Explaining how a clinical trial can report success – when there is none.

By Malcolm Kendrick

Key point: If the most important end-point is not mentioned in the title of a clinical trial, or in the abstract, it did not change. Always search for that which should be there – the dog that did not bark in the night.

In the last article I highlighted the FOURIER clinical trial on Repatha, which claimed there was a:

“20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.”

When the figures on CV death were that:

In those taking Repatha, there were 251 CV deaths.

In those taking placebo, there were 240 CV deaths.

Both statements are true, if true is the right word. How about correct? Or are supported by the evidence. But how can it be that two apparently contradictory ‘facts’ co-exist side by side? Well, we need to start by looking at end-points.

What is an end-point?

The end-point of a clinical trial can also be called the ‘outcome’. You have a drug you believe reduces death from a medical condition. You find a group of people with this medical condition e.g. high cholesterol levels, you then randomize your trial participants into two evenly matched groups. You give one half of the group the active drug, and the other half a placebo. (More on problems with placebos in later articles).

You then wait and see how many die in both groups. If the number dying in the placebo group (vs the treatment group), is greater than you would expect by chance (less than a one in twenty chance p<0.05%), you have yourself a statistically significant result. At which point you claim dramatic success, then make billions selling your drug.

The end-point of a trial like this is often stated as taking drug x resulted in a ‘reduction in x percent of deaths’. Ten percent, twenty percent, thirty percent and so on. This can also be presented as the ‘reduction in overall mortality’.

Why the need for many different endpoints?

Many trials do not use death as their primary endpoint. If you develop a new pain killer, the end-point you want to measure will be… reduction in pain. If you have an antidepressant, you measure reduction in depression.

However, getting back to dead, or not dead, whilst this is the ‘number one’ end-point of many cardiovascular trials, it is also the hardest to achieve. This is because, whilst around forty percent of people die of cardiovascular disease, the other sixty percent do not.

Therefore, a drug designed to stop people dying of CV disease can only reduce death in forty percent of the total population (unless it does something else beneficial you didn’t expect).

Which means that achieving a statistically significant reduction in overall mortality, whilst only reducing deaths in a maximum of forty percent of that population, can be a tough ask.

This remains true even if you single out participants for your trial who are more likely to die from CV disease e.g. people who have already suffered a heart attack, or stroke in the past. In this case around 80% of this population would be likely to die from CV disease. [Figures used here for illustrative purposes only].

Given this difficulty, you may decide to narrow down the end-point of your clinical trial to look at cardiovascular mortality, not overall mortality. As it will be easier to achieve. But… warning Will Robinson, warning! You have now moved to a place where it is possible to reduce CV mortality, whilst having no effect on overall mortality.

… you may decide to narrow down the end-point of your clinical trial to look at cardiovascular mortality, not overall mortality. As it will be easier to achieve. But… warning Will Robinson, warning! You have now moved to a place where it is possible to reduce CV mortality, whilst having no effect on overall mortality.

For example, your drug reduces the rate of fatal heart attacks by twenty percent but simultaneously causes an equal and opposite number of liver failure deaths. While there will be a clear benefit on CV deaths, overall mortality would not budge Which does not generally represent a successful trial outcome. People do not take medication simply to swap one cause of death, for another. At least not as far as I know.

Which is why, whenever I look at papers on cardiovascular drugs, I begin by looking for the impact on overall mortality. If it is not mentioned in the title, the abstract, or the discussion, then I know it did not change. It can usually be found in the paper, somewhere, although it may well be hidden within an appendix, or a table that can only be accessed several levels down. Page not found.

If we go back to the Repatha study for a moment, the actual figures on overall mortality were, as follows:

In those taking Repatha, there were: 444 deaths.

In those taking placebo, there were: 426 deaths.

Moving down a level or two

As you would expect, therefore, the press release for the FOURIER study did not mention overall mortality – as it went up rather than down. Instead, what we got was. ‘Amgen Announces Repatha® (Evolocumab) Significantly Reduced The Risk Of Cardiovascular Events In FOURIER Outcomes Study.’

CV mortality was not mentioned either, for exactly the same reason – it went up, not down. Instead, the word ‘events’ was used.

What is an event? As mentioned in the previous article, a cardiovascular event can be almost anything that lies within the realm of cardiovascular disease. In the case of the FOURIER study there were five main types of ‘event’, or end-points which they decided to measure:

- Cardiovascular death

- Myocardial infarction

- Stroke

- Hospitalization for unstable angina

- Coronary revascularization

Right here is where the game of obfuscation plays out. What Amgen decreed, before the trial began, was that they were going to take these end-points and link them all together to form a ‘combined’ end-point. Not one end-point, but five. This was to be the primary trial outcome.

Why? Well, there are many reasons, although none of them have anything much to do with pushing forward the boundaries of medical knowledge. They are mainly to do with saving time, and money, and increasing profit.

In this case, three of the events are reasonable. CV death, MI and stroke. [Not, you will note, fatal MI or fatal stroke – and this too is important].

As for the other two. Hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization (putting in a stent). These are not true CV events. They are clinical decisions. To admit, or not, with angina. To put in a stent, or not. As such they are immediately subject to bias.

Now, I may know what some of you are thinking here. Aren’t drug trials supposed to be double blind? Double blind means that neither the trial participant, nor the treating doctor, knows if the participant is taking the drug, or the placebo. So bias is eliminated.

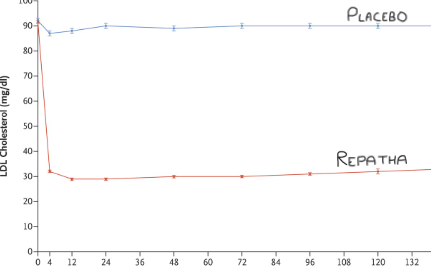

There are two problems here. The first is that Repatha lowers the LDL by more than sixty percent. Down to levels not normally seen in living human beings. (See graph).

Thus, everyone who catches sight of a blood test result, doctor, or patient, knows exactly who is on the drug, and is not. In addition, if you are admitted to hospital, whilst taking part in a clinical trial, the medical team needs to know you are a trial participant, also if you are taking the drug, or placebo. This is done for safety reasons. Ergo, if you need medical attention whilst taking part in a study, blinding evaporates.

And once blinding has gone, the decision to stent, or not stent, will inevitably be influenced by the LDL level. Very low LDL level…well, they can probably get away without a stent, because they are at low risk.

Then there are decisions about whether or not someone has had a stroke. You might think this is very clear cut. In some cases it is. Loss of power on one side, drooping mouth, loss of vision, very serious. However, many strokes are far from black and white. A mild ‘event’ may have been a stroke, might not. There is no definitive test.

As for an MI, once again, things are far from black and white. Here from the article ‘Misclassification of Myocardial Injury as Myocardial Infarction.’

“With the widespread introduction of high-sensitivity troponin assays, the detection of myocardial injury in hospitalized patients has become more frequent; currently, the most common cause of troponin elevation may now be nonischemic myocardial injury rather than acute myocardial infarction (MI). The detection of abnormal troponin concentrations in the absence of ischemia has led to confusion; this circumstance has frequently been labeled as “troponinemia,” “troponinitis,” or incorrectly as a type 2 MI (T2MI; for which coronary ischemia is a prerequisite) Misclassification of Myocardial Injury as Myocardial Infarction.”

Maybe a bit heavy on the jargon? If so, just focus on the words ‘misclassification’, and ‘confusion’. In other words it is perfectly possible to state that someone has had an MI, when they haven’t. And when blinding has gone, bias enters.

So, deep breath, this stuff just goes on and on doesn’t it… this is the truth getting its boots on. A long process with many knots to be untangled, then done up again…

…in the FOURIER trial we have five end-points combined into one. Four of which are subject to bias, and two of them are not really clinical events. Cardiovascular death is the most significant end-point, by a long way. It is also the least subject to bias. It was also the one that remained unchanged. [Although, as I will discuss in the next article, it was far from untampered with].

Adding all the end-points together

There were two key advantages to the trial sponsor (the pharmaceutical company) using many different end-points and adding them together. Advantage number one is you get a lot more end-points to measure, so it becomes easier, and quicker, to demonstrate statistical significance. [This trial was terminated early because the number of pre specified end-points was reached early. It was planned to last 3.6 years and only lasted 2.2].

The second advantage is that you get to add together a whole bunch of outcomes, ranging from from CV death to coronary revascularization, and suggest, or claim, or pretend, that they are of equal significance. Fifty stents plus one CV death, that is fifty one events. Fifty CV deaths plus one stent is also fifty one events….really?

Fifty stents plus one CV death, that is fifty one events. Fifty CV deaths plus one stent is also fifty one events….really?

Equally, a fatal myocardial infarction counts exactly the same as a non-fatal myocardial infarction. You think? Yes, no weighting was required here. An event is simply an event.

So, how many heart attacks do you think there were in the placebo arm of the FOURIER trial?

The answer is six hundred and thirty nine – 639

How many fatal heart attacks?

The answer is thirty – 30

Which number is larger? Which number should carry greater weight?

The biggest number of all, of course, was the number of revascularization procedures. Of which, in the placebo group, there were nine hundred and sixty five – 965. Which means that there were four times as many stents put in, as there were total cardiovascular deaths.

By now you should be able to see exactly where this is going. You add CV deaths, MIs, strokes, hospitalisation with angina, and stents together and you get 1,563 ‘events’ in the placebo group. Do the same for the Repatha group and you get 1,344 ‘events’. (Hazard Ratio 0.85 CI [0.78 – 0.92] P < 0.001) aka a 15% reduction in the composite end point, described as a:

“15% reduction in the risk of the primary composite end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization.”

If you do the same for the more restricted combined end-point of CV deaths, MI and stroke, you get 1,013 vs. 816 Placebo vs. Repatha. (Hazard Ratio 0.80 CI [0,73 – 0.88] P < 0.001]. This was described as a…

“20% reduction in the risk of the more clinically serious key secondary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.”

By measuring several different events, and adding them all together, and pretending that they are all of equal significance, you can reduce the combined end-point, without having any effect on the most important ‘event’ within that combination. Namely, cardiovascular deaths.

By so doing, you end up with drug sales of $1.5B/year. Officially classified in pharmaceutical marketing terms as a ‘blockbuster.’

In case you are wondering. I did not choose this paper because it is remarkable, or an outlier of some sort. The only paper, ever, to have manipulated the figures in such a dramatic way. This type of reporting, and the use of combined end-points, has become commonplace. Few notice, fewer care.

I am also sorry to report that I haven’t finished with this paper yet. There are still some very important points that need to be considered. So, until next time, goodbye.

References:

- Misclassification of Myocardial Injury as Myocardial Infarction:

Implications for Assessing Outcomes in Value-Based Programs; JAMA Cardiology, March 17, 2019.

More From This Series

Setting Up The Trick

Research Manipulation Part I

Part 1

Surrogate End-Points

Research Manipulation Part II

Part 2

Deliberate Obfuscation

Research Manipulation Part III

Part 3

Looking Even Closer

Research Manipulation Part V

Part 5

Placebos – The (Not) Nothing Pill

Research Manipulation Part VI

Part 6

If Placebos Are Not True Placebos…Then What

Research Manipulation Part VII

Part 7

Placebos. Trial Blinding, and Biomarkers

Research Manipulation Part VIII

Part 8

The Replication Crisis, And Where Placebos Fit In

Research Manipulation Part IX

Part 9

An Existential Crisis?

Research Manipulation Part X

Part 10

Scottish doctor, author, speaker, sceptic

Support the Broken Science Initiative.

Subscribe today →

recent posts

Journal Club: February 5, 2026

When number-chasing replaces treating the root cause

The iceberg beneath “normal” blood sugar numbers