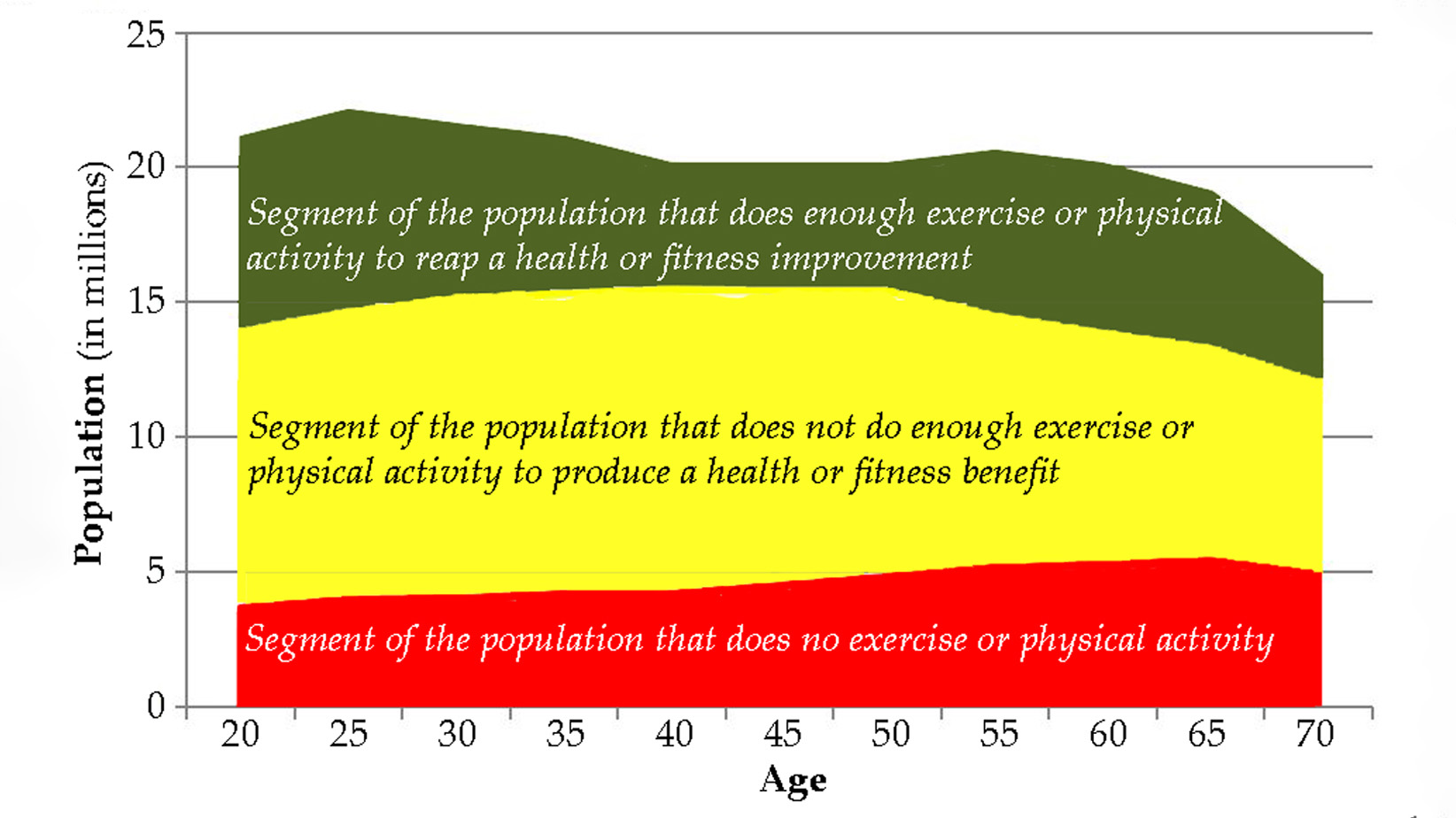

Maintaining quality of life and preventing pain as we age.