(Placebos Part E)

By Malcolm Kendrick

There was a time when doctors could make treatment decisions based on their knowledge and experience. Over time various authorities began to feel that this was potentially dangerous. What if their knowledge was out of date, or wrong? What if their experiences were biased. The patient may not receive optimal care. They could be harmed rather than helped.

Driven by such concerns, the Evidence Based Medicine (EBM) movement gathered pace. This was, at heart, an attempt to ensure that all medical conditions could be treated in the best possible way, using high level evidence, wherever possible.

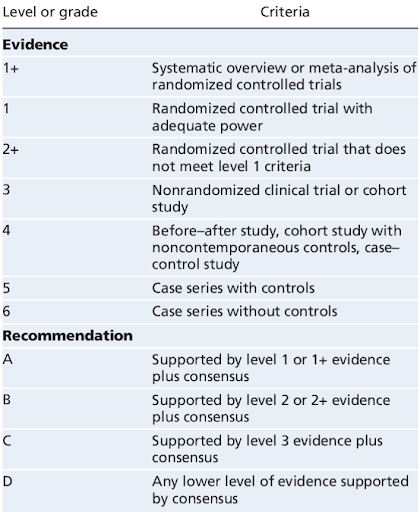

The evidence itself has also been graded in various ways. Below is a typical table. What is not clear is if one set of grade 1+ evidence is more powerful than ten sets of grade 3. I think it probably is.

As EBM has grown, more guidelines have been written, protocols created, management plans developed…then more and more guidelines. A ‘brave new world’ of algorithm-based medicine has arrived.

If a patient has condition x, then use drug y. If drug y is not effective, add in drug z. If the patient is African American start with drug c, then b. Add in drug e if necessary. Some of the guidelines now stretch to hundreds of pages and, for all healthcare professionals, it has become increasingly difficult to set guidelines aside and use their own judgment.

It can be argued that this has all been a good thing, although my belief is that turning your medical workforce into ‘algorithm operators’ brings with it significant harms. What is the point of training people for years, and years, if they cannot use their own judgment? It is both demotivating, and disempowering.

What is the point of training people for years, and years, if they cannot use their own judgment? It is both demotivating, and disempowering.

Leaving aside the issue of workforce morale, what of the evidence itself. There are always issues with bias in clinical trials, and the possibility of manipulating the results. Both of which clearly occur.

However, there is a deeper level problem in play here. What is the evidence supporting the use of randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) themselves. The very highest level that we use.

You may think it is almost mad to question this. Of course we need to use RCTs. What else is there?

I do not dispute the need for scientific rigor in creating evidence. Nor do I dispute the need for removing subjectivity and, as far as possible, controlling bias and manipulation. We should not make completely unevidenced claims for treatments.

So yes, we do need some form of randomisation. By which I mean we need to try and ensure that those receiving a new treatment should be compared with another group – who are as similar as possible – who do not receive that treatment.

Or, to put this another way. You cannot give a drug to healthy thirty-year-olds, with no health problems; and withhold the drug from seventy-year-olds with three chronic illnesses. Then claim that the drug was responsible for the improved health in the thirty-year-olds. The best way to remove that form of bias is through randomization.

In addition to randomization, you need some form of control and oversight of a clinical trial. If you do not have randomization and ‘control, you do not have science. You are just making things up. But, what of placebos?

What of placebos?

For many years it has been widely accepted that if you give someone a pill which contains no active ingredient, it will create positive effects. The ‘placebo’ effect. The same degree of ‘passive’ benefit will also occur if you give someone an active drug. Therefore, in a clinical trial, you need to ensure that your drug demonstrates benefits, over and above, the underlying placebo effect.

This has generally been done by giving a placebo to those not taking the active drug, to balance out the placebo effect in both groups. The use of placebos is considered to be a critical building block in several of the most influential and important clinical trials ever done.

If you are going to have a placebo arm, you cannot let the participants know if they are taking the placebo, or the active drug. This is because, it is further assumed, that if people know they are taking a placebo it will negate any benefit. The placebo effect only occurs when people think they are taking an active drug.

Which means that you have to ‘blind’ the trial participants – and those running the trial – as to who is getting the placebo, or the active drug. Otherwise, they may see benefits, or harms, where they do not exist. But there are two major assumptions here.

- That the placebo effect exists for almost all conditions

- That the placebo effect only works if people believe they are taking an active drug (to be dealt with in another article)

There were almost no placebo-controlled studies done prior to WWII. Not long after that they became the gold standard. In large part resting on one very influential paper by Henry K. Beecher, as discussed in the paper ‘The Powerful Placebo Effect: Fact or Fiction?’

“In 1955, Henry K. Beecher published the classic work entitled “The Powerful Placebo.” Since that time, 40 years ago, the placebo effect has been considered a scientific fact. Beecher was the first scientist to quantify the placebo effect. He claimed that in 15 trials with different diseases, 35% of 1082 patients were satisfactorily relieved by a placebo alone. This publication is still the most frequently cited placebo reference.” [1]

But, from the same paper:

“Beecher’s ‘The Powerful Placebo,’ published in 1955, has been a seminal and most influential paper. It is still the most frequently cited placebo reference. This is amazing, as none of the original trials cited by Beecher gave grounds to assume the existence of placebo effects. The reanalysis of a similar classic German placebo survey gave the same results. No placebo effects could be found.”

In addition

“Placebo interventions are often believed to improve patient reported and observer reported outcomes, but this belief is not based on evidence from randomised trials that compare placebo with no treatment.” [2]

That quote from the paper ‘Placebo treatment vs. no treatment’ Which concludes:

“There was no evidence that placebo interventions in general have clinically important effects. A possible moderate effect on subjective continuous outcomes, especially pain, could not be clearly distinguished from bias.”

It is a strange thing that the placebo effect is widely considered to be an established ‘fact’. However, when it has been subjected to objective study, it does not actually exist. It is one of many ‘facts’ in medicine that feels right, so it has been accepted without real scrutiny. To quote Mark Twain.

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

About the only area where placebos have been found to, possibly, have some effect is on subjective measures such as the perception of pain. Here from the paper ‘Is the Placebo Powerless? — An Analysis of Clinical Trials Comparing Placebo with No Treatment’:

“Although placebos had no significant effects on objective or binary outcomes, they had possible small benefits in studies with continuous subjective outcomes and for the treatment of pain.” [3]

Why does this matter?

It could be argued that if there is no placebo effect, then double blind placebo-controlled trials have simply been a waste of time and money. No harm done, nothing to see, move along. Yes, we could have had ‘do nothing’ arms in clinical trials, but we would have just ended up with much the same results.

And if you think there would have been no difference, how do you know? The only way to know, for sure, would be to repeat the exact same trial using an active drug and a ‘no treatment’ arm. But this type of trial has never been done.

And there are several other problems from assuming the need to use placebos. Just to look at two of them:

The first problem is that the requirement for placebo arms adds vastly to the cost of doing randomized trials. Getting a placebo tablet designed and manufactured often costs so much that it is beyond the reach of anyone other than a large pharmaceutical company.

“Acquiring placebos, including repacking, requires a substantial part of the overall trial budget; data from our survey suggests that this could be as much as 10% of the overall trial costs. This is in line with the case report from Curfman and colleagues, stating that the costs for placebos were US$ 900,000. Christensen and Knop also reported that “a drug company charged an extraordinary amount of money for providing a simple placebo tablet, effectively preventing the planned clinical trial from going ahead.” [4]

As with many things, the industry makes it almost impossible for anyone else to carry out large scale clinical trials. This is made worse by the fact that if an investigator wants to do a study that is not in the interest of the original pharmaceutical company, they’re considerably less likely to be provided with any placebo.

“Studies with a hypothesis in the interest of the original manufacturer appeared more likely to obtain placebos from the drug manufacturer (18 of 49; 37%) compared to RCTs for which the hypothesis was not in the manufacturer’s interest (5 of 29; 17%; odds ratio: 2.79.)” [4]

However, the most significant problem here is one mentioned in an earlier article. We do not know what goes into placebos. There are no rules, no control. In many cases, placebos are known to have contained substances that can lead to highly unpleasant adverse effects.

Getting a placebo tablet designed and manufactured often costs so much that it is beyond the reach of anyone other than a large pharmaceutical company.

The ’excuse’ is that this helps with blinding. In that, if the placebo had no adverse effects, the investigators would know which trial participant was taking the active drugs.

Whilst it is possible to have some sympathy with this view – although there are many other ways that blinding can be sidestepped – what this also does is to significantly distort the bias and the potential benefits of a drug. If you compare a drug with doing nothing. You can clearly see what harmful effects a drug will have.

If, on the other hand, you compare a drug with a placebo containing substances that have many potential adverse effects, then the drug’s adverse effects will be camouflaged. The benefits will be overestimated.

Summary

Many of the highly influential randomized controlled trials that underpin Evidence Based Medicine (EBM), and therefore dictate a vast amount of current patient care, were done using an active drug vs. placebo.

However, the assumption that there is a real placebo effect is based on no real evidence at all… other than in subjective symptoms e.g. pain. There is no evidence, for example, that a placebo can lower blood sugar levels, nor influence binary outcomes. Ergo, the basis for a hugely important building block of EBM simply does not exist.

Most importantly, it is highly likely that the use of placebos will have resulted in greater benefit being reported than actually exists. It will have distorted the benefit to harm ratio in favor of the drug. The use of placebos has trapped us with an evidence base that rests upon very shaky foundations indeed, and yet it is all we have. I believe this to be an existential crisis for medicine.

References:

- The Powerful Placebo Effect: Fact or Fiction?; Gunver S Kienle, Helmut Kiene; Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; August 20, 1997.

- Placebo treatment versus no treatment; A Hróbjartsson, P C Gøtzsche; Cochrane Library; January 20, 2010.

- Is the Placebo Powerless? — An Analysis of Clinical Trials Comparing Placebo with No Treatment; Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, M.D., and Peter C. Gøtzsche, M.D.; The New England Journal of Medicine; May 24, 2001.

- A meta-research study revealed several challenges in obtaining placebos for investigator-initiated drug trials; Benjamin Speich, Patricia Logullo, et al.; Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; November 13, 2020.

More From This Series

Setting Up The Trick

Research Manipulation Part I

Part 1

Surrogate End-Points

Research Manipulation Part II

Part 2

Deliberate Obfuscation

Research Manipulation Part III

Part 3

Falsely Reporting Success

Research Manipulation Part IV

Part 4

Looking Even Closer

Research Manipulation Part V

Part 5

Placebos – The (Not) Nothing Pill

Research Manipulation Part VI

Part 6

If Placebos Are Not True Placebos…Then What

Research Manipulation Part VII

Part 7

Trial Blinding, And Biomarkers

Research Manipulation Part VIII

Part 8

The Replication Crisis, And Where Placebos Fit In

Research Manipulation Part IX

Part 9

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

The iceberg beneath “normal” blood sugar numbers

What Addiction Medicine Missed – and What Bitten Jonsson’s Work Reveals