By Malcolm Kendrick

A few years back I was told that, in the statin clinical trials, the rate of adverse effects was always the same for the placebo, and the statin. No matter the absolute rate. This was also true for the rate of participants withdrawing from the trials. Always the same between the statin arm and the placebo arm – no matter what the overall rate may be.

To make more sense, these statements perhaps require a little more explanation and background.

In many large clinical trials participants are first randomized into two equal groups, then given either a placebo, or the active drug. Which is why such trials are usually called placebo controlled randomised clinical trials (PCRCT). In reality this acronym is usually shortened to randomized controlled trials RCTs. [Not all clinical trials use placebos, and less and less do so].

If a trial uses a placebo, they are also supposed to be ‘double-blind’. Which means that neither the trial participants, nor the investigator, should know who is taking the placebo or the active drug. For this to work, the drug and placebo should be the same size, the same color, have the same taste, and so on.

However, as I pointed out in the last article, there are no rules as to what goes inside a placebo… cyanide? Which may seem unbelievable, but it is true. So, we simply have to trust that pharmaceutical companies would never, ever, put things into placebos that could cause any adverse effects, or other harm. “Cross my heart and hope to die… Sorry, hope not to die.”

Now, I don’t know about you, but…we already know placebos can be filled with noxious substances.

Taking you back to the statin trials… of which there have been many.

The first thing to say here is that you would expect there to be a different rate of adverse effects between one statin and another. Also, between the higher and lower doses of the same statin.

It is also true you might expect that placebo related adverse effects will vary – a bit, if not a lot. This is mainly because there is no standardized way of asking about adverse effects. Or even which adverse effect you should ask about. Once again, somewhat unbelievably, you can ask what you like, about any adverse effect you like:

Researcher trial 1:

“Have you suffered more headaches since the start of the trial?”

Researcher trial 2:

“Have you suffered more severe headaches since the start of the trial?”

Clearly it is possible to find there will be a very different number of ‘headaches’ reported depending on which question you choose to ask.

Having got that out of the way. You would still expect that the total rate of adverse effects reported from taking a placebo would be roughly the same – in all clinical trials. Three percent report headaches, five percent muscle pain or tiredness etc.

In fact, by now, you would think we would know the exact percentage of every adverse effect caused by taking placebos. After all, a placebo is an inactive sugar pill… isn’t it? And there have been thousands of ‘placebo controlled’ clinical trials. We should have pretty accurate data – instead of no data at all.

Maybe, though, placebos are not inactive sugar pills.

Statin trial adverse effects and discontinuation

Almost ten years ago I was so concerned about the new guidance on statins in the UK that I wrote a letter to the Chairman of the guideline committee, known as NICE (National Institute for health and Care Excellence). It was co-signed by a few others such as:

- Sir Richard Thompson, President of the Royal College of Physicians.

- Professor Clare Gerada, Past Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners and Chair of NHS Clinical Transformation Board.

It included this section about adverse events:

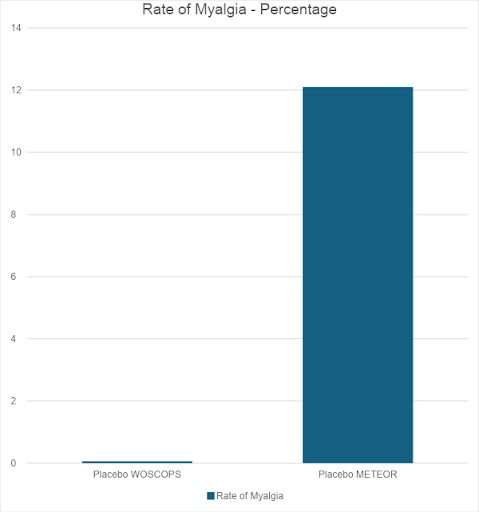

“The levels of adverse events reported in the statin trials contain worrying anomalies. For example, in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS, the first primary prevention study done), the cumulative incidence of myalgia was 0.06% in the statin arm, and 0.06% in the placebo arm.

“However, the METEOR study found an incidence of myalgia of 12.7% in the Rosuvastatin arm, and 12.1% in the placebo arm. Whilst it can be understood that a different formulation of statin could cause a different rate of myalgia, it is difficult to see how the placebo could, in one study, cause a rate of myalgia of 0.06%, and 12.1% in another. This is a two hundredfold difference in a trial lasting less than half as long.” [1]

Myalgia means, essentially, muscle pain.

I thought I would put the myalgia figures from the two different trials into a graph format, showing the rate of myalgia in the WOSCOPS vs. METEOR. And remember, this is the rate of myalgia with placebo. The inactive sugar pill – supposedly.

I had to stretch this graph vertically. Otherwise, the placebo rate of myalgia in the WOSCOPS study could not be seen. It merged into the line for zero.

What are we to make of this? What can we make of this?

Unfortunately, it is difficult to drill down into the adverse event data in any great detail, because most of it was not published anywhere – and still is not. The group who hold the statin data, the Cholesterol Treatment Triallists collaboration (CTT) in Oxford will not allow anyone to see the data that they hold. It is still considered confidential.

As with many things I write, most people find it almost unbelievable that medical research data are kept confidential – for decades – and will not be released for review by other researchers. In order to make it clear that I am not some mad conspiracy theorist in making this claim, I feel the need to provide some evidence.

Below, is the start of an e-mail chain between Maryanne Demasi, at the time a producer working for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. She made the mistake of putting together a TV program which was critical of statins.

For which public service she was ruthlessly attacked and lost her job, and very nearly had her PhD stripped from her – with utterly bogus accusations made. If you want to read more about this sorry saga, for some more facts, and supporting references, you can go here.

To: Enquiries at CTT

From: Maryanne

Sent: 22 September 2013 05:05

Subject: URGENT COMMENT NEEDED PLEASE: ABC TV AUSTRALIA

Hi, I am a medical reporter for ABC TV AUSTRALIA, and I am doing a report on statins in primary and secondary prevention.

I have interviewed Harvard Dr John Abramson about the overuse of statins within the population and also the lack of transparency of data when it comes to clinical trials.

In the interview he mentions the CTT collaborators being one group who have access to individual data but will not share their data with the public or other researchers even though they’ve been asked.

Prof Rita Redberg from University of California San Francisco supports these statements.

I would like a comment from CTT collaboration regarding Dr Abramson’s and Prof Redberg’s statements please?

Why has the CTT Collaborations refused to release all the data requested of them?

Kind Regards

Maryanne Demasi

Producer

ABC TV AUSTRALIA

The initial response from Professor Colin Baigent was:

Dear Maryanne

Drs Abramson and Redberg are incorrect in stating that the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration has not shared data on the effects of statin therapy in healthy people.

Their communication ended with the following note of a telephone conversation:

PHONE CALL WITH COLIN BAIGENT: NOTES

I had a follow up conversation with Colin. He stressed that while the CTT made an agreement with the drug companies not to give full disclosure of the individual data to third parties, the CTT had a very important role in providing doctors with the best information available. He hoped that my report did not undermine the workings of the CTT.

So, as it turned out Drs Abramson and Redberg were, in fact, correct. The fact is that the CTT had not, still has not, and it seems never will share the individual patient data from the statin clinical trials with anyone. But that’s okay, because as everyone knows, the best way to do high quality science is to keep your data locked away and never let anyone else see it. Ever.

Returning to the letter I wrote to NICE, it carried on…

“Furthermore, the rate of adverse effects in the statin and placebo arms of all the trials has been almost identical. Exact comparison between trials is not possible, due to lack of complete data, and various measures of adverse effects are used, in different ways.

However, here is a short selection of major statin studies.

AFCAPS/TEXCAPS:

Total adverse effects: lovastatin 13.6%: Placebo 13.8%

4S:

Total adverse effects: simvastatin 6%: Placebo 6%

CARDS:

Total adverse effects: atorvastatin 25%: Placebo 24%

HPS:

Discontinuation rate*: simvastatin 4.5%: Placebo 5.1%

METEOR:

Total adverse effects: rosuvastatin 83.3%: Placebo 80.4%

LIPID:

Total adverse effect: Pravastatin 3.2%: Placebo 2.7%

JUPITER:

Discontinuation rate: Rosuvastatin 25%: placebo 25%.

Serious adverse events: Rosuvastatin 15%: placebo 15.5%

WOSCOPS:

Total adverse effects: Pravastatin 7.8%: Placebo 7.0%

Curiously, the adverse effect rate of the statin is always very similar to that of placebo. However, placebo adverse effect rates range from 2.7% to 80.4%, a thirty-fold difference.” [1]

*discontinuation rate is the number of participants who left the trial – for whatever reason.

Currently it is claimed, repeatedly, that statins have no more adverse effects than placebo. And if you look at the list above, this appears to be true. But how was this particular magic trick achieved?

How can total adverse effects from placebo vary from 2.7% to 80.4%. How can the adverse effects from the statin and the placebo always be almost exactly the same, when the absolute rates vary thirty-fold. How can the rate of myalgia reported in two trials differ by two hundred-fold. I present you with three possibilities:

- A quite remarkable coincidence p<0.000000001

- The data were falsified

- Placebos do not contain inactive substances

We already know that possibility number three is true. So, it seems most likely to be the answer. But maybe there is something else going on here that I have not considered. If so, I would be interested to know what it might be.

References:

- Concerns about the latest NICE draft guidance on statins; Sir Richard Thompson, Dr Malcolm Kendrick, et al.; Letter to the chairman of the National Institute for health and care Excellence (NICE); June 10, 2014.

More From This Series

Setting Up The Trick

Research Manipulation Part I

Part 1

Surrogate End-Points

Research Manipulation Part II

Part 2

Deliberate Obfuscation

Research Manipulation Part III

Part 3

Falsely Reporting Success

Research Manipulation Part IV

Part 4

Looking Even Closer

Research Manipulation Part V

Part 5

Placebos – The (Not) Nothing Pill

Research Manipulation Part VI

Part 6

Placebos. Trial Blinding, and Biomarkers

Research Manipulation Part VIII

Part 8

The Replication Crisis, And Where Placebos Fit In

Research Manipulation Part IX

Part 9

An Existential Crisis?

Research Manipulation Part X

Part 10

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Metabolic Flexibility to Burn Fat, Get Stronger, and Get Healthier

Expanding Horizons: Physical and Mental Rehabilitation for Juveniles in Ohio